Considering a Gap Year After High School? Here’s What You Need to Know.

Grace Li trained hard at her local studio all through high school, and by her senior year she was excited to take the next step towards a ballet career. But she and her parents knew higher education was also in her future. After Li applied to both colleges and trainee programs, she decided to defer her acceptance to Columbia University for a year-long ballet immersion in Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre’s Graduate Program. For Li, taking a gap year was the perfect choice. “It’s been transformative,” she says of her months dancing alongside a professional company, something she’d never experienced at her studio in San Diego. “I’ve gone back and forth on whether I want to keep doing this, but right now, my decision is to go to Columbia in the fall as planned, keep dancing as much as I can, and see where academics takes me.”

For high school seniors passionate about dance but unsure where, when, or how ballet fits into their futures, taking a gap year instead of heading straight to college can press pause on making tough decisions at a pivotal time. Focusing solely on professional-level training without the distraction of academics can help clarify your longer-term goals, take your dancing to the next level, and even reveal new career options. But a gap year isn’t necessarily easy to do, and there are many factors to consider and questions to ask before deciding if it’s right for you.

Should You Take a Gap Year?

A big benefit of taking a gap year is to feel what life as a professional dancer is like both mentally and physically, particularly if you enroll in a program that’s structured to mimic company life, says Raymond Rodriguez, dean of Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School. “Especially for a student coming from a smaller school without exposure to a professional company, they really get to know what a full day of dance is like. Training, learning repertoire, and performing can help them determine whether it’s something they thrive on, or if they can withstand it. The day-to-day process is very different from taking one or two classes a day while you’re in high school.”

In addition to the physical demands, Victor Alexander, director of Chicago’s Ruth Page Center for the Arts, says there’s a mental shift many students don’t anticipate and which can affect their relationship with dance. “Even if you’ve already been taking class every day, you don’t know what it means to wake up in the morning and think, I have to go to the studio because it’s my job. So taking a gap year can help them decide if they really want to be a dancer or not.”

Atlanta Ballet dancer Catherine Conley’s gap year did exactly that. She’d already been accepted to the University of Michigan, and planned to attend, when she was offered the opportunity to study at the Cuban National Ballet School through a cultural exchange program. Up until then, she’d been serious about ballet but wasn’t quite sure if she wanted it to be her career. “Cuba was going to be a sort of test year for me,” she says. “I thought I’d go and see what opportunities presented themselves before deciding whether to keep dancing or go to college.”

Conley deferred from university, and after her first year away asked for another deferment. “They said no, which wasn’t a problem, because by then I was sure I wanted to keep dancing,” she remembers. “I really needed to know what it felt like to dance full-time and not be doing anything else.”

Practical considerations like financial support and housing, as well as emotional readiness, should factor into your decision to take a gap year. Whether you’re in a trainee-style program or a self-directed one, leaving the regimen of high school takes maturity, says Rodriguez. “Especially if you’re going to move away from home, you have to be very disciplined. It can be liberating, but also difficult.”

Alexander agrees, adding that many students are caught off guard by the expectations of professional life. “It’s not just coming in and taking class and that’s it,” he says. “There are a lot of responsibilities, commitment, and discipline while you are in the process of a gap year.”

Although she had financial support from her parents, Li’s gap year hasn’t been all smooth sailing. “I knew it was going to be hard, but there’s been even more dancing and pointework than I expected,” she says. “I have to be responsible for my own well-being, take care of my body, eat right, and rest well. There definitely have been a lot of ups and downs.” The experience has allowed Li to evaluate her options, she adds. “When things are going well, I think maybe I want to do this— it’s been really cool to learn so much rep and perform Nutcracker with the company—but then I feel how hard it is and am not so sure it’s for me. So it’s been helpful to see what professional life is actually like, instead of going in blindly.”

How to Make Your Gap Year Worthwhile

Whether your subsequent plans are firm or TBD, a successful gap year hinges on maximizing your learning experience. Zippora Karz, a former New York City Ballet soloist and Balanchine Trust répétiteur who coaches pre-professional students, says thoughtful planning is crucial. “It’s important that you structure your time and are really disciplined about following a schedule,” she says. “Identify what kind of rep you’re interested in—what is your target style of dance?—but also be open to different types and take classes in those styles, as well. Because you never know what’s going to be a fit.”

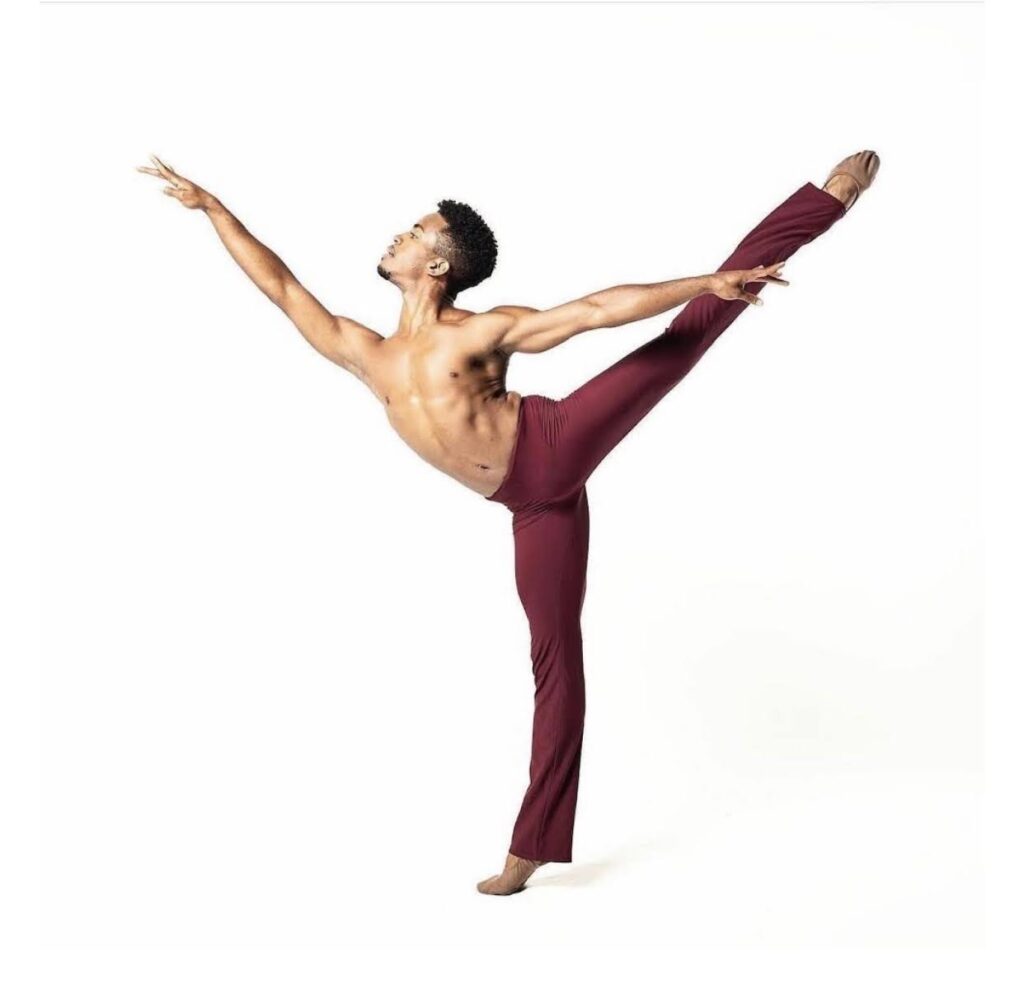

Collage Dance Collective artist Leonard Perez decided to take a gap year when he was already in college. He had simultaneously been studying on scholarship at the Ruth Page Center for the Arts for two years. Perez was nervous about interrupting his studies, but willing to take the risk to see if a career was possible. After consulting with his university’s dance-program dean, Perez left to train full-time at Ruth Page. “I was so fully immersed in all aspects of what it takes to be a professional—I walked around with my ballet dictionary and watched every video I could find. I took classes all day,” he says. “There was no guarantee of anything at the end, so I took a risk and had a plan to go back to college.” Perez’s gap year, which became open-ended when he landed jobs with several ballet companies, illustrates the necessity of balancing a structured program with flexibility.

For Conley, readiness to adapt to her shifting priorities helped her decide her next steps. “You can’t go into it thinking it’s going to take you in one direction,” she says. “So even if you’re planning to dance for a year, still apply to college, have everything in line so you have choices at the end and aren’t hemmed into one thing. Give yourself the power to choose.”

Making the Decision

Taking a gap year is a big decision. A trusted teacher or mentor can help you and your parents weigh the risks and potential rewards. “I really look at individuals and evaluate whether I think they’re right for this or not,” says Rodriguez, who often talks with students and their families to offer perspective. “I know their level of talent and personality type and can offer a realistic assessment of what might be possible for them.”

Karz says a teacher can help parents uncomfortable with the gap-year idea by talking to them about the variables, realities, and opportunities it presents. “It’s important to bring in a voice whose opinion the family will respect,” she says. “Find that teacher who really believes in you and bring them into the conversation.”

Whatever goals you have for your gap year, remember that with planning and commitment, it’s unlikely to be time wasted. “Trust that if you take this gap year, it’s going to be beneficial,” says Perez, who plans to finish his degree in the future. “Sometimes we doubt that what we’re doing will pay off, but dance training is life training. So whether this is your calling or not, dance will benefit you in any type of career you go into.”