Nicole Cuffy Couldn’t Find the Type of Ballet-World Story She Wanted to Read—So She Wrote It

Writer Nicole Cuffy has always felt connected to ballet. She’s danced since childhood and is a regular at the theater. But when she first began reading fiction about the art form, she couldn’t find a story with the nuances and characters she longed for.

“A lot of the books at the time were either this overdramatized version of ballet, where you have these dancers pitted against each other and putting glass in each other’s pointe shoes,” she says. “And then on the other end of the spectrum you had ballet books that were good, valuable stuff, but didn’t have any Black dancers, especially not any Black female dancers.”

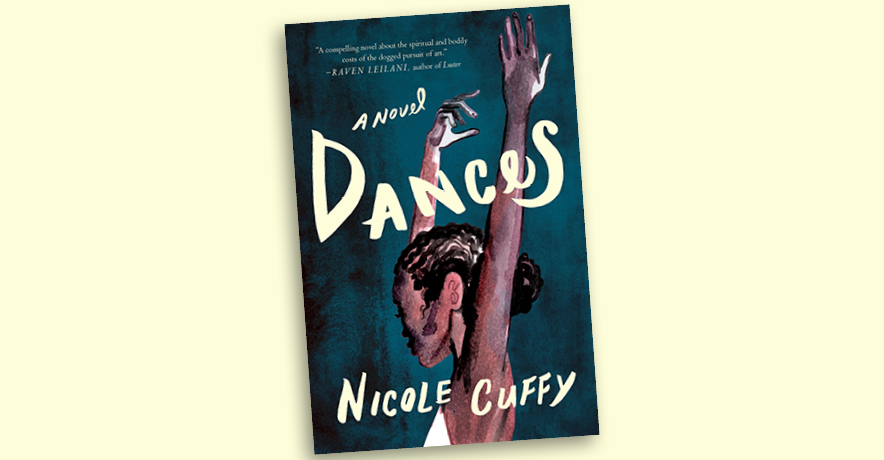

Cuffy’s debut novel, Dances, out May 16, is the story she wishes she’d had. The book follows Cece Cordell, the first Black principal dancer at a fictionalized version of the New York City Ballet, as she navigates her newfound fame and processes the addiction struggles and subsequent disappearance of her older brother, Paul, who supported her dance dreams from the beginning. Pointe spoke with Cuffy about the book.

Tell us about the writing process for Dances. How did the story evolve as you worked?

I remember the specific moment when I realized I was going to have to write this story myself—I was in the bath, which is part of my nightly ritual and I often get ideas in the tub. It was probably April or May of 2015 and I was like, “Okay, I’m not finding the kind of ballet story that I want to read or that I have a craving for in fiction right now, so I’m going to have to write it.”

I started thinking about what the story would look like, and I wanted to write about the first Black female dancer to be promoted to the level of principal at American Ballet Theatre. The problem was that just a few months later, Misty Copeland became the first Black female dancer to be promoted to principal dancer at American Ballet Theatre. Her promotion was so momentous that it would have been a lot to ask the reader to suspend disbelief for me to write a book about a Black ballerina at ABT that completely ignored Misty Copeland.

So I abandoned the idea for a while. I didn’t really revisit it again until about 2016, when it suddenly occurred to me, “You idiot, you can just set it at another company!”

Your protagonist, Cece Cordell, has such vibrancy and nuance. How did you develop her character?

She mainly came out of what kind of Black dancer I wanted to read about. There were a couple things, as I was sketching out this character, that were important to me in terms of taking on the responsibility of writing about a Black female dancer in a market that didn’t really have anything like it yet. I wanted her to be immersed in Blackness, culturally, which is why I set her in Brooklyn, in a Black community.

It was important to me for her mother to be very Black-identified and for her brother to also be very Black-identified, in different ways. Paul represents a more colloquial Blackness, whereas her mother is more interested in offshoots of Black nationalist identity. And then Cece is trying to find her comfort level of expressing her own Blackness in a world that is predominantly white.

It was also really important to me that she wasn’t a type of Black that was proximal to white in a way that would make classical and neoclassical ballet audiences comfortable. I very intentionally mentioned her hair texture in the book as being kinky. She has 4C hair—it’s not loose. And she’s dark-skinned, she’s not light-skinned or mixed. That was because I wanted this character to further push the conversation that I think is already happening in the real world of ballet, where we’re starting to have more frank conversations about race. But the pace, in my opinion, has been pretty slow.

Your book touches on quite a few real-world issues, like ballet’s diversity problem as well as the lack of agency dancers sometimes feel when it comes to choreographic and artistic decisions. How did you research these themes to portray them accurately?

I knew what the conversations happening within ballet were, in relation to race and representation, and in particular—I keep specifying—in classical and neoclassical ballet, because that has been the genre of dance that I feel has been the slowest to catch up. I was keenly interested in those conversations as a Black woman myself, who is a lover of dance and who can also recognize some of the racist origins of certain ballets. But what I didn’t necessarily have as much of an ear to was how the actual dancers felt, in an unfiltered way.

I was interested not only in how dancers of color felt, but I also wanted to know to what extent white dancers were aware of it and how passionate they were about it. I sought a lot of interviews, read everything I could get my hands on that came from Black dancers who were no longer dancing and maybe were dancing at a time when ballet was even more hostile to Black bodies, in particular Black female bodies, than it is now.