António Casalinho and Margarita Fernandes Are Thrilling Audiences at Bayerisches Staatsballett and Beyond

“Perfection!” “Extraordinary!” “Magnífico!”

These comments pepper videos on Instagram featuring Margarita Fernandes and António Casalinho performing the Diana and Actaeon pas de deux at the Prix de Lausanne’s 50th anniversary gala in early February. Yet while the young Portuguese dancers at Germany’s Bayerisches Staatsballett, 18 and 19, respectively, thrill audiences, they’re just as stunned in their own right. The gala in Lausanne featured some of their most admired idols, including Marcelino Sambé, Elisa Badenes and Marcelo Gomes. “It’s really strange to have been a student just a couple of years ago, looking up to these dancers, and now to be sharing the stage with them,” Casalinho says. “It’s hard to believe it’s real.”

The limelight isn’t exactly new to the young pair, who received early recognition from international competitions like Youth America Grand Prix as kids. The Prix de Lausanne, though, holds special significance: After receiving the competition’s top prize in 2021, Casalinho was invited to audition for the Munich-based Bayerisches Staatsballett. Fernandes, then 16, went along so that Casalinho could demonstrate his partnering skills. Both were offered soloist contracts on the spot. Soon afterwards, they left their home studio, the Annarella Sanchez International Conservatory of Ballet and Dance (Sanchez is Fernandes’ mother) in the small Portuguese city of Leiria, where they’d trained together for 10 years, to start their careers.

Beyond their finely tuned technique and a shared appetite for moving big onstage, these young dancers display a clear-eyed confidence more typically found in artists twice their age. A grounded work ethic instilled by their Cuban training centers them, despite their explosive propulsion into the professional ballet world. Moreover, both dancers are masterful actors. “They’ve understood that adopting a certain style, and approaching a certain intent in a role, doesn’t have to compromise their individuality,” says Maina Gielgud, an independent coach who has worked with the pair since before the pandemic. “They really let themselves go there.”

Midway into their second season in Munich, Fernandes and Casalinho, now a first soloist, are settling into professional life. The transition has had its ups and downs, but the pair, who have been dating since 2020, support each other through it all. They’re often cast together, shining in Alexei Ratmansky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, as Franz and Swanilda in Roland Petit’s Coppélia, and as Demetrius and Helena in John Neumeier’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. “They are so talented, smart and theatrical,” says artistic director Laurent Hilaire. “It’s really a joy to work with them.”

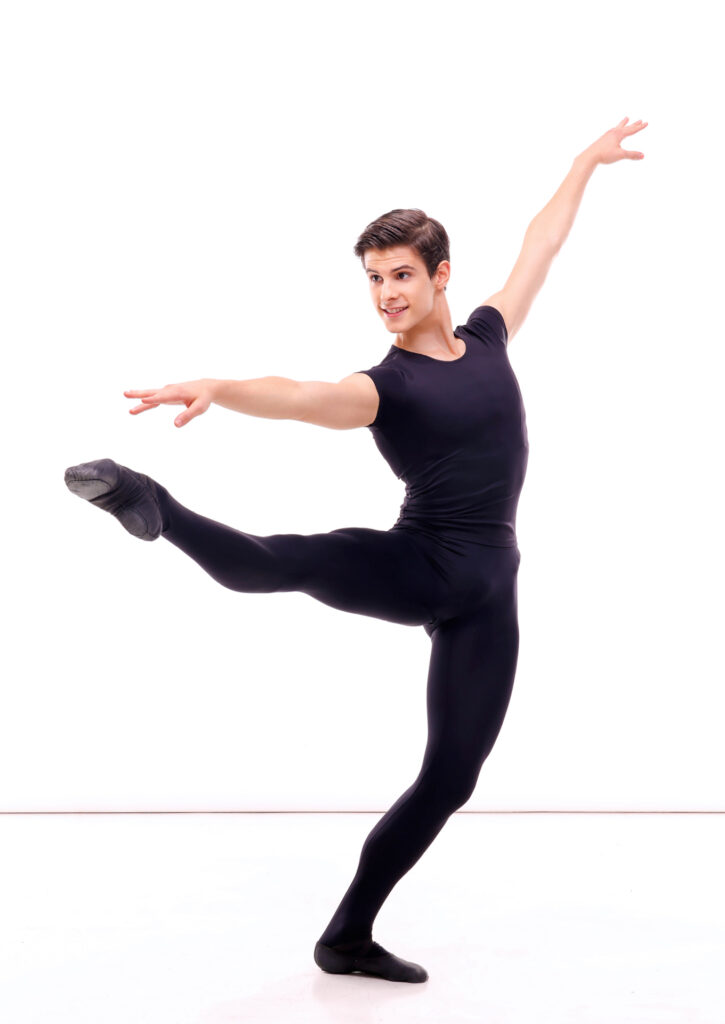

António Casalinho

Casalinho is friendly, down-to-earth and thoughtful. He also has an impish side, which makes him hopelessly likable. He loves Marvel movies, the Eagle’s song “Hotel California,” and his mother’s homemade meals in Leiria. His sense of humor has shown through in roles like Mercutio in John Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet and Puck in John Neumeier’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But it’s his careful dedication and focus on preparation that make his performances truly shine.

George Balanchine’s Jewels was his first production in Munich. Like light bouncing off the facets of a stone, he darted from role to role, dancing the pas de trois in “Emeralds”(alongside Fernandes), the four corpsmen in “Rubies” (he learned and performed all four spots), and the corps of “Diamonds.” He cites a moment in “Diamonds”when he really took stock of his new life. “The theater was so beautiful. I had never danced with a full orchestra before,” he says.

Casalinho went on to be featured in one leading role after another, including Benjamin in Christopher Wheeldon’s Cinderella, Benno in Swan Lake, and a slew of neoclassical soloist roles. “His performances really impress me,” Hilaire says. “Each new opportunity has been the result of what he’s achieved so far.”

It was Casalinho’s friends who convinced him, at age 8, to give ballet at the Annarella Sanchez Conservatory a try. His artistic family (his father is a clarinetist and conductor) supported him from the beginning. “At first I complained that I had to stand at the barre. I wanted to do handstands instead,” he says. But Sanchez guided him to appreciate ballet’s structure and gave a clear idea of the commitment required. Beyond an inquisitive mindset, Casalinho can quickly absorb information. “I’ve always been a fast learner,” he says, “so I could pick up choreography quickly.”

Gielgud confirms this, explaining how impressed she was when she realized the extent of his skill. “We were scheduled to work on Des Grieux’s variation from Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon. I noticed that António had been watching a video before rehearsal, so I asked him to show what he’d picked up so far. I nearly fainted: He performed the entire variation—not just the steps, but the feeling, the style, the acting.”

In Munich, this ability has served Casalinho well. “The company realizes that they can count on you,” he says. But speed also has it downsides, and Casalinho has learned to vouch for himself and his need for rehearsal. “If coaches think that you’re fine without rehearsal, it can be hard to get the time you need,” he says. “The more you work on a role, the more you can develop it.”

A new and thrilling experience has been having choreography created for him. In the December premiere of Alexei Ratmansky’s Tchaikovsky Overtures, Casalinho danced the role of Ariel in the “Tempest” section. The two-minute solo tested his physical and emotional limits. “[Ratmansky] was experimenting, matching what was in his head with the music and trying to squeeze all of that out of me with one technical challenge after another,” he says. “It was amazing to absorb so much artistic energy.” Munich’s artistic staff took notice; on the night of the premiere, Casalinho was promoted to first soloist.

As he rises through the ranks, Casalinho continues to take in his surroundings. He dreams of dancing the “Diamonds” pas de deux one day, roles danced currently by principals Maria Baranova and Julian MacKay. “I learn a lot from watching other dancers. There is so much talent and artistry all around me,” he says. “I want my performances to be memorable. I want the work to pay off.”

Margarita Fernandes

Standing in the wings before her first entrance as Swanilda last season, Fernandes had every reason to be nervous. She hadn’t had any stage rehearsal, and had only found out a few days in advance that she’d be performing the role. But she didn’t have time to be stressed: “I just remember feeling really excited,” she says. Swanilda’s first variation in Petit’s version is tricky, even finishing with fouettés, but Fernandes leaned into her love of acting. Gielgud, who watched from the audience, was impressed. “It was hard to imagine that it was her first time in the role,” she says. “Her natural acting ability stood out throughout.”

While performing might come naturally, transitioning to professional life at 16 years old was not easy. Fernandes first moved into Munich’s school dorms because she was too young to live alone. Skipping the corps de ballet didn’t make life at the studio easy, either. “I didn’t have the chance to bond with the group that the corps usually has,” she says. “I was so much younger than the other women. People were getting engaged and having babies, and I couldn’t really identify with those experiences.” Fernandes became self-critical and overly demanding of herself. “I felt like I needed to constantly prove that I deserved to be a soloist,” she says. “I can tend work too hard, and overdo everything.” Eventually, she learned to stop comparing herself to dancers seven or eight years older than she was, which helped make things easier.

Finishing her high school requirements has also been a balancing act. “I used to be a huge perfectionist in my studies, too,” Fernandes says. “But I had to accept that it just wasn’t possible to give everything to both ballet and school.” When not in the studio or doing homework, Fernandes is reading Harry Potter, visiting Munich’s bustling Marienplatz, or listening to the Portuguese artist António Zambujo’s song “Lote B.”

For Fernandes, leaving ballet school also meant renegotiating her relationship with her mother. “When I was younger, I really didn’t want to hear my mom’s opinion. But at some point, I realized that she is usually right, and we are very close now,” she says. In Munich, without her mom’s daily feedback, Fernandes appreciates her bond with Casalinho, especially when it comes to pre-performance anxiety. “It’s a big help to have someone who knows me so well, who can talk me down in those moments.”

Dramatic roles—and immersing herself in a character—drive Fernandes, and she aspires to perform the major ones, like Juliet, Manon and Odette/Odile. “I don’t think it’s hard to be realistic onstage if you put yourself in the character’s place,” she says. “It’s not facial expressions that are hard to convey. It’s how to walk, how to stand still as that character that takes the work. Nobody tells you how to do those parts of a role—taking time to figure them out for myself makes the role make sense.”

As she and Casalinho begin capturing a worldwide audience, the sky really does seem the limit. Gielgud puts it this way: “Nureyev said: You have to be greedy. You have to be willing to always learn, and to go out and find the possibility in every experience.” And chances to share a laugh have made the ride all the more fun. Case in point: As Swanilda and Franz, the pair had to exit through a door that had gotten jammed shut. “Eventually we tripped through,” Fernandes says, “very awkwardly, as the lights went out. We laughed about it for weeks!”