A Brief History of Tutus, From the Romantic Era to Today

The tutu has become the symbol of the ballerina. But what is the history of this strange protruding skirt which allegedly gets its name from the French children’s word cucu, meaning “bottom”? Pointe took a look back at some important moments in innovation.

The Romantic Tutu

In 1832 the ballet La Sylphide premiered in Paris with ballerina Marie Taglioni in the title role. This work sparked the Romantic era of ballet, and Taglioni’s dress of a white bodice and bell-shaped skirt instantly became the model costume for a ballerina.

Tutus were strongly influenced by current fashion and the advances of the Industrial Revolution. They were made from cotton muslin and gauze, which had previously only been available from India but was now being grown in the Americas and woven in British factories. The turn of the 19th century also saw the invention of a weaving machine that could create “bobbinet” (now known as tulle), previously made by hand. The muslin, gauze and tulle were stiffened with starch derived from corn and wheat, and were layered to form the skirt of the tutu. These light fabrics gave the illusion that the dancer was floating.

New advancements in the theater—particularly in lighting—played an important role in tutu development. In the late 18th century, theaters were lit by candlelight and ballet costumes were made of heavy silk, woven with metallic thread and decorated with spangles and sequins, which glittered in the flickering light. By the early 19th century, brighter and more even gaslighting had been invented, which created a very different effect. The new tutus glowed bright white in this light.

However, the combination of lighter-weight fabrics and gaslighting was a dangerous duo. Many ballerinas tragically died when the skirts of their tutus caught fire. The most famed was Taglioni’s protégée Emma Livry, whose costume caught fire during a rehearsal. Although fireproofing was available, many dancers refused because it made the costumes stiff and dull. Eventually, new ways of fireproofing were developed, and lighting was made safer.

The Classical Tutu

By the end of the 19th century, ballet technique had continued to evolve and so, too, had the tutu. As the demands of pointework increased, the tutu was shortened to just above the knee. While the Romantic period had favored the diaphanous quality, the late-19th-century tutu had a more defined shape and elaborate decoration on the corseted bodice. This new, shorter costume allowed more of the legs to be visible, drawing attention to new styles of footwork, petit allégro and turns.

Tutus and the Ballets Russes

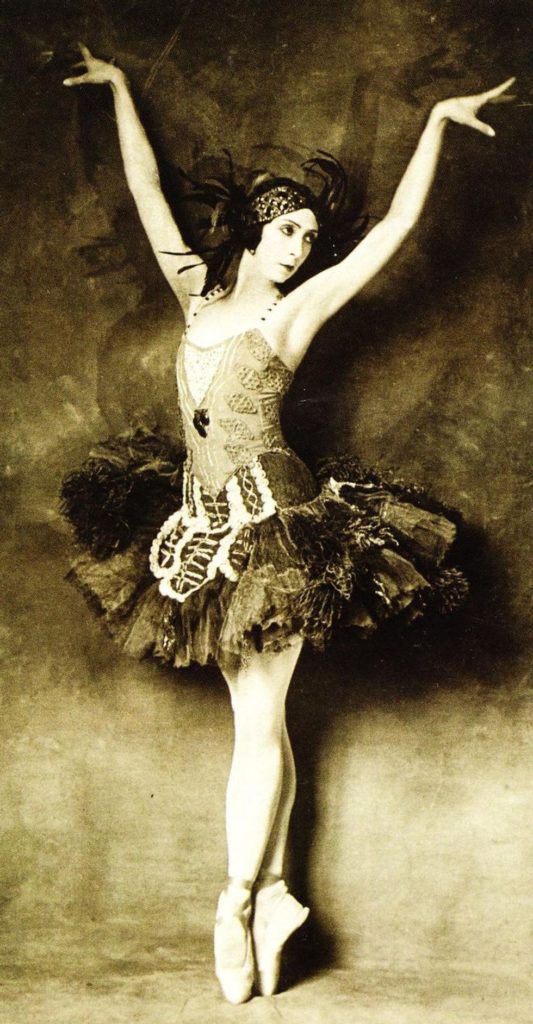

By the turn of the 20th century, the tutu was the ballerina’s stage uniform, whether she was playing the role of a gypsy or a princess. This shifted with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which rebelled against this aesthetic and designed costumes that echoed the ballets’ themes. For the premiere of The Firebird in 1910, Tamara Karsavina in the title role wore elaborate feathered trousers and a tunic; the costume was later changed to a tutu.

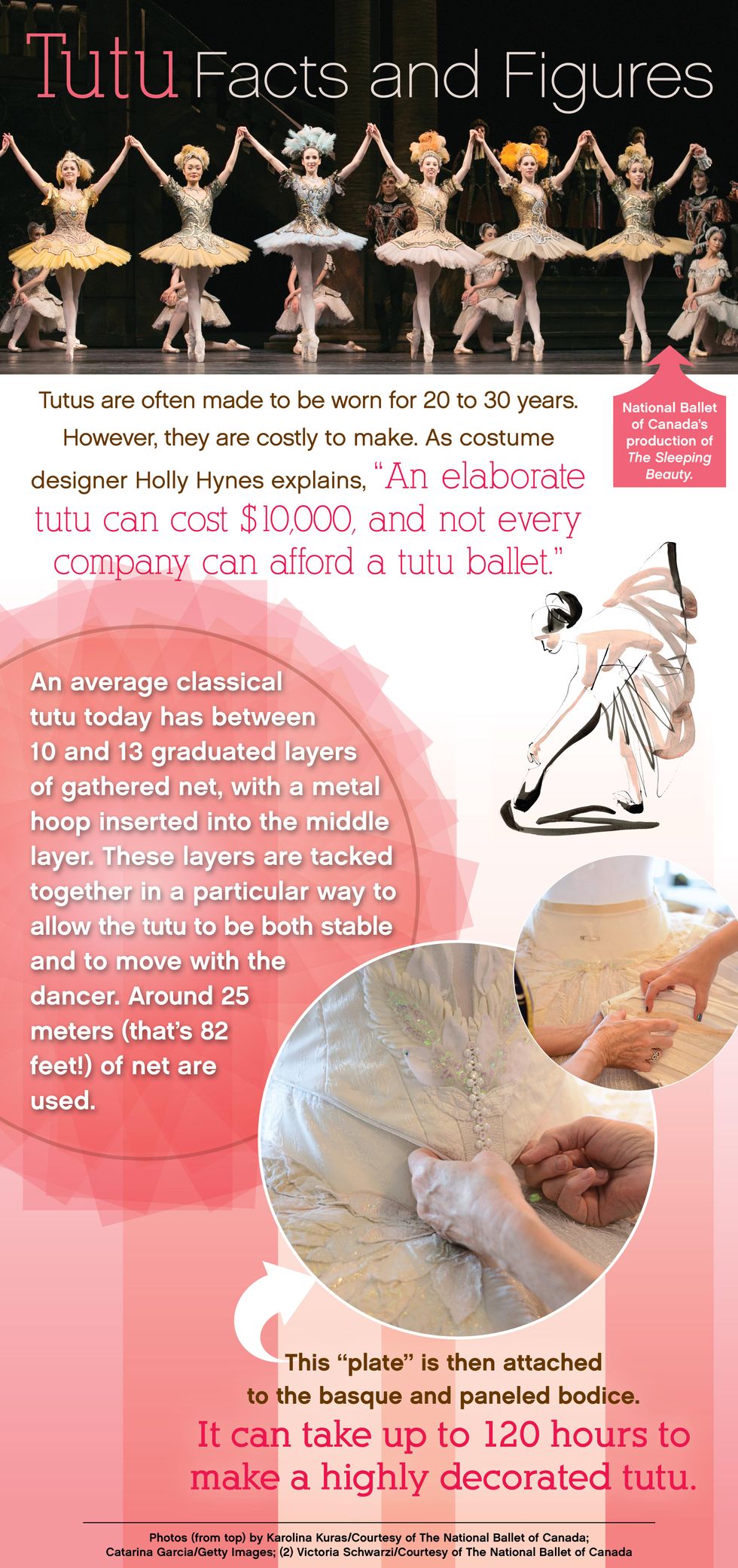

In 1921, the Ballets Russes revived The Sleeping Beauty, renamed The Sleeping Princess. Léon Bakst designed elaborate tutus that can be seen to reflect both the 1890s and 1920s styles. The tutus are almost dropped-waist, with the plate emerging from low on the hips.

Mid-Century Tutus

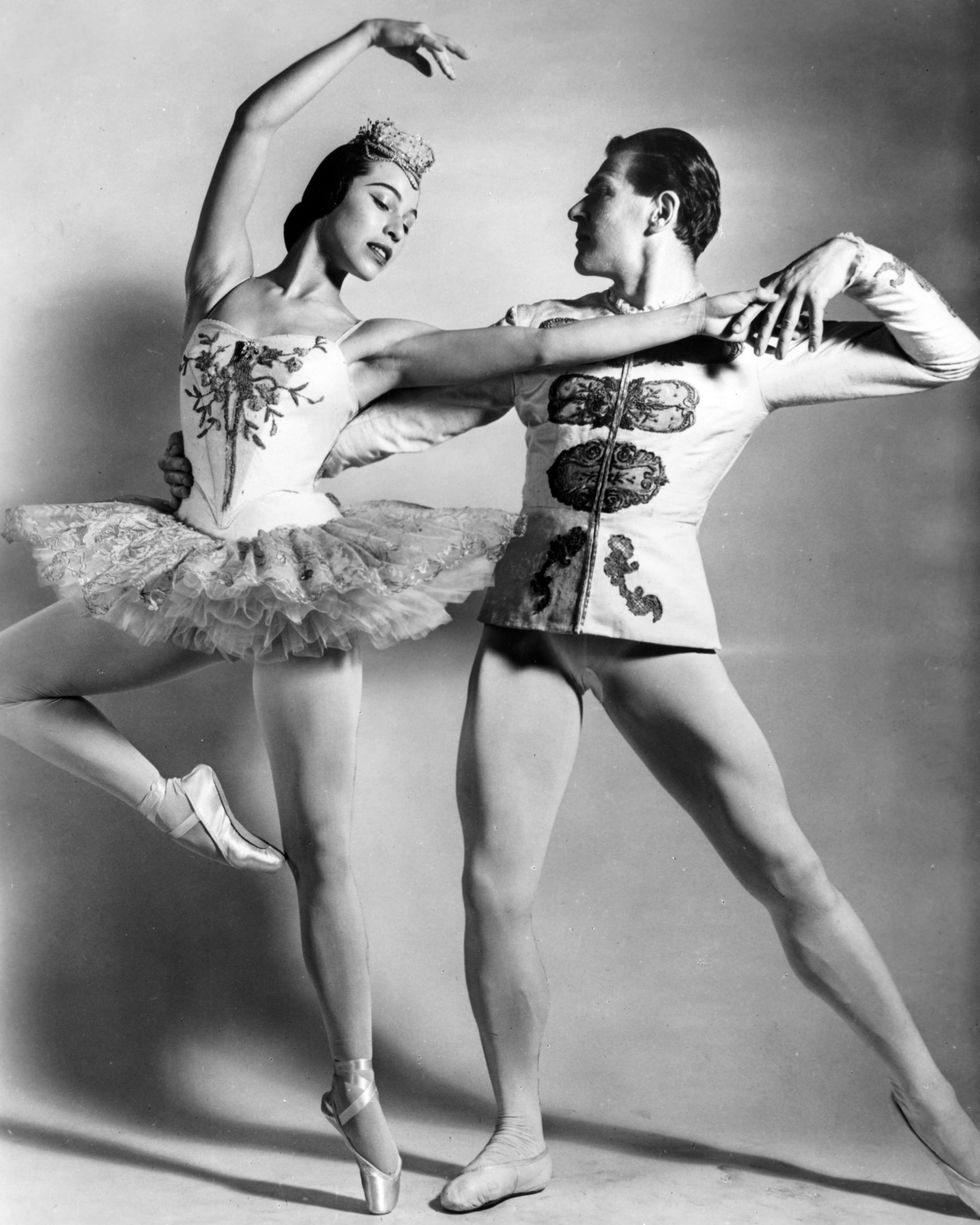

In the 1930s and ’40s, shorter tutus emerged featuring a more recognizable fitted bodice, basque (the section between the bodice and skirt) and plate. The tutu plate was now often reinforced with a metal hoop to maintain the shape and look of the shorter and higher tutus. This was the forerunner of what we know as the “pancake” tutu today.

In this video, Alicia Markova’s costume reflects this style as she dances the Nutcracker‘s Sugarplum Fairy variation at Jacob’s Pillow in 1941.

Karinska and the Powder Puff Tutu

In the late 1940s, George Balanchine wanted a tutu that allowed viewers to see the dancer’s movements uninhibited by a large, hooped skirt. Costume maker and designer Barbara Karinska created the “powder puff” tutu to solve this. This new style was smaller, shorter and lighter and used only six to seven layers of net, with no hoop.

Karinska was not new to the tutu. She had started making ballet costumes in the early 1930s, and one of her first innovations had been introducing bias (cut on the cross-grain of the fabric) to the side of the bodice, which allowed for both movement and a tight fit.

Costume designer Holly Hynes describes Karinska’s tutus as works of art. “She often would combine different colors of tulle, mixing them like paint,” says Hynes. “The illusion onstage would be one color with a lot of nuance. She also was very inventive, trying to find trims and decoration that would appear heavier onstage than they really were.”

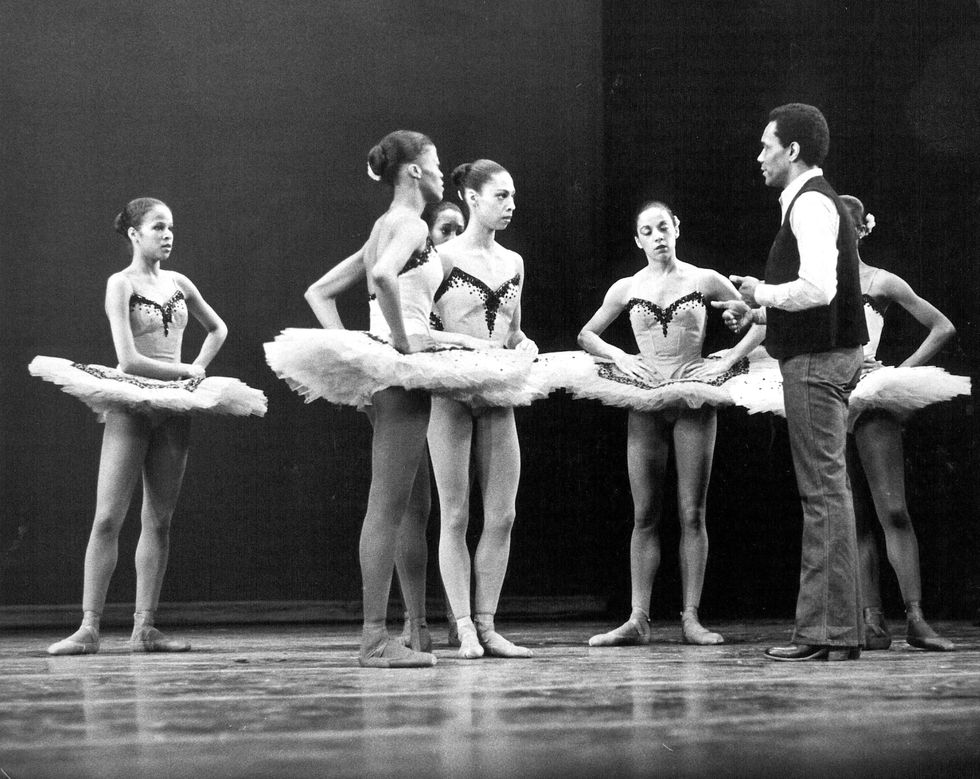

By the 1960s the tutu had gotten even shorter, reflecting the changes in both technique and choreography and showing off the dancers’ limbs and athletic movements in a new way.

Playing With Shape and Style

Over the years, designers and choreographers have played with the design and shape of this iconic garment. In 1996 Stephen Galloway designed the now iconic disc-like tutus for William Forsythe’s The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude. These costumes, while referencing the classical tutu, created a new, streamlined silhouette.

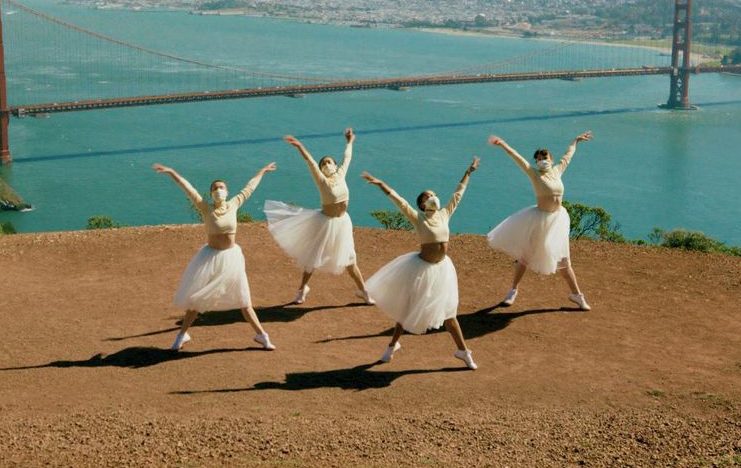

Earlier this year, The Dutch National Ballet responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by making a social-distancing tutu. This astonishing costume is three meters in diameter and made of denim.

The tutu remains the ballerina’s most iconic tool and costume. While physically distancing, it also connects the dancers of today to ballet’s rich history—interconnected with fashion, the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the ballerina.