From Paris With Love: Mathilde Froustey Captivates at San Francisco Ballet

This is Pointe’s April/May 2014 Cover Story.

This past January, a standing ovation greeted San Francisco Ballet’s newest Giselle, Mathilde Froustey, when she took her bows. As she made her debut in the ultimate French Romantic ballet, the former Paris Opéra Ballet sujet (demi-soloist) was a long way from the Palais Garnier. Months before, Froustey, 28, had made waves by announcing she was taking a year’s leave from the POB to join San Francisco Ballet as a principal—the first high-profile transfer from the insular French institution in years. With only two weeks of rehearsals, Giselle should have been a daunting experience, but Froustey gave a heartfelt, accomplished performance. “There was no time to be scared, to have doubts,” she says. “I found my place as a principal. In Paris, I never thought I’d do the ballet.”

Froustey had other opportunities to show her mettle with the POB, however, where she hovered on the brink of a breakthrough for years. In December 2012, when the slender brunette made her Don Quixote debut, she was the Kitri everyone scrambled to see, claiming the stage with her customary blend of elegance, lightness and spontaneity. Her performance might have seemed to warrant a promotion to soloist, but none was forthcoming. A decade after she joined the company and won a gold medal at the International Ballet Competition—Varna, and seven years after her promotion to sujet, Froustey remained at the upper corps rank, in spite of the ovations she garnered in leading roles. A month before Don Quixote, she had tried her luck again at the concours de promotion, the annual internal competition where the fate of all lower-ranked POB dancers is decided by a jury composed of artistic staff, company members and guests, and experience often counts for little. She failed yet again to win over judges, and since the vote is secret, received no explanation. In San Francisco, Froustey is the newest member of a long line of French dancers, among them Muriel Maffre, Sofiane Sylve and Pascal Molat, nurtured by artistic director Helgi Tomasson. His gamble on Froustey seems to have paid off: In SFB’s faster-paced environment, a star has finally spread her wings.

Born near Biarritz, a short ride away from the Spanish border, Froustey was a hyperactive child. Her mother signed her up for ballet classes to improve her posture. “I was a tomboy, so it was torture for the first three years,” she says with a laugh. “But one day I decided to apply myself, and I realized it wasn’t so bad.” Froustey set her sights on becoming a dancer, enrolling at Marseille’s Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Danse and going to dangerous lengths to improve her feet’s flexibility with weights and furniture when she was told they were ill-suited to ballet.

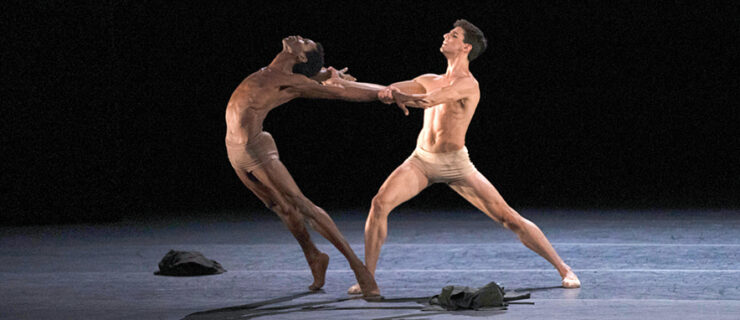

Froustey in a gala performance from “Giselle’s” Act II. Photo Courtesy Froustey.

Froustey in a gala performance from “Giselle’s” Act II. Photo Courtesy Froustey.

The Paris Opéra Ballet School initially rejected her, deeming her Achilles tendons too short, but when she was 14, her mother sent photos again. Froustey was accepted as a paying student (the school is tuition-free for students admitted at a younger age), and spent three unhappy years there: “I was coming from a fun, relaxed environment, and I didn’t understand why everyone was so mean. At 14, you shouldn’t be told that you’re fat and kicked out of class.”

She found solace in weekend classes outside the school with Attilio Labis, a former POB étoile and renowned teacher, and the POB jury tasked with picking students for the company saw her potential. Joining the company in 2002 was “liberating,” she says, and once there, her rise to the top seemed inevitable. Blessed with a sparkling technique and unmistakable personality onstage, Froustey caught the eye of former Bolshoi director Yuri Grigorovich when he came to set his Ivan the Terrible. He cast her in the leading role of Anastasia when she was just a second-year corps member, a rare honor in the strictly hierarchical POB. In 2004, her gold medal at Varna was the first awarded to a French dancer since Aurélie Dupont a decade earlier.

Froustey was appointed sujet in 2005 and classical leads followed, including Swanilda in Coppélia, Lise in La Fille mal gardée, Gamzatti in La Bayadère and Clara in Rudolf Nureyev’s Nutcracker. The arcane concours soon became her nemesis, however. Repeatedly passed over, she started to doubt her abilities. “I don’t dance well during the concours; I’m very nervous. I tried everything: hypnosis, mental coaching, even chocolate. Every year, around the time of the concours, I had a principal role. I did a stage rehearsal as Kitri the day after competing, and I didn’t even rank among the top six.”

At POB, Froustey alternated between leads like Kitri and corps work. Photo Courtesy Froustey.

At POB, Froustey alternated between leads like Kitri and corps work. Photo Courtesy Froustey.

Not even her artistic director, Brigitte Lefèvre, could tell her why the jury consistently didn’t vote for her. Some ventured that her style was too extroverted and virtuosic for Paris, where restraint and purity are valued above all; Froustey was also considered to be part of a “lost generation” of very talented sujets held back by a lack of available soloist positions.

She tried not to dwell on the situation, however, and took advantage of numerous invitations to guest abroad alongside stars in galas from New York to Moscow, where she was often mistaken for a full-fledged principal. A temporary move abroad to experience different styles had been on Froustey’s mind for some time. Moving back and forth between principal and corps work was becoming harder on her body, but Don Quixote was a turning point. “It was my first three-act ballet and my dream role. Afterwards it was very hard, both psychologically and physically, to return to the corps, and there was no guarantee I would ever dance Kitri again. I had to do something, because I didn’t want to be bitter.”

A few weeks later, she sent a prospective e-mail to San Francisco Ballet. She found the company’s repertoire and style more familiar than that of some other leading U.S. companies. Tomasson remembered Froustey from Paris trips, had a look at videos she sent and, in an unusual move, offered her a principal contract over the phone a few days later. “I saw someone who deserved it, who had worked for it, and I thought it would give her confidence in herself,” he says. “There was no question in my mind that she was excellent.”

Froustey had to pinch herself when she hung up. Last July, she went straight from her final Paris performances in La Sylphide to the start of the season in San Francisco. The transition was far from easy, however, as she struggled to find an apartment and her place in the company. “I had to learn everything from scratch. I felt like people didn’t find me that impressive for a new principal, and I kept thinking, ‘I’m not as flexible as the Russians, I don’t turn as well as the Cubans—what do I have to bring?’ ”

The many French speakers at SFB helped with the practicalities, however, and away from the sheltered environment of the Paris Opéra, where dancers are civil servants with lifetime contracts and retire on a pension when they turn 42, Froustey quickly learned to be more independent. “You have to be proactive here,” she says. “People dance fast, learn fast, go onstage without as many rehearsals. In Paris, we were a little cosseted.” Onstage, everything fell into place, with acclaimed debuts during the company’s New York tour last fall, in Tomasson’s Nutcracker and in Giselle. “She lights up the stage,” says Tomasson. “What I love about her dancing is her joy. She feels music, and as an audience member, you connect with her. She’s made to be onstage.”

And while the pace has pushed Froustey, a self-proclaimed “slow learner,” out of her comfort zone, she relishes the excitement that comes with it. “I’m rediscovering the pleasure you get from taking risks onstage. In Paris, there was no way you’d be allowed to change a step, but here you can work out your own Giselle. You’re more of an adult in your work.”

Homesickness remains a challenge, but Froustey credits Maria Kochetkova, now a friend, with helping her in and out of the studio: In December, they spent a few hours alone ironing out the details of Froustey’s Nutcracker variation. Froustey’s boyfriend, filmmaker Charles Redon, followed her to San Francisco and is making a documentary about her American year.

Her season will end on familiar ground with San Francisco Ballet’s Paris tour in July. Before that, however, Froustey has a momentous decision to make: stay in California and relinquish her POB position for good, since dancers are only allowed one year’s leave, or return to the corps in Paris. “I miss Garnier so much, it’s my home, and it breaks my heart to think I’d never dance on that stage again,” she says with a sigh. “But I want to dance. I want to feel like an artist.”