How Threatening Is a Back Fracture to Your Ballet Career?

Since she was 5 years old, Josie Walsh, now artistic director of the Joffrey Ballet School summer intensives in Los Angeles and San Francisco, had her heart set on becoming a ballet dancer. But as a 16-year-old student, she was diagnosed with two fractured vertebrae in her lumbar spine; she had to wear a plaster cast for 23 hours a day for nearly four months. Her doctor told her she would never become a professional dancer.

But for Walsh, there was no plan B. Instead of giving up, she decided to prove she could still do it. “I didn’t get fearful,” says Walsh, “I got determined.”

Unable to go to the studio, she started visualizing class in her head; she was also treated with acupuncture. After three and a half months, she began physical therapy and was allowed to go back to class a few weeks later, after an MRI showed she had recovered completely. Walsh went on to dance with the Joffrey Ballet, Oregon Ballet Theatre, and in Europe before founding her own contemporary dance company, BalletRED.

Lumbar fractures can have significant effects on a dancer’s career, but with proper treatment and rehabilitation, they don’t have to be career-ending. Here’s what you need to know about this tricky injury.

How Common Are Back Fractures?

More than 70 percent of dancers experience lower back pain, according to a report in the Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. Problems range from sprains and spasms to disc degeneration and spinal fractures. Some studies have found that the spine is among the most commonly injured part of the body in dancers, second only to the feet and ankles.

One of the main culprits of fractures of the lumbar spine is faulty technique. “A young dancer can increase the turnout of the hip by swaying their lower back,” says Dr. Lyle Micheli, Boston Ballet’s emeritus attending physician, who served as the company’s primary attending physician from 1974 to 2016. “But the danger is if it becomes a habit.” Arching the back while dancing can result in spinal injury down the road, he explains, as it puts excessive pressure on the spine.

Extreme movements, such as huge backbends, can be another cause when done incorrectly. “A body is like a bicycle chain, and every joint represents a link,” explains Itamar Stern, a physical therapist based in Phoenix, Arizona, with a specialty in dance. The spine—the skeleton’s central link—connects to bones above and below it, so poor technique in both the upper and lower body can affect the vertebrae of the lower back.

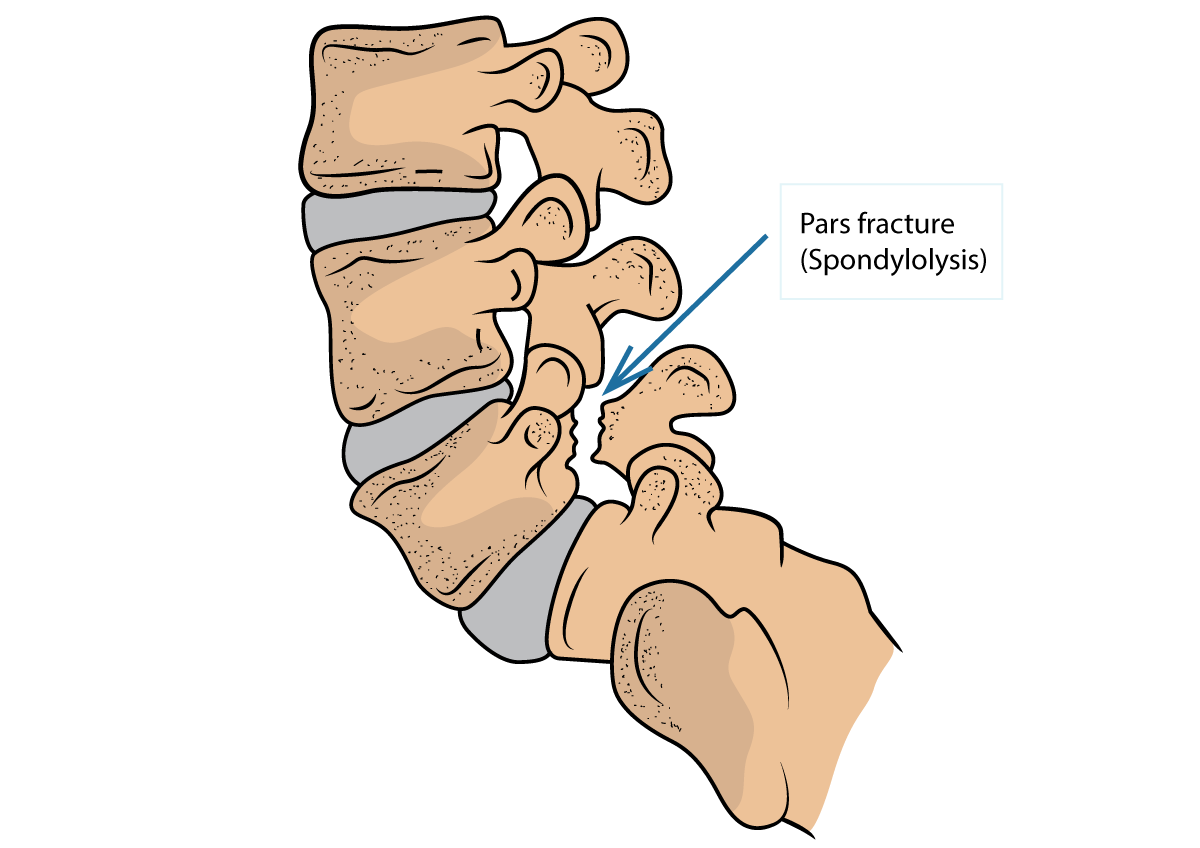

According to Stern, young female dancers tend to have more back issues than males due to high mobility and poor stability. Stress fractures of the lumbar spine (spondylolysis) are more common in women, says Micheli, while disc problems tend to be more common in male ballet dancers due to faulty partnering technique. Lumbar fractures usually occur independently of disc injuries.

Warning Signs

Aches and pains are so common in dance that it can be difficult to know when pain or discomfort indicates a more serious problem.

Sage Humphries, a second soloist with Boston Ballet, had just begun rehearsing for the company’s first season program when she developed back pain. “It felt like I had a knot that wouldn’t release,” she says. But an MRI taken by her physical therapist that fall revealed the “knot” to be spondylolysis.

Humphries found the pain in her right mid-back nagging and relentless, a kind of sensation that was difficult to distinguish between deep bone pain and regular soreness. She was struck with fear when she was told she had a back fracture—and that she had to stop dancing immediately. She was sidelined for the rest of the season.

Spinal injuries don’t always cause major symptoms, as Humphries learned. But knowing the warning signs of a back fracture, and seeking the advice of a dance medicine professional, can help speed healing and prevent future injuries.

Aligning the Spine

Micheli urges dancers to work closely with a physician specialized in dance medicine for both diagnosis and treatment of spinal fractures. Surgery is rarely necessary, but rest from physical activity, along with rehabilitation and, sometimes, bracing, may be.

To recover fully, Humphries began working with ballet rehabilitation specialist Alicia Head. She started with physical therapy exercises and gradually built up to performing ballet steps. “We spent hours at the barre, breaking down a simple plié,” says Humphries. Discovering how to move with better alignment made her stronger and more confident.

Walsh says her injury turned out to be a blessing because it taught her about the power of the mind and the effectiveness of visualization. Starting with pirouettes, she eventually built up to visualizing an entire 90-minute class, finding that her turns improved as a result. During the recovery process, she’d also spend 90 minutes a day visualizing her back healing. “I didn’t have access to my body, but I did have access to my mind,” she says.

Both Walsh and Humphries say the experience of having a spinal fracture made them aware of prioritizing alignment first and foremost. “If you are not in alignment, you are vulnerable,” says Walsh. When she teaches at summer intensives, Humphries says the largest part of her class is devoted to the barre to focus on alignment, knowing her students will return to a typical pace in their other classes: “Oftentimes I’m just planting a seed.”

Proactive Prevention

Dancers tend to push through pain, but it’s crucial to be alert to warning signs so you can catch a spinal fracture early and prevent its progression.

“If your pain doesn’t go away with whatever has worked for you in the past—whether it be ice or Advil for three days—then that’s a red light,” says Stern. Pain that occurs only in a backbend but not with forward bending is another sign, says Micheli.

Take a proactive approach by integrating strength training into your routine. As part of her recovery and for overall conditioning, Humphries now does cross-training, Pilates, and Gyrotonic regularly. Stern also emphasizes that dancers need to eat a balanced diet that includes nutrients that support bone health, such as calcium and vitamin D.

It’s important to learn to recognize when you have an unusual level of discomfort and which movements cause it, Stern advises. Don’t wait more than two weeks to consult a doctor, physical therapist, or other medical professional for an evaluation.

Change Your Dancing From the Inside Out

If you do end up having to take a hiatus, Humphries advises using the time to dive deeper into your technique. An injury, she says, can be an opportunity to change your dancing “from the inside out.”

Walsh says she now sees her injury as a blessing. “It taught me an incredible amount about the mind,” she says. “Visualization isn’t nonphysical. It’s firing up the muscles. It’s rewiring and reprogramming the brain. Once I understood that, there was nothing I couldn’t do.”

Humphries says her spine will always be her Achilles heel. But in a recent performance of the “Kingdom of the Shades” scene from La Bayadère, she was the first dancer in the long line of ballerinas and did 38 arabesque penchées per show.“That moment going down the ramp, I was relying on five years of maintaining back health,” she says. “I felt like it was the most important arabesque of my life.”