Leading by Example: Dancer-Director Tamara Rojo Gets Resourceful at English National Ballet

This story originally appeared in the December 2015/January 2016 issue of

Pointe.

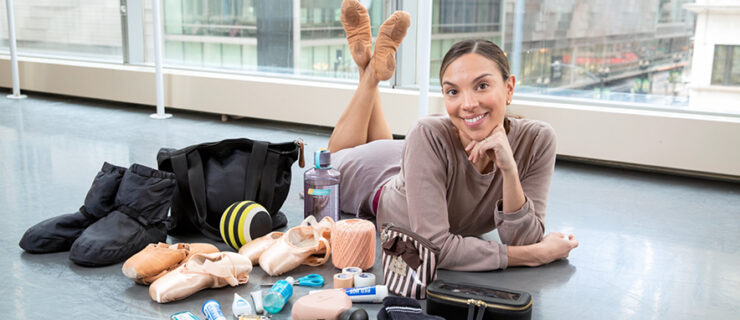

While the 20th century brought a number of high-profile dancing directors, from Rudolf Nureyev in Paris to Mikhail Baryshnikov at American Ballet Theatre, most today don’t juggle the highly demanding tasks of simultaneously performing and managing a company. Tamara Rojo is one prominent exception: The Spanish ballerina left The Royal Ballet to become director of English National Ballet in 2012—and has been leading the company by example ever since.

A dogged multitasker, Rojo wasted no time revamping the company’s image. Often seen as the poor cousin of The Royal Ballet, with limited funding and a mandate to tour widely, ENB struggled to make its presence felt under her predecessor, Wayne Eagling. Rojo has since turned ENB into a resourceful enterprise—from lauded premieres to a new partnership with Sadler’s Wells and plans for a shiny new home—alive with the same energy and individuality she is known for onstage.

One of The Royal’s most recognizable stars in the 2000s, Rojo only realized that she had the desire to direct in her 30s, when Spain’s president asked for her thoughts on the possibility of creating a classical company in her home country. “At the time I felt unprepared,” she says. “I thought: If this responsibility ever comes upon me, I need to be ready, because you don’t always get a second chance.”

Tamara Rojo. Photo by Jeff Gilbert, Courtesy ENB.

Tamara Rojo. Photo by Jeff Gilbert, Courtesy ENB.

Then in her prime, she nonetheless set out to prepare herself methodically in her spare time. In addition to earning a degree in performing arts long distance from Spain’s King Juan Carlos University, she attended rural retreats for dance directors and shadowed National Ballet of Canada artistic director Karen Kain. “She was very generous,” says Rojo. “I’d never had access before to all of the departments of an organization, from box-office to stage management, and she opened them all. It helped me understand what consequences artistic decisions have in practice.”

Rojo applied to another directorship as a practice run, but she had her heart set on ENB, where she had risen to fame as a ballerina from 1997 to 2000 before joining The Royal Ballet. “I loved this company as a dancer. It had lots of limitations, but there was such a family feel, so much talent development.” When the board started contacting potential directors to replace Eagling, she jumped at the chance.

To create the company culture she had in mind, Rojo’s first move was to bring in her own artistic team. In addition to Loipa Araújo, her Cuban associate director, she hired several teachers she knew from her Royal Ballet days. “I needed people who had the skills to coach in the manner I believe in, in a very caring and positive way,” she explains.

The media-savvy ballerina also set out to rebrand ENB. Fashion designer Vivienne Westwood collaborated on a high-end campaign, and while the company’s limited budget means few premieres, Rojo has looked for productions that could “define” ENB as a company: “I wanted both new classics and collaborations with choreographers that were making an impact in the British dance landscape.” Her first project was a new Le Corsaire staged by Anna-Marie Holmes, the first UK production of the ballet. For Lest We Forget, a triple bill of creations to mark the centenary of World War I, she persuaded choreographers Akram Khan, Russell Maliphant and Liam Scarlett to make works.

Rojo with Max Westwell in “Petite Mort.” Photo by ASH, Courtesy ENB.

Rojo with Max Westwell in “Petite Mort.” Photo by ASH, Courtesy ENB.

Three years into the job, Rojo seems on course to secure the company’s future with ambitious moves, including a game-changing partnership with London dance hub Sadler’s Wells. As associate company, ENB will perform twice-yearly seasons at the venue, which will also present this season’s She Said, a triple bill of premieres by women.

Last May, ENB also announced plans to move to state-of-the-art new headquarters in a developing area of East London. The company’s 19th-century Kensington home has only two rehearsal studios. The new building, set to open in 2018, will offer four times more studio space, as well as new training facilities for both ENB and its affiliated school.

While there have been a number of dancer departures since Rojo’s arrival (though roughly as many as in previous years), she didn’t proactively let go of anyone, and instead relies on a mix of role models and young talent. One of her early coups was to bring in Romanian star Alina Cojocaru, who had just left The Royal Ballet; guests like Ivan Vasiliev and Dutch National Ballet’s Isaac Hernández have also brought star power to classical runs. Hernández even joined full-time last April.

With ENB’s extensive touring across the UK and internationally, however, Rojo says there is always space to nurture promising dancers. “You can develop talent very quickly. With so much touring, though, it’s a company that requires a lot of hard work. You don’t find many dancers who think this is a 9-to-5 job—it tends to be a really driven, passionate group.” American corps member Precious Adams is one of the dancers thriving in this demanding environment. She says, “ENB has a strong sense of camaraderie and pride in putting on a good show.” Though she only joined the company in 2014, after graduating from the Bolshoi Ballet Academy, she says that she already feels “like I am a part of the family.”

Rojo with James Streeter in Akram Khan’s “Dust.” Photo by ASH, Courtesy ENB.

Rojo with James Streeter in Akram Khan’s “Dust.” Photo by ASH, Courtesy ENB.

While Rojo, 41, has given up some roles, including Aurora and Juliet, she still dances in most productions, and comes in before everyone each morning to do her fitness training. Administrative tasks are scheduled around company class and rehearsals. “After 35, you don’t waste time; you understand your body. I also believe that as a principal ballerina, you are already leading. How I behave in the studio is already managing others.” For Adams, Rojo is a constant inspiration: “It took me a month to get over the nerves of having my boss dancing next to me. It’s rewarding to have a star to look up to every day.”

Rojo’s biggest challenge as director remains resources, she says. While she has expanded ENB’s development department to improve fundraising, state funding has been at a standstill since she took over, and is going down across all arts organizations in the UK. However, the ballerina-director has proved a passionate advocate for the art form and isn’t one to take no for an answer. “I’m an impatient person, and I stretch ENB to its maximum, in terms of people, space and finances. The company is a cruiser, a tiny boat—change can happen very fast.”

English National Ballet

At a Glance

Number of dancers: 66 + 3 character artists

Length of contract: Year-round

Performances per year: 129 in 2014–15

Website: ballet.org.uk

Audition Advice

ENB doesn’t typically hold auditions. Instead, after a pre-selection based on CV and photos, Rojo invites interested dancers to take class throughout the year. “We say yes to almost everybody, but the rule is that you can only do a maximum of three classes with us,” she says. “A strong technique is important, but I love experience, mature artists who understand their craft.”