The Boy From Kyiv Explores the Life and Art of Alexei Ratmansky

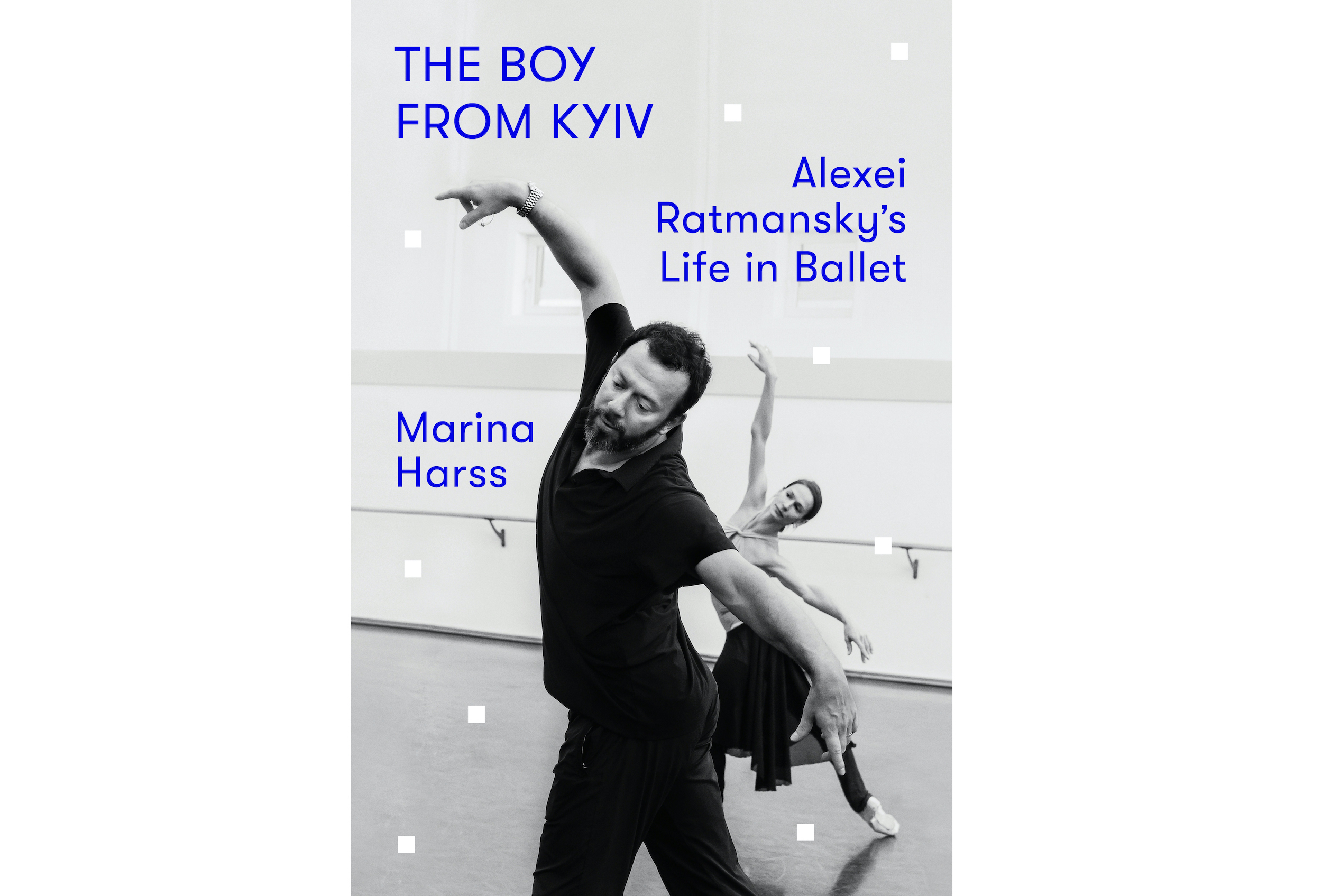

Globetrotting choreographer Alexei Ratmansky is a peculiarly 21st-century figure. Having served as artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet, and then artist in residence first at American Ballet Theatre and now New York City Ballet, he embodies geopolitics in a shrinking and more fractured world. Marina Harss’ terrific biography, The Boy from Kyiv: Alexei Ratmansky’s Life in Ballet ($35, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), delivers a thorough take on the man and his prodigious output.

The child of a Russian mother and a Ukrainian father, Ratmansky spent his early years in Kyiv before enrolling at age 10 in the Moscow State Academy of Choreography, associated with the Bolshoi Ballet, 13 hours by train from his home.

When he arrived in Moscow, Ratmansky had never taken a ballet lesson; he was admitted on his physique. The year was 1978, and his parents decided that such a prestigious school would lead to professional opportunities and a good career. That was understatement. The details on Ratmansky’s ballet training are reason enough to read this book—the range of classes would make any dance artist jealous.

Ratmansky’s mother’s best friend from childhood, Lia, and her husband, lived in Moscow and cared for young Alexei. Lia had “big ambitions” for her charge, writes Harss, “even more than [his parents] did.” She gave Ratmansky a deep and wide cultural education, teaching him English (indispensable once he launched). He worked hard and began to think like a choreographer, organizing dances among close friends. He took these dance creations seriously; “he already saw himself as a director,” Harss writes. By the time he graduated, Ratmansky was more well-rounded and worldly than his classmates.

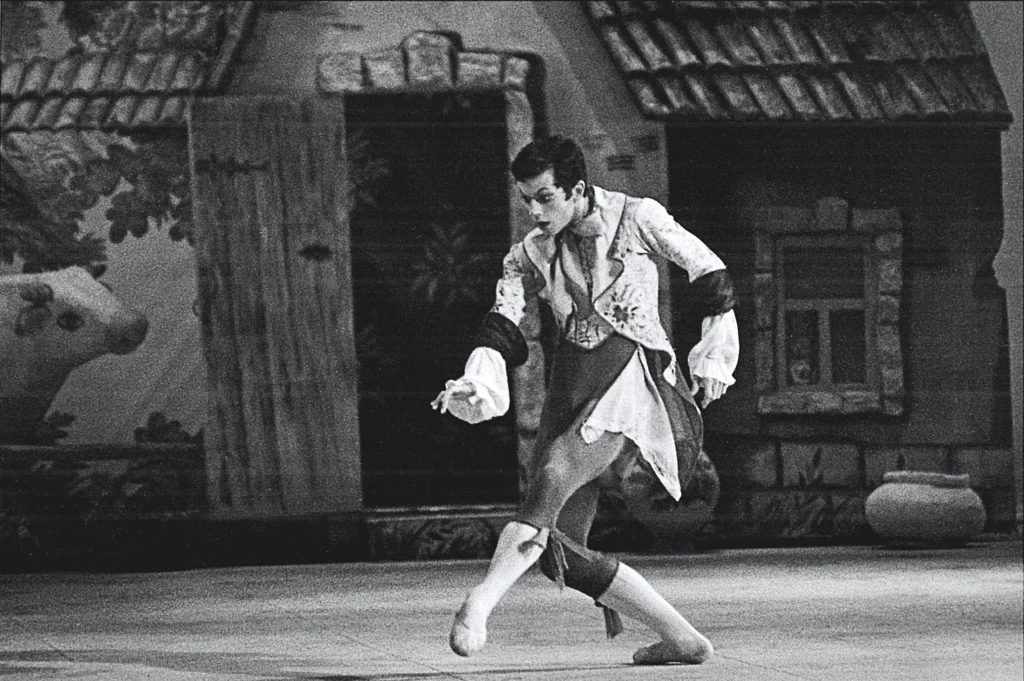

It seemed that Ratmansky would settle into a comfortable career at the National Ballet of Ukraine, where he danced “from the beginning of perestroika to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.” Ratmansky expanded his vistas by touring with the company to Japan, western Europe, Mexico, and Canada. No longer cut off from Western repertoire, he soaked up as much international choreography as he could. He started creating dances, too, mostly solos and duets for ballet competitions.

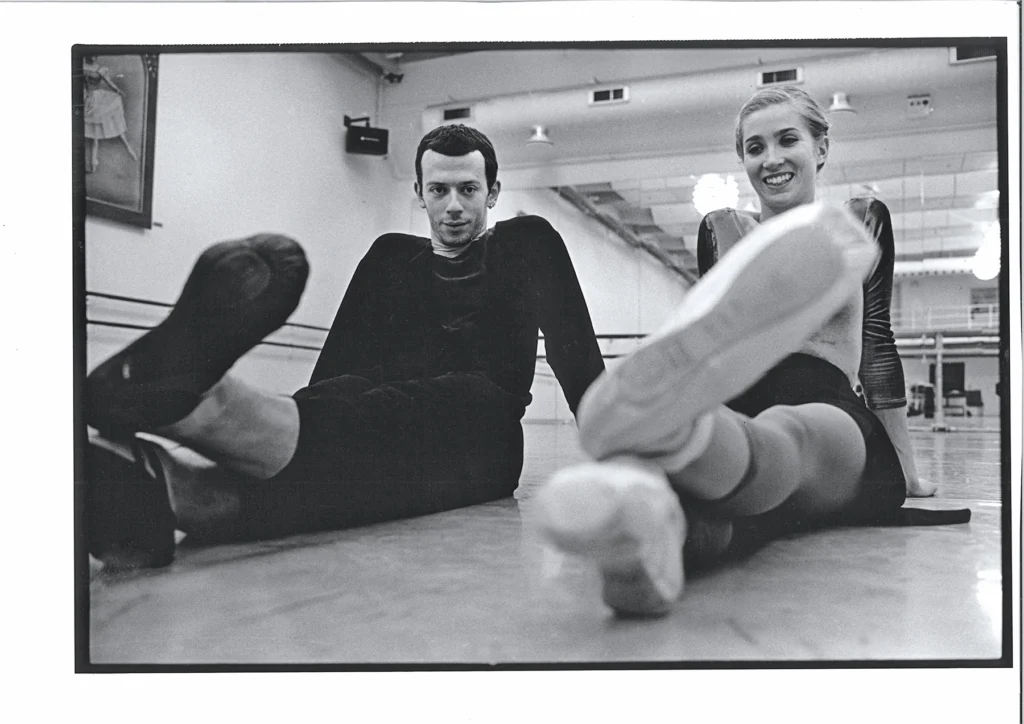

He also met his wife in Kyiv, fellow dancer Tatiana Kilivniuk, a Ukrainian who shared his love of travel. Eventually, Ratmansky landed a job in the Royal Winnipeg Ballet in 1992. Tatiana would join a year later.

In Canada, Ratmansky began in earnest his study of Western ballet, music, style, and culture. He entered more choreographic workshops and competitions and was invited to stage an evening of his work at the National Ballet of Ukraine. After Winnipeg came freelancing across the former Soviet Union, followed by a prolonged stint with the Royal Danish Ballet, where he immersed himself in the Bournonville style and, again, soaked up what he could. In addition to Balanchine, he danced in works by John Neumeier and Maurice Bejart, but was disappointed not to be cast in William Forsythe’s ballets. Alexei and Tatiana’s son, Vasily, was born in Copenhagen, and life was comfortable, although he and Tatiana felt underused as dancers.

Meanwhile, in Russia, Ratmansky was becoming known as a choreographer. During his freelancing years he had begun a fruitful partnership with Nina Ananiashvili. In 1998, he choreographed the Japanese kabuki-inspired Dreams of Japan for her touring ensemble. Ratmansky’s wide-ranging imagination was on display, with a score by the Japanese drumming group Kodo learned at pains by the Bolshoi’s percussion section. The ballet was an instant hit and a turning point.

More commissions came, and world travels increased his visibility. He was invited to create a full-length Cinderella for the Mariinsky Ballet in 2002. From there he went to New York City at Peter Martins’ behest to participate in NYCB’s Choreographic Institute. In 2003, the Bolshoi premiered one of his most famous ballets, The Bright Stream.

In 2004 Ratmansky was named artistic director of the Bolshoi. The book gives marvelous details of this fruitful but increasingly fraught time in his career. Ratmansky was looking to New York by 2008, and mounted Concerto DSCH at NYCB to a “thunderous reception.” Harss details how his artist-in-residence negotiations with NYCB fell through, exacerbated by an overeager interview in The New York Times. A few days later, Ratmansky would be offered the same position at ABT; artistic director Kevin McKenzie had seized the opportunity.

Ratmansky has been encircling the globe ever since, reading, listening to new music, exploring his Jewish heritage, and creating. He’s forged opportunity through hard work, drive, skill in language, persistence, and, of course, imagination. I found it notable that a number of his ballets opened to mediocre reviews, which neither slowed his career nor dampened his creativity. And Harss does not shy away from discussing his more controversial moments, such as his social media post claiming “There is no such thing as equality in ballet”—tin-eared from a man known for politeness.

The book ends with Ratmansky’s declaration of support for Ukraine and painful separation from his loved ones there, to say nothing of the destruction of the war. In an ironic twist, he has since left ABT to become an artist in residence at NYCB.

With choice photographs and extensive endnotes, Harss does an elegant job of introducing this quiet man with a big career. Her book takes a fascinating journey with Ratmansky against his place in history. Readers watch him till new ground, taking the world stage through determination, drive, and a capacious imagination.