Summer Study Rejection: Dealing With the Disappointment of the Thin Envelope

This story originally appeared in the December 2010/January 2011 issue of Pointe.

As a young student at a small ballet school in upstate New York, I was obsessed with getting into the School of American Ballet. From the age of 10, I entered class each day with the ultimate goal of studying at SAB dangling before me like a carrot on a stick. Every effort I made, every extra class I took was for the sole purpose of getting into what I thought was the only ballet school that really mattered.

I auditioned for SAB’s summer program for the first time when I was 12. In the weeks that followed, I became a vulture hovering over my family’s mail, squawking at my mother if the day’s letters were not presented for my inspection when I walked through the door. The day the letter finally arrived, it was thin and limp. I cried for a week as I dealt with the crushing feeling of rejection for one of the first times in my life.

My mind filled with questions and self-doubt. What was wrong with me? Why wasn’t I good enough? I figured I must be too fat, too slow, my feet too flat. I had worked so hard. I had wished on every fallen eyelash and dead dandelion in pursuit of my single goal, just to have a three-paragraph form letter conclude that I was a failure. For a while, I let myself wallow in the comfort of my resentment, content to believe that success should have come easily, and that to fall was the same as to fail.

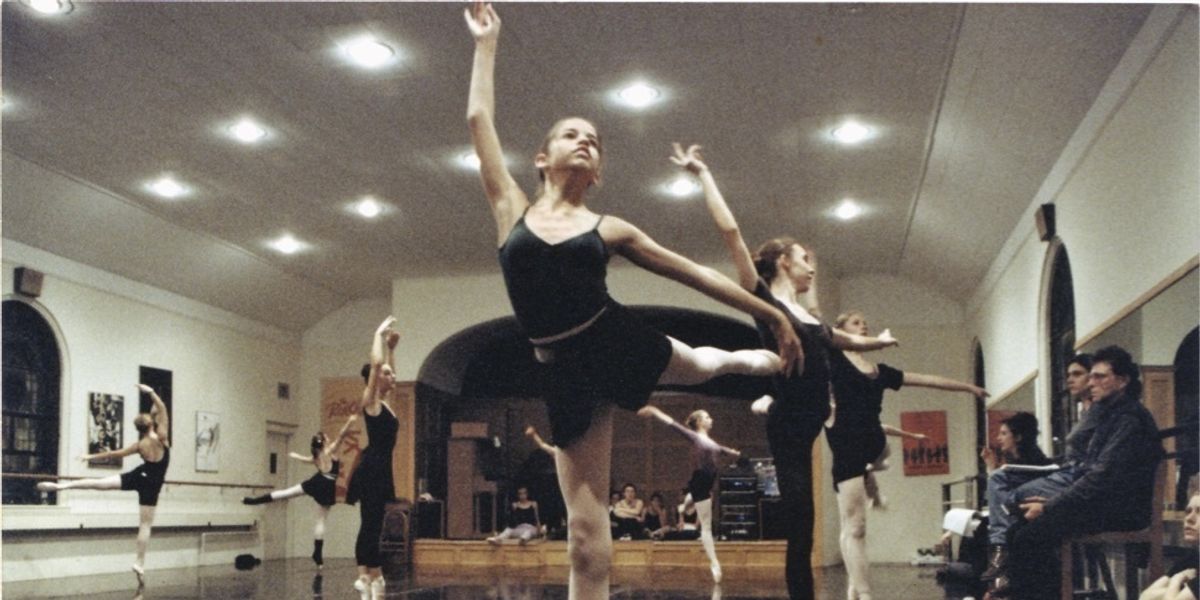

But my parents and teachers encouraged me not to give up, to pour my emotion into my dancing. Eventually, my self-pity transformed into a focused rage, and I began to approach ballet with new seriousness. Even though it wasn’t SAB, that summer I had gotten into Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School’s intensive and decided to go. There I found teachers who believed in my potential and wanted to work with me. I began to realize that I wasn’t as strong as many of my peers who had come from more rigorous programs. I studied the girls in the advanced level every chance I got and tried to mimic their movements, their grace. I took classes like Pilates and yoga for the first time, gaining strength in my core. At the end of the day I would collapse onto my hard twin bed exhausted and inspired.

I attended the PBTS program the following summer as well, and was asked to stay for the year-round program during my freshman year of high school. Initially, I struggled to keep up with my classmates, again reminded that I was still much weaker technically. But I was determined to catch up. I took extra classes in lower levels the entire year to speed up my improvement. My focus shifted from an obsession with taking class at SAB’s Lincoln Center studios to the greater goal of being my absolute best.

McGuire’s first arabesque audition photo from age 15, the year she got into SAB. Courtesy McGuire.

McGuire’s first arabesque audition photo from age 15, the year she got into SAB. Courtesy McGuire.

And it paid off. The next summer I got into SAB’s summer intensive and was even placed in a high level. I wish I could say that this was the end, that every moment after yielded success and opportunity because I had weathered that early disappointment so well. But unfortunately, dealing with rejection may as well be part of a professional ballet dancer’s job description, no matter how good you are. You get into the great school, but not the level you want. You’re cast as an understudy for the part you know you deserve. You don’t get a job with the company you want, or worse, you lose your job with the company you love. The most important lesson to be learned from any one rejection is how to better deal with the next one.

Auditioning for summer programs will always be particularly hard. It’s often a dancer’s first barometer of where she stands in the highly competitive world of ballet, and no one wants to hear that they aren’t quite there yet. Rejection can be the truest test of a young dancer’s potential, not because you weren’t accepted, but because it is a demonstration of your ability to rally back in pursuit of your dream. Instead of allowing the disappointment to take the wind out of your sails, remember that there are things to be learned by not getting the thick, glossy packet every time you try. Believe in yourself enough to see the turndown for what it really is: the opportunity to prove them wrong.

Advice From Auditioners

Don’t Overthink It

Dancers often put far too much weight on external factors when auditioning. They think, “If I audition too early or late in a particular school’s tour, I’ll be less likely to get in,” or “If I go to one city to audition, I’ll have better odds than at another.” Denise Bolstad, administrative director for Pacific Northwest Ballet School, says that these preoccupations are a waste of time. “We don’t have a quota of students that we’re looking for,” she says. “We take whomever we feel will benefit from the program. We try to be objective and fair, whether it’s the first audition or the last.”

It’s All In The Eye Of The Beholder

Where you want to be may not be the same as where you should be. Ethan Stiefel, dean of the dance program at University of North Carolina School of the Arts, urges disappointed applicants to remember that dance is a subjective art. “Potential in one person’s eye is not the same as in another’s,” he says.

They Want You To Succeed

Ultimately, the director of any program is looking for students who will flourish within their particular summer course. No one wants to put a student into

a situation where they will become frustrated and discouraged. According to Sharon Story, director of The Centre for Dance Education at Atlanta Ballet, this is considered in level placement as well. “We’re pretty conservative on our first placement because it’s easier to move students up than down,” she says. “We try to place them where they’ll succeed.”

A Lot Can Change In A Year

A young dancer’s facility, strength and technique are everchanging. Bolstad points out that for dancers as old as 14, a rejection is often just an issue of physical strength. “Because we’re dealing with young adults, a great deal can change over the course of just six months,” says Stiefel. “I would encourage a student who’s been rejected to work hard and re-audition the following year, because they may have made huge leaps and bounds.”