Michaela DePrince Makes Her Next Move

Michaela DePrince surprised the dance industry in September when she announced that she was joining Boston Ballet as a second soloist. Since 2013 she had been ensconced at Dutch National Ballet, where she quickly rose to soloist in 2016. But over the last four years, she has also endured a multitude of challenges in body, mind and spirit.

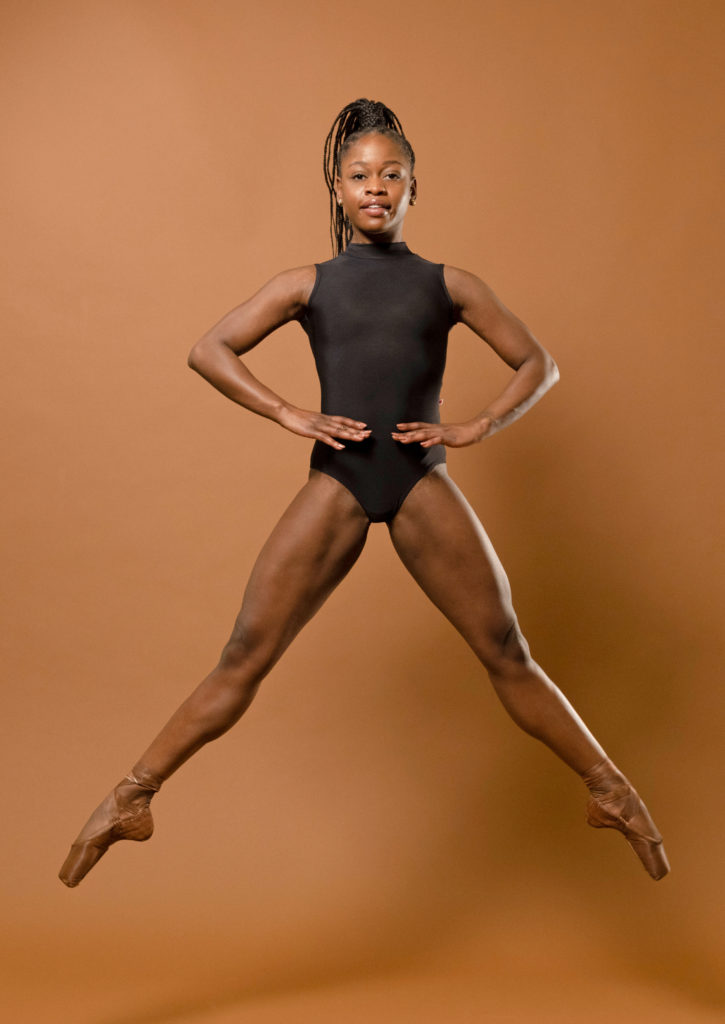

DePrince’s beautiful complexity as both a woman and a ballerina is almost impossible to capture in words. She defied the odds she was born into as an orphaned child survivor of the Sierra Leonean Civil War (DePrince was adopted by American parents), as well as the art form she chose. She managed to not merely navigate them both, but excel beyond measure. The petite 26-year-old leaves an impact wherever she stands, be it on an opera house stage, on a film or television screen, or as a speaker, activist or influencer.

Her life in Amsterdam was big—huge, actually. Not only was she a soloist with DNB, she was an international star with endorsements, engagements, books and movies, complete with worldwide jet-setting. DePrince served as ambassador of War Child Holland; in 2019, she produced a gala that raised over a half-million dollars for the organization, which provides support for children and young people affected by armed conflict and war.

She seemed to be everywhere at once. “I would be doing music videos, I’d be performing principal roles, [giving] speeches,” says DePrince during a recent interview over Zoom. “And it just became kind of a lot.”

The pressure to be perfect took its toll. “When I would be doing too much, I felt like a fraud, like I wasn’t fully there,” she says. “And I wasn’t fully committed, because I was being pulled in so many directions. Over the past few years, I have been trying to slow down.”

Today she is seeking home, both personally and professionally, and Boston Ballet feels to her like a good place to nest.

A Challenging Four Years

In 2017, a ruptured Achilles tendon set a cascading effect in motion that would lead DePrince to make self-care a priority. Not only did the injury literally sit her down for a while, in that stillness she was forced to confront demons from the past. Later that year she went public about seeking therapy to address the post-traumatic stress disorder from her childhood in Sierra Leone.

DePrince has long struggled with recurring nightmares, which cause insomnia. Ironically the retelling of her story, while inspirational to many, has kept her bound to the trauma, reliving it with every recounting. Without a full-time dance schedule, there was space for her to sit with herself, which led her to seek help. “If I hadn’t ruptured my Achilles, I don’t think I would have had the time and space to be able to know how important my mental health was.”

The next two years were fraught with physical setbacks that prevented DePrince from returning fully to the stage. At the same time, her adoptive father Charles DePrince’s health was in rapid decline due to Parkinson’s disease. In June 2020, he passed away.

“That was really hard for me to deal with, because I couldn’t say goodbye,” says DePrince, who was stuck in Amsterdam. COVID-19 travel restrictions and the often volatile situation on the ground with Black Lives Matter protests made it difficult and possibly dangerous for her to get to Atlanta, where her family is based. “I tried everything,” she says, adding, “a Black female all by myself in quarantine for two weeks, alone… It just wasn’t safe enough.”

Her father’s death left her unmoored. In September 2020, she announced that she was taking a leave of absence from DNB to deal with the loss, and to focus on healing through therapy.

“I didn’t think I was going to be able to come back,” says DePrince, adding that her Achilles injury caused a crisis of confidence, and a loss of identity. “People kept reminding me what I was. And I’m not that anymore. I’m a completely different artist.”

Healing Body and Mind

The hiatus allowed DePrince to truly assess what was important to her. She came to a couple of realizations: The first was that dancing was her heart and soul. “I was trying to figure out a way to get the love back, not just for being in the studio, but really being there for me and not for others,” says DePrince.

The second was that it was time to move on from DNB. “This is such a short career. I felt like it’s time for me to go somewhere else to continue to grow, have a different repertoire, meet different dancers and feel like I’m getting fed.” Leaving the company was a decision she made solely for herself—and without an exit strategy.

During this time she turned to her longtime mentor, renowned ballet coach and Juilliard faculty member Charla Genn. (She and Genn met when she was 15 during a guest appearance with South African Ballet Theatre, now Joburg Ballet). The two began regular Zoom coaching sessions. “We completely retrained her upper back, her port de bras, her alignment,” says Genn. “We found the weaknesses in her body and we strengthened it. She’s functioning very well [now]. She’s on pointe with ease, and her jump is back to where it was.”

Genn has also been instrumental in DePrince’s healing, beyond the instrument of her body. “She cares about me as a human and not about me as, ‘Oh, I’m going to make her a star and have my name attached to it,’” says DePrince. “I have to say, from my experience, that it has been very rare to have.”

Jobless, DePrince sought her advice. Genn consulted with fellow coach Hilary Cartwright, who suggested Boston Ballet. After doing some research, DePrince was drawn to both the dancers (having worked with Chrystyn Fentroy at Dance Theatre of Harlem) and the repertoire. She also appreciated the fact that Boston Ballet is 15 percent Black dancers (including soloists Fentroy, Lawrence Rines and Irlan Silva and artists Daniel Randall Durrett, My’Kal Stromile and Tyson Ali Clark).

Cartwright called Boston Ballet’s artistic director, Mikko Nissinen, and asked if he had open positions and was interested in a conversation with DePrince. “I said of course,” says Nissinen. After speaking with DePrince multiple times and viewing her reel (pandemic restrictions prevented her from auditioning in person), Nissinen reached out to his former partner and current DNB ballet master Caroline Sayo Iura. “She had sort of been like her mentor there,” Nissinen says. “So she knew her very well and loved her and was able to give me insight.”

A New Home

During DePrince and Nissinen’s talks, company culture was one of the topics of conversation. “This is a company that is a team effort,” says Nissinen. “It’s about the whole company doing well. I care about every single person here. The staff is very supportive, and naturally we have expectations of a very high standard.” His perspective resonated with DePrince. “It’s not about being a people pleaser,” she says. “It’s about also having a good career and enjoying it, as both a human being and as an artist.”

Being fully seen and considered is important to DePrince, as well as being able to bring the full spectrum of her being into the studio or onstage. That includes the complexity of her Blackness (as an African raised in America), her hair (she is wearing braids now), her espresso hue (wearing tools of her trade that reflect that) and, most importantly, her mental health.

“I felt that I was being embraced for who I am and what I stand for,” says DePrince. “I feel that if I want to wear brown tights, it’s not going to be an issue.” She adds that she feels safe at Boston Ballet thus far. “I came in here feeling like, ‘This is me, and I hope you accept it.’ And so far people have accepted it.”

In September, at the company’s annual meeting, DePrince performed a solo choreographed by Peter Leung, a frequent collaborator. It was the first time Nissinen saw her perform live. “It was awesome. It was great to see the artistry, her confidence and how she translated in live performance.”

DePrince understands the power and reach of her platform. “Hopefully, dancers around the world can continue to just be who they are as human beings and as artists.” She has an overwhelming need to make the world a better place, she says. By using her visibility to highlight the importance of mental and emotional health, the recognition of the humanity of the artist, and self-care, she is the type of “influencer” ballet culture and artists need today.