Helen Pickett Creates a New Crime and Punishment for American Ballet Theatre

Historically, ballet has championed the ethereal and otherworldly—myths and fairy tales. Helen Pickett’s latest full-length could not be a further departure from that. Crime and Punishment, running October 30 through November 3 during American Ballet Theatre’s fall season in New York City, scrutinizes human nature as done in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1866 novel.

Pickett tells Pointe that while some people may find the hefty piece of Russian literature intimidating, she finds it to be a riveting page-turner with enduring relatability. “It is a devastatingly modern psychological thriller,” she says.

The novel’s protagonist, Rodion Raskolnikov, is complex. An impoverished student living in the slums of St. Petersburg, his fierce distrust of Russia’s bureaucratic system inspires a manifesto in which he argues that a special “extraordinary” group of people are exempt from the law, so long as they act in favor of the greater good. Believing he falls in this category, he murders a crooked pawnbroker and then her sister, an innocent bystander, as well. To his dismay, his hypothesis backfires; his inner turmoil and guilt drive him to eventually confess.

“The reason why Dostoevsky is so brilliant is that he never lets the reader off the hook,” says Pickett, explaining that Raskolnikov is a complicated human who also saves a woman from killing herself and gives the last of his money to a destitute family. “[Dostoevsky] does not let us say, ‘This person is all bad, and he’s going to be caught and killed.’ No. He puts these things in our way to remind us that people are many things.”

In the ballet, that complexity permeates not just the plot but the choreography. Pickett is an adamant collaborator; she has co-created Crime and Punishment with her longtime partner, co-director James Bonas, who provides expertise in theater and opera. Pickett, who also has a background in theater, has worked with Bonas to build scenes off of the treatment they adapted together from the novel. The two relish the chance to join effort with the other members of their creative team, including Pickett’s 12-year assistant choreographer Sarah Hillmer—and the dancers themselves.

“Helen’s always really interested in the possibilities that the body offers,” says Bonas. “The cross-sharing of ideas in the room breathes a kind of language; it will be a complex mixture of both male and female.”

Pickett and Bonas decided to make the role of Raskolnikov open to dancers of all genders. “Through that prismatic quality of different people, you start to get the complexity of the person in the book,” Bonas continues. During ABT’s fall season, Raskolnikov will be danced by principals Cassandra Trenary and Herman Cornejo, and soloist Breanne Granlund.

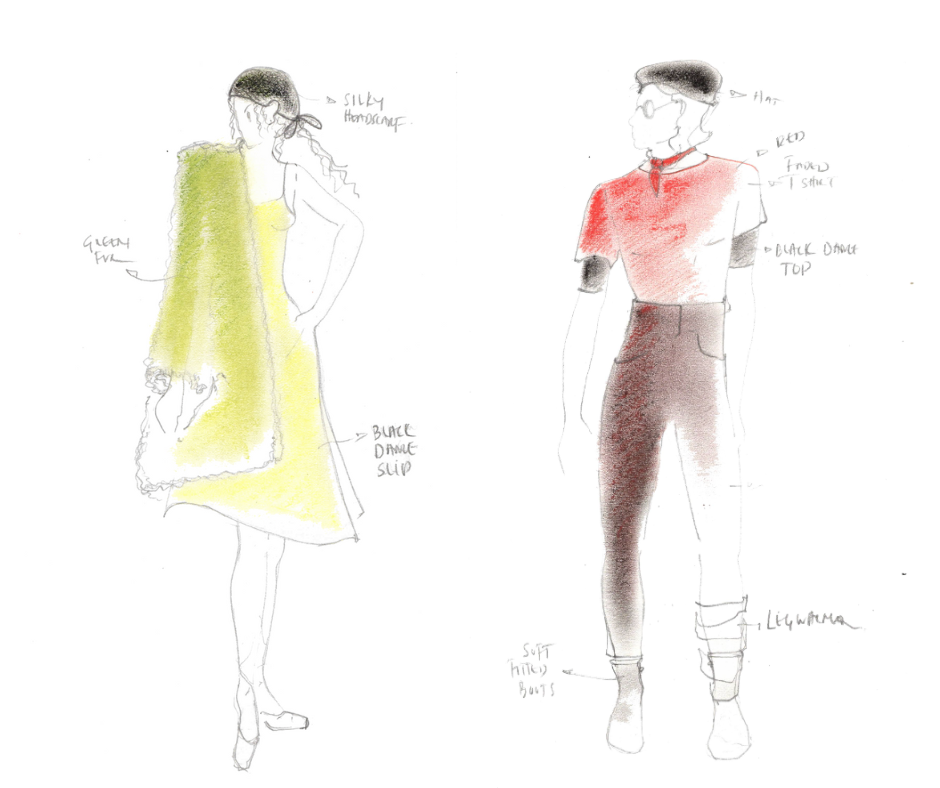

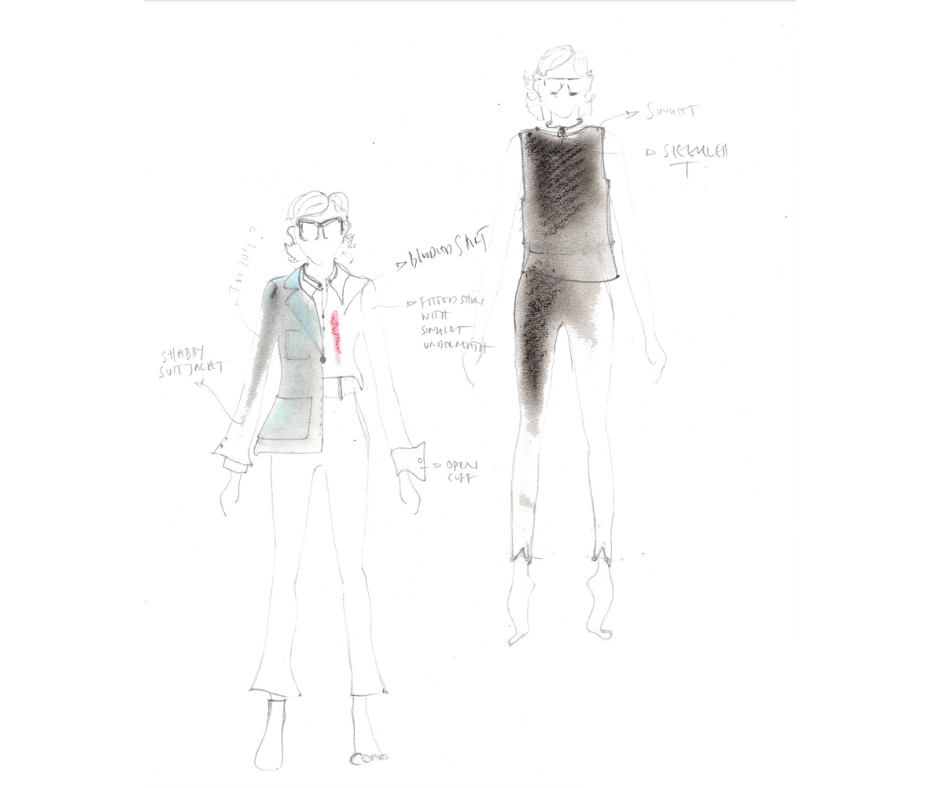

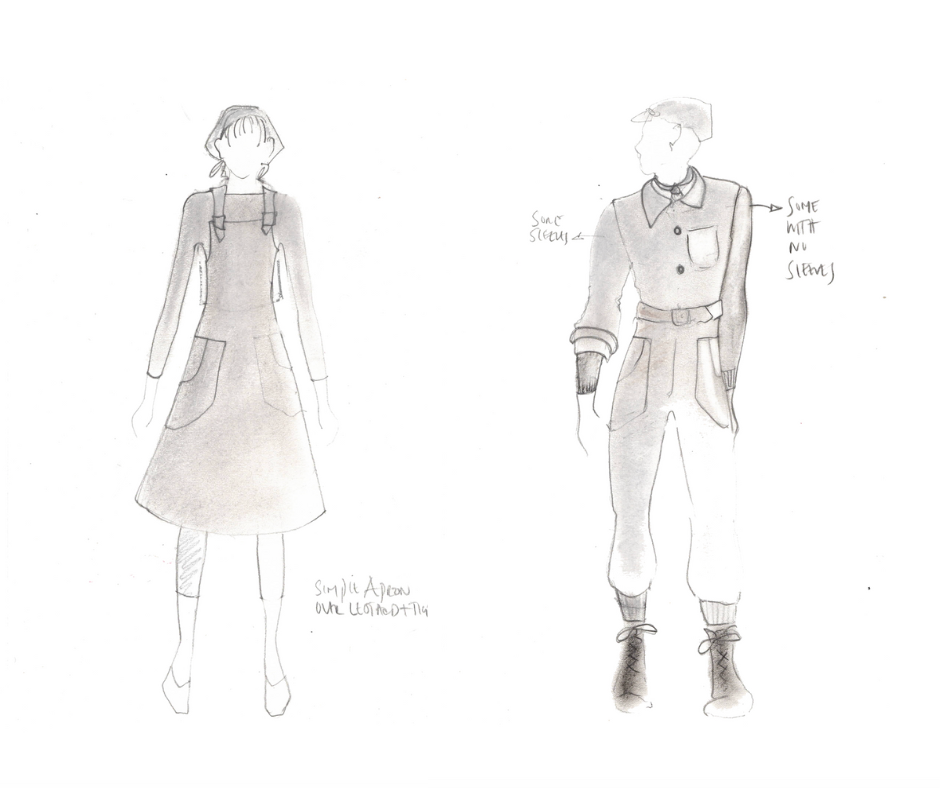

In addition, Pickett and Bonas decided not to anchor the ballet to any specific time period, nor even to Russia. While Soutra Gilmour’s set and costume design will include nods to the source material—an 1860s-inspired hat, for example—the overall look will be simple, almost scaffold-like, with the goal to demonstrate the novel’s “eerily modern” elements, Pickett explains.

Crime and Punishment will feature the largest corps Pickett has used to date. Her choreography for the 28 dancers, called Citizens, is highly individualized for the majority of the ballet. In one scene, however, they work collectively to create an important character—the City. Together, their synchronous movement creates the effect of overwhelming heat and population.

“It became very evident that the city was a heart, and a motor,” she says. “It was something relentless and would not let up, regardless of this murder.” To heighten the effect, Gilmour decided to costume the proletarian corps in a grayscale spectrum. “They’re kind of innocuous,” Pickett says. “That’s what poverty does: It erases identity.”

The ballet will also feature a commissioned score by TV and film composer Isobel Waller-Bridge, lighting design by Jennifer Tipton, and videography by Tal Yarden. Pickett explains she did not want to show an explicit portrayal of the murders in real time. Instead, Yarden’s video design, which will be projected both on a screen and onstage, will show close-up flashbacks, as Bonas explains, that hint toward what happened. “It gives us a chance to explore the inside of [Raskolnikov’s] head,” he says.

Pickett has created different movement signatures for each character and adds that she has aimed to give the ballet’s women—particularly Sonya, Dunya, Katerina, and Raskolnikov’s mother—more agency onstage. Her trademark use of opposition in the torso will, as always, be present, but, she explains, that sense of bodily torque takes on another level of meaning in this work: “It’s the oppositions within, the yin and yang of this character, this conflict, that we’re trying to capture.”

“It’s very rewarding for an artist to discover the liminal spaces of being human,” Pickett continues. “This is a heavy story, but it’s been a really diffusively joyful time working with these people. I love the tangle of humanity; maybe that’s why I’m drawn to these stories.”