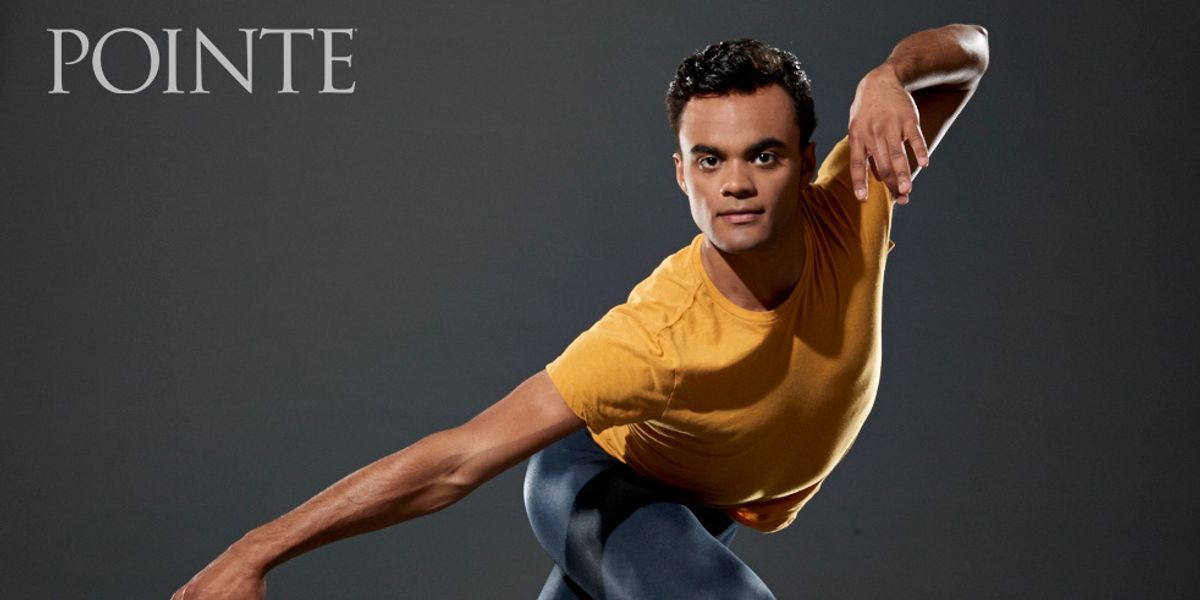

Moving Muse: Taylor Stanley Comes Into His Own at New York City Ballet

This is Pointe’s August/September 2015 Cover Story. You can subscribe to the magazine

here, or click here to purchase this issue.

Visit a New York City Ballet rehearsal on any given day and you may find an unlikely guest named Theo, a 3-year-old Shiba Inu with wolf-like eyes and a teddy bear coat who has become something of an NYCB mascot. He tends to sit patiently off to the side, lost in his own thoughts, while his owner, the captivating 24-year-old soloist Taylor Stanley, concentrates in the center of the studio, displaying his usual discipline and quiet focus.

“I bring him everywhere I go,” says Stanley. And like his canine companion, Stanley is a popular presence. “He brings a ray of sunshine into our workspace,” says fellow soloist Erica Pereira. “He’s a very good person on the inside and people feed off of good energy.” But that cool demeanor belies a high-voltage internal spark. “When he dances he eats up the stage,” says principal Robert Fairchild. Indeed it’s Stanley’s unique ability to combine power and passion with ease and humility that has made him a magnetic presence onstage and one of the company’s breakout talents.

Sharing a moment of camaraderie in Justin Peck’s “Rodeo: Four Dance Episodes.” Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy NYCB.

Sharing a moment of camaraderie in Justin Peck’s “Rodeo: Four Dance Episodes.” Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy NYCB.

Stanley’s rise at NYCB has been remarkable: After a year at the School of American Ballet, he became an apprentice in 2009, a corps member in 2010 and a soloist by 2013. In that time, he has proven himself in both romantic roles (dancing Romeo while still in the corps) and the neoclassical works of George Balanchine. But Stanley has also distinguished himself as one of the most sought-after collaborators in new creations, developing a particularly fruitful artistic bond with NYCB’s new resident choreographer, Justin Peck.

Stanley’s journey began in Philadelphia, where a performance of the Pennsylvania Ballet inspired him to attend his first ballet class at age 3. “I was terrified because it was me and all these girls,” he says with a laugh. But he was unleashed, too. “I loved moving around and being crazy and free.” His early training at The Rock School for Dance Education’s west branch also included tap, jazz and hip hop; for a while, he entertained fantasies of moving to Los Angeles to pursue a commercial career (dream gig: Missy Elliott). But a summer intensive with the Miami City Ballet School at age 15 introduced him to the broader world of ballet. “I was drawn to the professional side of it,” he says—and specifically to the challenging work of George Balanchine.

The decision to focus on ballet was pivotal, both for his training, and for his personal development. “I had to sacrifice the jazz and all the other styles that I felt more comfortable in,” he says. Pursuing a professional path required a leap of faith. But he found support from his teachers, like former Rock School faculty member Jennifer Wheat, and his parents, whom he calls his biggest advocates. “I needed the encouragement not to fear change or growth.”

Stanley in Balanchine’s “Square Dance,” a signature role. Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy NYCB.

Stanley in Balanchine’s “Square Dance,” a signature role. Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy NYCB.

At 17, drawn to the rigorous training provided at the School of American Ballet and the allure of Balanchine’s entire ballet library, Stanley enrolled in SAB’s summer program and was asked to stay for the year. Following a bravura turn in Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes at the school’s year-end workshop, he was offered an apprenticeship with the company.

As an apprentice, he originated a role in Benjamin Millepied’s Why am I not where you are, and was tossed last minute into a performance of Jerome Robbins’ N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz, where he excelled, drawing on his earlier jazz training. That string of opportunities proved he was ready for more, and soon ballet master in chief Peter Martins cast him as the lead in his Romeo + Juliet.

For Pereira, who danced opposite him as Juliet, his good energy in class suddenly wasn’t enough—she had to feel secure in his arms, too. Turns out, this is one of Stanley’s strengths. “I never have to worry,” she says. “It’s rare and it’s really special when you come across a partner that’s willing to make it work for the girl.”

Yet even while partnering, Stanley maintains a sense of individuality. Other men may look down at their partner’s waist with stern concentration, but Stanley remains alive in the moment, projecting to the balconies. And when dancing solo, he effortlessly mixes precision with grandeur—a regal presence that’s lit from within.

It’s a combination that makes him something of a muse for choreographers, including Martins, his colleague Troy Schumacher (Stanley dances in his contemporary side project, BalletCollective) and Peck, who has cast him in each of his works for NYCB, including two upcoming premieres. “He’s the most accurate interpreter of my movement style,” Peck says. He cites Stanley’s strong work ethic, lightning-quick learning and smart musicality as reasons why he’s such an invaluable contributor to the creative process.

Stanley with his dog Theo. Photo Courtesy Stanley.

Stanley with his dog Theo. Photo Courtesy Stanley.

“Taylor can be shy, but he feels comfortable enough to let his guard down in my work,” says Peck, who notes that Stanley, who had a featured role in last year’s Rodeo: Four Dance Episodes, “really acted with his soul in the piece.” The feeling is mutual. “Justin allows you to find yourself,” Stanley says. “I don’t have to be anything else but me, and that feels nice.”

Stanley’s true self can be tucked away during working hours, but ballet master Kathleen Tracey says there’s a goofiness that comes out occasionally. More often, he’s intensely focused, which his colleagues say is both a factor in his success, and sometimes a challenge. “He’s very modest, and he can be self-deprecating,” says Tracey, sometimes to the point of being too self-critical. Pereira agrees. “It’s hard for me to watch him beat himself up sometimes,” she says. “I’ve stopped him a few times and told him, ‘Don’t worry about the small things, don’t show it.’ ” Both say that he has taken those suggestions to heart over the years and has become a more mature and confident performer. “He dances for himself now,” says Pereira.

Stanley in Jerome Robbins’ “N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz.” Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy NYCB.

Stanley in Jerome Robbins’ “N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz.” Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy NYCB.

Stanley acknowledges the long process of getting to that point, crediting one role in particular with helping him face those challenges: the lead in Balanchine’s Square Dance, where he finds strength in the introspection and contemplativeness of the male solo. “That was my catalyst,” he says. “Letting go of the fear and waking up the soul and exuding something that’s bigger than me.” It has since become one of his signature roles.

Stanley says that while he thinks about becoming a principal, “I’m content with who I am and my journey so far. And I have other artistic endeavors that I would like to have a shot at.” Extracurricular activities scratch that itch, whether dancing with BalletCollective, attending a Nederlands Dans Theater intensive this summer, taking Gaga classes or pursuing a BA in liberal arts through St. Mary’s College of California LEAP program. He’s also ready for more challenges on the Lincoln Center stage—creating new work with Peck and getting a crack at more of Balanchine’s black-and-white ballets, including his dream role, Apollo. It’s a full load, but Stanley seems almost incapable of keeping his curiosity in check.