Real Life Dance: Creating A New Nutcracker in Key West

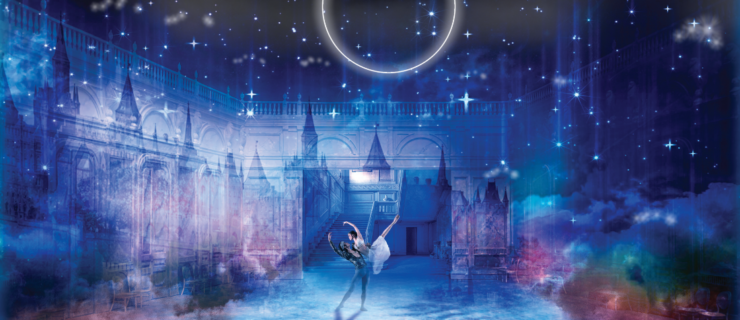

Nutcracker

has gone south for the season. The Key West Nutcracker is set to debut on December 16 and will run through December 18 at the Key West High School, in Key West, FL.

It all started in summer 2001, when producer Joyce Stahl had dinner with her daughter, Julie, at a cozy New York restaurant. Stahl had recently moved to Key West and was in New York to escape the consuming Florida heat. “We started talking about what a Key West Nutcracker would be like,” Stahl laughs, remembering that they thought of substituting free-roaming chickens and roosters that are everywhere in Key West for mice and the Rat King.

Both were familiar with the traditional Nutcracker story: Stahl had performed for 27 years as Madame Stahlbaum in the original Princeton Ballet Nutcracker, and Julie had danced professionally with Eliot Feld’s company and Hubbard Street Dance Chicago.

The subject planted a seed. “I started to write down ideas on how the traditional story could be made Key West–specific,” Stahl says. She wanted to follow Audree Esteé’s choreography for the first two scenes of Act I, so she called American Repertory Theatre. “They gave me permission to use the choreography.”

Scene three, however, would allow for creative story development, because it was the beginning of Clara’s dream. Stahl turned to Angela Whitehill, founder of Burklyn Ballet Theatre, who had directed Stahl’s daughters during the early stages of their dance careers.

“I was thrilled!” Whitehill recalls, but she knew the production would not be easy in Key West. Supplies for the costumes and sets such as fabric, ribbon and paint had to be shipped in, as would an excellent choreographer, dancers—and a floor.

Money was the first concern. Stahl contacted local funding sources, including a major bank and nonprofit organization. But none would commit; finally, she got tired of waiting. “So I decided to do it myself,” she says. She and Whitehill worked up a preliminary budget of close to $400,000, and Stahl hired seamstresses to begin constructing the traditional Victorian-style Act I costumes that Stahl would design.

“Joyce asked me to design the Act I snow scene costumes and all of the costumes for Act II and [make] them Key West–specific,” Whitehill says. “My imagination went wild: snow birds, angel fish, sea anemones, sea sprites, sharks, shrimp.…”

The two decided that all of Act II would take place underwater, with the characters descending from the surface in a diving bell and meeting denizens of the deep, including King Neptune. None of the Act I or Act II costumes would be bought or borrowed; all would be designed specifically for this production. Whitehill hired a costumer in Vermont to work on sea anemones, starfish and sea sprites, a seamstress in Chicago to make snowy egret feathered skirts, and a costumer in Indiana who had special skill in building animal costumes for dance.

At the same time, Stahl hired two well-known Key West costumers: one to build headdresses for roosters and the other to build the chicken costumes.

Then came the question of music. Although a Key West Symphony Orchestra exists and the idea of live music seemed irresistible, Stahl and Whitehill realized the theater would not hold all the musicians, and it wouldn’t work to pare the numbers down, so they settled on recorded music.

Next, they cast the ballet. In September, Stahl conducted local auditions for the Act I party scene. “I used Keys Kids, a local children’s theater group,” she says, filling in adult roles with parents and relatives. “Altogether, we have a local cast about of 45 people.”

Whitehill lined up the principal roles. By the end of summer 2005, she had eight professional dancers under contract—four women and four men. These dancers were drawn from companies around the country that do not perform a Nutcracker. For the Sugar Plum Fairy (Sea Fan Fairy in this production) and her Cavalier, Whitehill contracted Wendy Whelan and Nikolaj Hübbe of New York City Ballet.

Whitehill also brought in Alun Jones, former artistic director of Louisville Ballet, for his sense of humor and contemporary choreography, which would be ideal for Act II. “When she said, ‘Nutcracker,’ “ Jones recalls, “I was about to say no, but when she said, ‘Key West,’ I said yes!”

Jones adjusted his thinking to the underwater world of Act II. “I decided to have the sea sprites [Arabian] lyrical instead of sexy and provocative and to use veils so there’s continual water-wavy movement. I saw the yellow sharks [Russian] as sinister, looking to attack one another; I saw the sea anemones [Waltz of the Flowers] as traditional, because the music is so recognizable, and the story needs to return to its beginning.”

Stahl hired an experienced set designer, Michel Boyer, to do the sets for Act I and Act II. Boyer kept to the Key West motif for the Act I party scene. “It’ll be an enlarged version of an outdoor backyard with a fence, palm trees and vines,” says Boyer. “The sun will be setting, and the clock will show.” As Clara’s dream develops, the backyard items grow and the tree, a Norfolk pine (very common in Key West), will stretch from 7 feet to more than 20 feet. As for the magical snow forest, “We’ll make that into a mangrove swamp with the roots showing,” he adds.

By October, the production elements were coming together. Jones would begin working with dancers the last week of November. Until then, he plotted the number of dancers and order for each variation. Boyer (also acting as technical director) continued to build sets, designing stage entrances and exits, planning special effects. Whitehill coordinated schedules and rehearsal spaces, meeting with theater and program staff and crew to decide on logistics. Stahl managed the budget, established where the dancers would stay and coordinated all aspects of the final production. It’s Stahl who has the final word: “I kept thinking it would it never happen…but now it is!”

William Noble is the co-author of The Nutcracker Backstage and three other books on ballet.