Dancing With Scoliosis: How I’ve Learned to Work With My Unique Spine

Ballet is a performing art that prides itself on the aesthetics of physical alignment. We train from a young age with the underlying message that our bodies should be symmetrical. But what if your physical stature is inherently out of balance? While almost everybody’s body is asymmetrical in some way, for those of us with scoliosis—a condition I personally experience, in which the spine curves in either a “C” or an “S” shape—dancing can be particularly challenging.

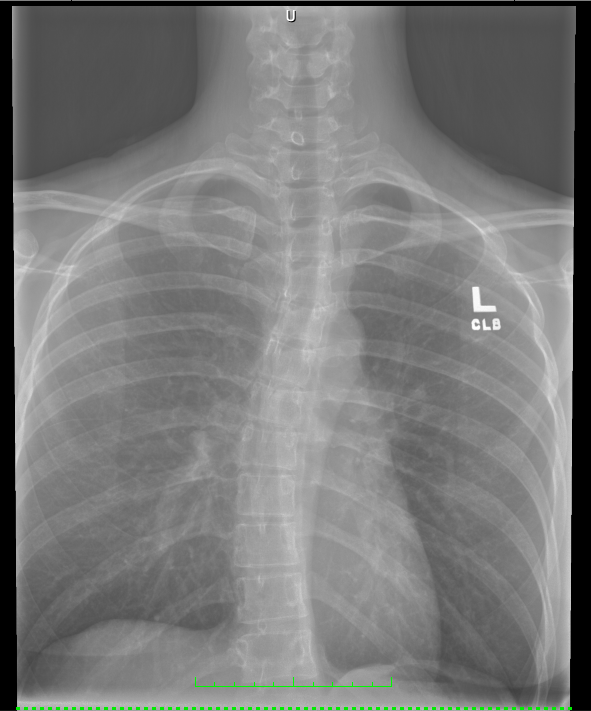

Scoliosis can range from minor to severe, based on the degree of spine curvature, or Cobb angle. A Cobb angle of less than 20 degrees is considered minor, between 25 and 40 degrees moderate, and more than 50 degrees severe. Twisting of the spine is another symptom and greatly impacts the body’s rotation, which can be particularly noticeable in the rib cage. At the least, scoliosis can affect a dancer’s balance and alignment, while at its worst it can impact the organs or require bracing and possibly surgery.

As a young pre-professional student, I didn’t understand the ramifications of this condition on my dancing. I was diagnosed with minor scoliosis at age 13 while being treated fora back injury. My doctors, who regularly treated dancers but were never dancers themselves, weren’t concerned given the slight curvature. However, even slight imbalances are noticeable in ballet and contribute to overall movement patterns.

My ballet teachers didn’t understand the uniqueness of my curved spine. While I was praised for my lines and feet, I was also criticized by instructors who did not understand why I was flaring my ribs or sitting in my hypermobile back (byproducts of my particular anatomy). Rather than offering constructive comments, some treated me as if I was stupid or incompetent. I now know that they didn’t fully understand how to teach dancers with this particular physiology. Corrections that may work for students with a more balanced body won’t always help a dancer with scoliosis.

It wasn’t until recently, as a professional dancer in my mid-20s, that I started to better comprehend my spinal anatomy and use that knowledge to aid my dancing. Weekly sessions of osteopathy (a form of soft-tissue bodywork) from an MD, as well as physical therapy, have helped me understand the three-dimensionality of scoliosis and its trickle-down effect on the rest of the body. My physical therapist specializes in the Schroth Method, specifically created for scoliosis patients. These exercises, which I do daily, combine breath and strength work, while using various props, such as beanbags, to counterbalance the rotation in the spine. It is a multifaceted process that involves considerable visualization, in addition to physical work, to de-rotate the spine across three planes of the body. I also do strength training with a CSCS (certified strength and conditioning specialist) knowledgeable in scoliosis.

With these new approaches I could better correlate what my instructors wanted from the outside to what it felt like for me on the inside. I’d stand in front of a mirror to practice making the connection between what something should look like versus what it feels like, and have since learned how to manipulate my body to get that end result.

Of course, flare-ups inevitably occur. I might experience a stuck feeling in my sacrum and lower pelvis, or a sharp pain in my left rib cage. At their worst, I can barely sleep at night. Visual cues also let me know when I need a tune-up, such as when I’m particularly off-center during balances, or when my posture looks especially slanted. But by addressing my scoliosis on a regular basis through a purposeful wellness plan, such flare-ups occur infrequently.

For those of you with scoliosis, I urge you to commit to scoliosis-specific bodywork and regular strength training, and to seek out specialists in your area with advanced knowledge of this condition, particularly in dancers. Doing so will not only greatly assist you in your dancing, but help you live a healthy, pain-free life as you get older. Even if you’re not currently experiencing pain or other challenges, the earlier you can address scoliosis symptoms the better—they can increase over time, and it’s best to start tackling them while you’re still growing. Also, train with teachers who provide individual attention, truly taking into account each student’s physiological differences. The reality is there is no one-size-fits-all way to teach ballet.

But, mostly, I want to tell aspiring dancers not to be deterred by their scoliosis. Plenty of dancers with this condition have enjoyed successful careers. You just need to put in extra time and effort to address your unique spine. With the right support and personal understanding, dancers with scoliosis are fully capable of flourishing.