3 Dancers Share What They Learned From Training Abroad

Many ballet students take the step of moving to a new country to continue their training. And while it’s not an uncommon story, like any new endeavor, it can have both its challenges and its highlights. Pointe spoke with three dancers about what their time training abroad taught them.

Sojourn Gudorf Johnston, Ballet Frontier

Sojourn Gudorf Johnston always knew she wanted to train abroad. Originally from Vermont, the now-22-year-old Ballet Frontier dancer was drawn to the English National Ballet School as a teenager for its curriculum and performance opportunities, as well as the chances it gave to work with various choreographers. Johnston had also seen a DVD of English National Ballet in Akram Khan’s reenvisioned Giselle. “His choreography has such strength and power but is also very raw, and that’s something I connected to,” Johnston says. Knowing the school and company sometimes worked together, she felt that attending ENBS might lead to “some great opportunities.”

Johnston was accepted into the school at 16 and headed to London, where she had classes in Cecchetti, RAD, and Bournonville technique, as well as the Ashton style. She had to adjust to a softer, more fluid style of dancing, which differed from her previous Vaganova training, as well as a different sense of musicality. “It is less about hitting the beat,” she says regarding ENBS’ training. “They were more about flowing through the music.” Yet working in different techniques strengthened Johnston’s versatility. “It allowed me to develop myself as a dancer.”

Johnston also got to work with European choreographers, including Didy Veldman, Juan Eymar, and Ruth Brill. During her second year, she was selected for a rehearsal cast for Khan’s new piece, Creature, but the pandemic shutdown forced her to temporarily return home to the U.S. Still, she thinks it’s “pretty cool” that she almost had the opportunity to rehearse with him after finding his Giselle so captivating.

Working in various styles with different choreographers at ENBS helped prepare Johnston for company life at Ballet Frontier, where artistic director Chung-Lin Tseng choreographs many of the company’s productions. The versatility she developed has also proved useful, tapping into her Vaganova training for Ballet Frontier’s Carmen and drawing on her English training for ballets like Romeo and Juliet. “You can watch different styles, but until you actually do it and see what fits your body best, you don’t know what kind of dancer you are.”

Sahel Flora Pascual, Ballet Austin

Ballet Austin’s Sahel Flora Pascual enrolled at the School of American Ballet when she was 15, but her path there wasn’t straightforward. Originally from the Philippines, Pascual was encouraged by her teacher to audition for programs outside the country. “I wanted to be as fully rounded a dancer as I could be, so going abroad was the best way for me to really get a taste of all that was out there.” Pascual, who’s half Filipino and half African American and Jamaican, looked to the U.S., where she had family and where her teacher had danced. She first spent a year at the Kirov Academy in Washington, DC, at age 14. She then attended the summer program at SAB and was invited to stay for the winter term.

Pascual joined SAB when the school was taking steps to prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion, including the integration of skin-tone tights and shoes into the dress code. In the Philippines, Pascual didn’t have a teacher who embodied her Black identity, so learning from SAB associate chair of faculty Aesha Ash is something she’s “forever grateful for.” While Pascual’s previous training in the RAD and Vaganova techniques gave her a “solid technical base,” SAB’s Balanchine style allowed her to develop her artistic expression and instincts. “Balanchine is a really good lens to work through because it gives you all these different skills,” says Pascual. “You can move really fast and you can move really, really slow. It allows you to explore the expanse of every single little step.”

In addition to Balanchine repertoire, Pascual also enjoyed learning pieces by William Forsythe and Jerome Robbins at SAB, as well as watching the work of choreographer Kyle Abraham at Lincoln Center, and exploring the wealth of art in New York City. But home was never far from her mind. “My coming to the U.S. was not out of an unsatisfaction with what was in the Philippines. It was really just me wanting to grow my identity and my skill set.” To dancers considering training abroad, she says: “Allow your history to influence you, but take on all the new experiences that you will have. You will have the unique ability to share your own culture, your own identity, in an original way.”

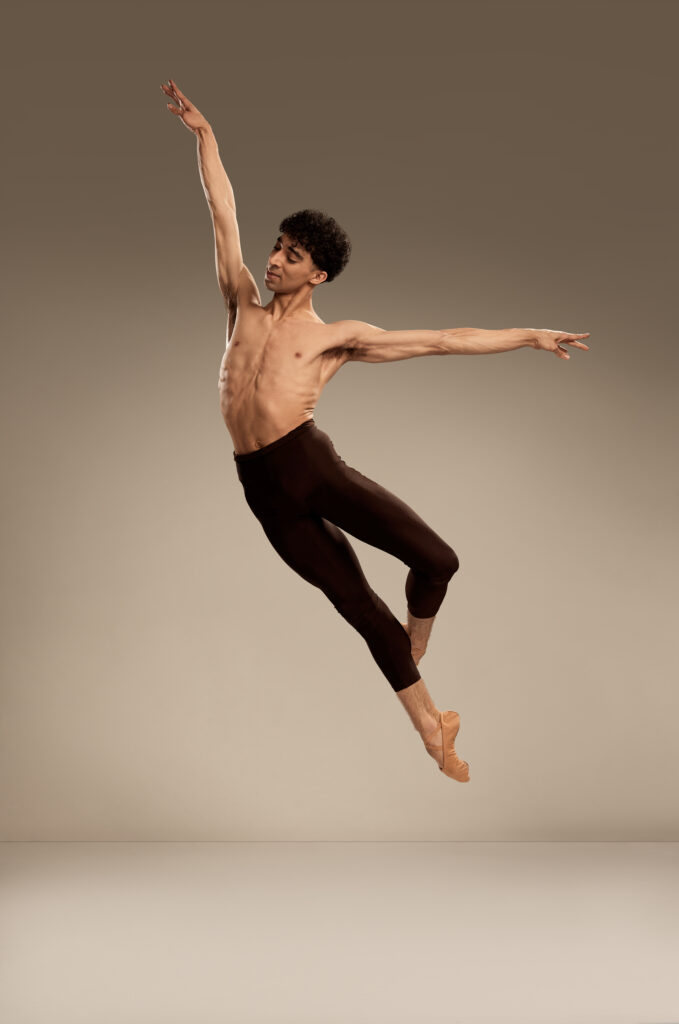

Cato Berry, Colorado Ballet

Colorado Ballet corps de ballet member Cato Berry has danced for as long as he can remember. Originally from Seattle, Berry, along with his sister, attended his mother’s ballet school before he continued his training at The Rock School in Philadelphia as a teenager. But he wanted to train abroad. Then at 14 he was offered a scholarship to Tanz Akademie Zürich in Switzerland after participating in Youth America Grand Prix. Leaving home was difficult, especially after so many years training with his mother, but Berry says it gave him a chance to develop himself. “A change of environment really helped me grow personally and professionally as a dancer.”

Berry faced new challenges in Switzerland, from daily German lessons and stressful ballet exams to strict teachers and missing home. But he liked the “tough love” training in Zurich. “At that age, when you’re a young boy, it’s easy to just coast, and there they were really on top of me, and I just ate it up.” One of his favorite memories is of working with his classmates to remember the combinations from their three-hour set ballet class. (Forgetting a combination risked being called out by their teacher.) “It was a nightmare, but we’re in the nightmare together, so it was fun,” he recollects.

While the regimented training in Zurich prepared Berry for company life, living abroad taught him independence. Without a parent to speak on his behalf, he had to learn to communicate with the school about how he was doing. “If I wanted to go to the doctor, I had to tell the director. I couldn’t just skip class and have my mom email for me,” he says. “I had to take responsibility.”

Not only did Berry develop important skills while abroad, but his relationship with ballet also changed. Growing up he viewed ballet as his sister’s “thing,” but going to Zurich made him fall in love with ballet for himself. “I don’t want to ever stop,” he reflects, “This is mine. This is what I love.”