Julie Felix Broke Barriers Onstage. Now, She’s Guiding the Next Generation.

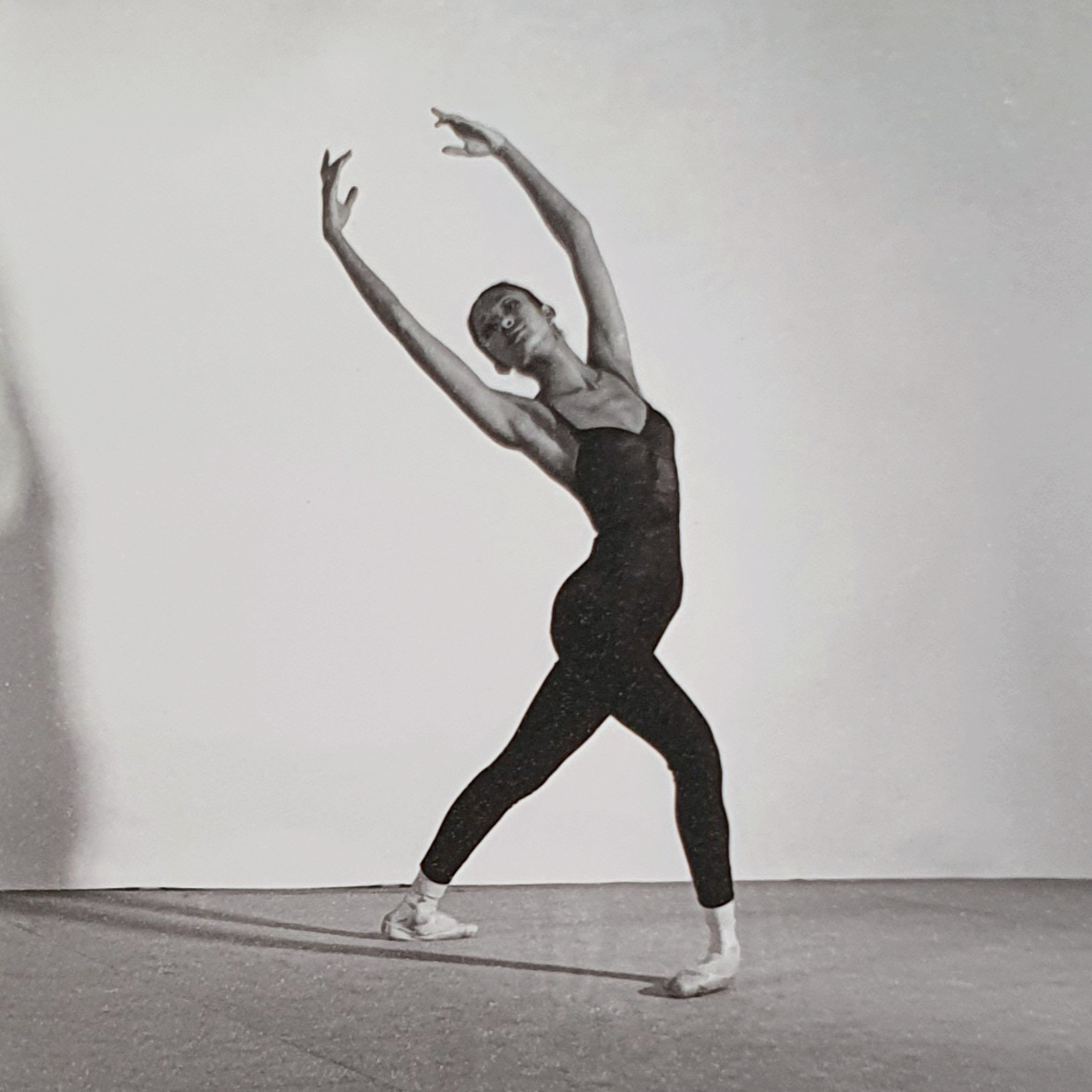

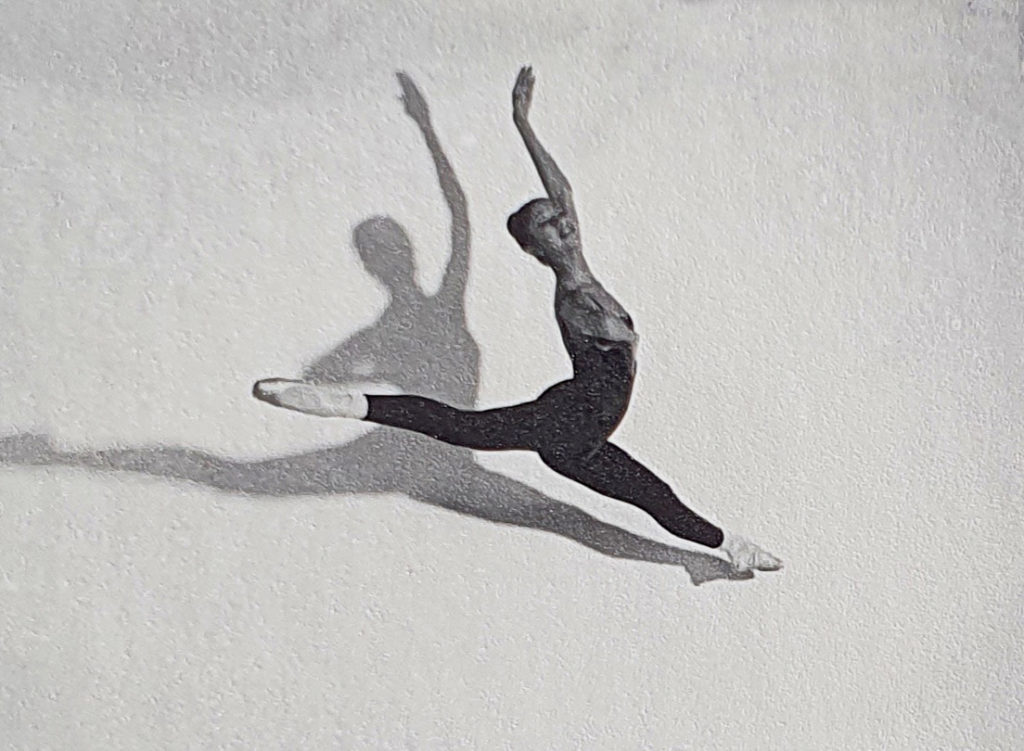

Julie Felix was never meant to be a ballerina, according to the British ballet world of the 1960s and ’70s. Onstage amid a lake of pale swans, she would only be a distraction, she was told. Instead, she took flight—to a storied career at Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Felix began ballet classes at age 7 in her hometown of Ealing, West London. Her father was Black, from Saint Lucia, and her mother was a white Londoner. In her teens, Felix won a grant from the Inner London Education Authority to attend the Rambert School of Ballet and Contemporary Dance.

In 1975, as a Rambert student, she was chosen to dance in the corps de ballet of Rudolf Nureyev’s The Sleeping Beauty with the London Festival Ballet (now English National Ballet). It seemed like her big break. But the company declined to offer her a contract at the end, telling her that her complexion was a poor fit. She would later also be rejected by The Royal Ballet.

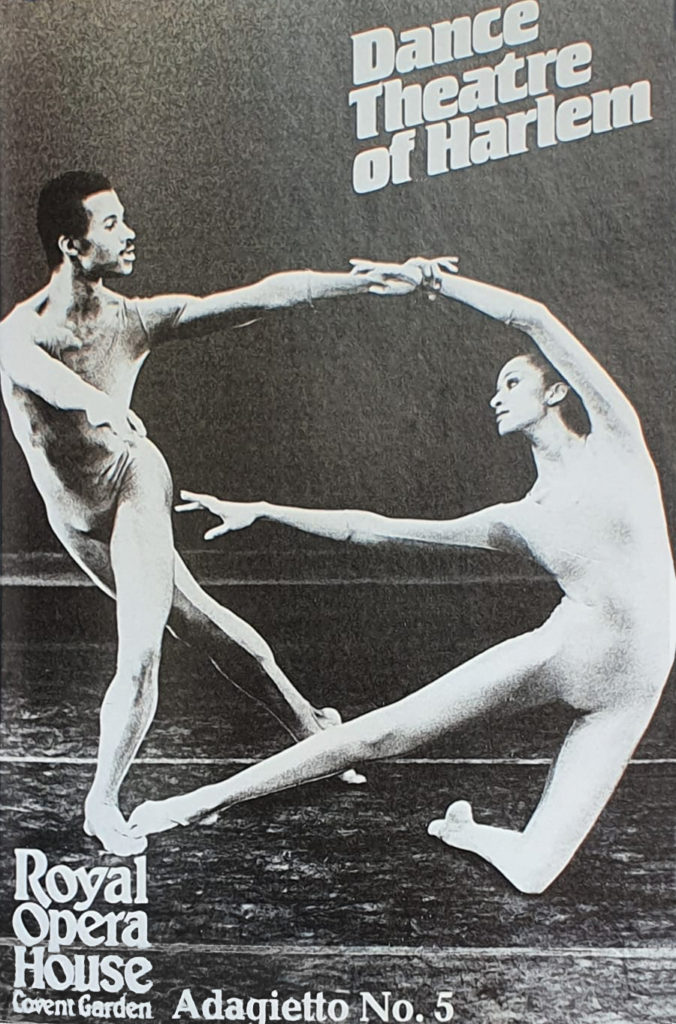

When DTH visited Britain to appear in the 1976 Royal Variety Performance, Felix took company class. Halfway through, Arthur Mitchell offered her a contract. But she turned it down due to fear of living in New York City.

She was reinvited to class with the company a few months later, when DTH returned to perform at Sadler’s Wells Theatre. Before the session began, Mitchell gave her another chance. “He said, ‘I don’t offer anyone a contract twice. If you don’t accept it this time, don’t bother coming back,’” Felix says. “So I said, ‘Yes, I’ll take it. Please!’”

She joined the company in 1977 and rose to the rank of soloist. In 1986, Felix retired and returned to the United Kingdom, where she became a company teacher and remedial coach to the Birmingham Royal Ballet (then Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet) until 1997.

This year, she began an honorary fellowship at Falmouth University to teach ballet and Floor-Barre to undergraduate students. As a dance educator in the UK, she is guiding students through a cultural climate in which diversity is increasingly recognized as a strength, while funding for arts education—like the scholarship that helped launch her career—is often considered superfluous.

“A lot of people are saying [to students], ‘Why would you get ballet training? You don’t earn enough,’” Felix says, noting the recent elimination of some UK-based university dance programs. “But if you have love and passion for ballet, then we should make it available and financially viable for these kids who want to do that.” She values the accessibility and breadth of Falmouth’s program, which combines dance and choreography.

In honor of Black History Month in the UK, Pointe spoke with Felix about her career as a dancer and instructor, and her thoughts on diversity in ballet.

The rejection you faced after dancing in the corps of The Sleeping Beauty profoundly affected you, but it didn’t stop you. What is your perspective of that experience now?

It is something I have taken with me all of my career. When I’m teaching or lecturing to my advanced students now, I tell them that when we are hellbent on one thing, we’re like racehorses with their blinders on. We, as human beings, have the strength and determination to achieve our goals, but we have to open our eyes and realize rejection is the greatest opportunity.

That rejection [by the London Festival Ballet] really was crushing, because I didn’t think my color would stop me from pursuing my dreams. But within two weeks or so, I realized that if I went along with this big chip on my shoulder and thinking nobody would want me, I might as well have just given up on my dreams.

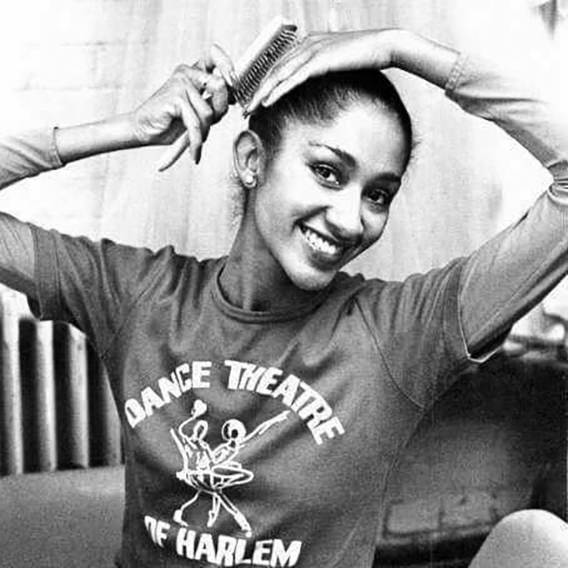

What was it like joining DTH?

From the moment I started with the company, there was camaraderie. If any of us were unsure about or struggling with choreography, we could go to Virginia Johnson, for instance, and she would help. There was not this jealousy that they have in some companies now. We were a big family.

You had to adapt to the American training style—which was slightly more intense than what you were used to—and meet Mitchell’s high standards. Could you talk about that?

One of the first things he said to me after one or two classes was, “Missy, we’re going to knock that British out of you.” I took such umbrage to it, but it didn’t take me long to realize the difference in training was leaps and bounds from what mine was.

In the English style, the lines were very soft. It was almost considered vulgar for the legs to be too high, although my training was more Russian. My teacher at Rambert always said, “Get your legs up. Be as strong and larger-than-life as you can.”

However, when it came to being in the studio and rehearsing with Dance Theatre of Harlem, I thought, How am I ever going to get myself up to that standard? I had always thought that I worked to my fullest capacity, until I started working with Arthur Mitchell. He had this way of just getting everything, like blood out of a stone. He was very tough, but never nasty or mean.

Was that your first time thinking of ballet as a way to represent something bigger than yourself in the way Mitchell wanted for that company?

Absolutely. I’ve never met—and still probably will never meet—anybody as tirelessly devoted and self-sacrificing to a cause. This is why I was so honored to have been offered a contract with the company, because he believed that each and every one of us had made sacrifices and deserved to be there.

What was your experience learning works by George Balanchine?

There were certain pieces that I initially struggled with because the footwork was very fast. Agon and The Four Temperaments were very unusual, with the hip thrusts, and quite angular.

Which pieces in the DTH repertoire had the greatest impact on you as an artist?

I love Serenade. We did it nearly every time we went on tour. It might have been one of the first Balanchine ballets that I learned. I ended up having to do lots of different parts in it as I progressed at the company. I was able to jump in at any given opportunity.

We did a piece by Geoffrey Holder, Dougla, which is a signature work. Being barefoot was quite different for me.

In a company like that, you would never get bored with the repertoire, because it’s so diverse and it always challenges your body.

What are your thoughts on the state of diversity in both British and American ballet today?

I’m finding that the major ballet companies in the UK are very slowly integrating, but I still get a feeling that it’s tokenism, so they’re seen to be doing the right thing by bringing the Black or mixed-race dancers. It’s been getting better, but it’s not enough. Whereas, in America, some of my former colleagues who are still teaching or directing are doing their bit and it is getting better. It could be also because Dance Theatre of Harlem was in America, and they carry that [legacy] still.

I’d like to think that it is moving quicker, and it’s just about getting the UK to see that if we’re talking about including everybody, then that should be everyone. Not segregating Black or mixed-race people out of the classical equation.

What do you think should be done to increase access to ballet?

When I was with Birmingham Royal Ballet, [then–director of learning] Jane Hackett and I started a program called Dance Track. We would put on lecture demonstrations at schools for inner-city kids who couldn’t afford to go to the ballet.

There was a host school that we used, and we would go to feeder schools, hold auditions, and choose the kids who had never done ballet before and met certain criteria. Then, we would put on an after-school ballet class every week for each of these schools. But one class a week is just not enough.

Now, there’s a gap that needs to be filled from where they finish at 8 years old, because then, there’s nothing.

I don’t know how best for us to move forward other than introducing more programs across the nation like Dance Track, where you are targeting young people, but making it a really fun, interesting program.

What is your approach to teaching?

I’m a good teacher because of the adversities I endured. As horrible as something is, you can salvage it and make something better of it.

Go through the process to find out why something’s not working. A student might say, “I can’t do those pirouettes,” but I’ll tell them, “Yes, you can. Just strip it back to its bare essential technique.” That’s not just for pirouettes, it’s through life.