Catherine Devillier: Ballet’s Pioneering Black Russian and LGBTQ+ Soloist

In a March 1959 obituary, Dancing Times described the Russian-born Black ballerina Catherine Devillier as “one of the great teachers of character dancing in recent years.” Her career began with her appointment as principal character dancer at the Bolshoi Theatre soon after graduation from The Imperial Moscow Theatre School in 1908. Devillier’s resumé was peppered with impressive accomplishments, including touring with Anna Pavlova during the Bolshoi’s summer breaks, performing as one of the lead swans in Swan Lake during Olga Preobrajenska’s 1910 London tour, and dancing with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes from 1920 to 1921.

Though Devillier’s achievements have received relatively little recognition, she has become a research interest of the ballet historian Sergey Konaev, who is currently a visiting scholar at the University of Texas at Austin. In 2021, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’ News From the Jerome Robbins Foundation published Konaev’s article, “Teaching to Survive: Catherine Devillier Black History in Dance. Russian contribution.” In it, he writes that Devillier was not “stigmatized” for her skin color, but praised for “the softness of her dance, her ardor, her chic, her musicianship, and her kind eyes,” and compared at times to Josephine Baker. Perhaps most significantly, Konaev notes that Devillier was possibly “the first Black principal ballet soloist,” referring not to her official rank but to her importance to the Bolshoi and choreographer Alexander Gorsky, as well as the number and variety of her performances.

According to Konaev, Devillier’s repertory exceeded that of Maria Skorsiuk—the Imperial Russian Ballet’s first known Black ballerina, who died in 1901—and included a leading role, Norwegian Fisherwoman, in Gorsky’s Love is Fast, to composer Edvard Grieg’s Norwegian Dances. Konaev also found a record of Devillier as a lead soloist in Hungarian Rhapsody shortly before her departure from czarist Russia following the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. “With more than 70 performances each season, Devillier was an important part of Bolshoi creativity,” says Konaev. “In the official ranks of the Imperial Theatres, her last known position is ‘second grade artist,’ with a 1400-rouble salary per annum—close to the highest. There were four grades in total, with first as the highest.”

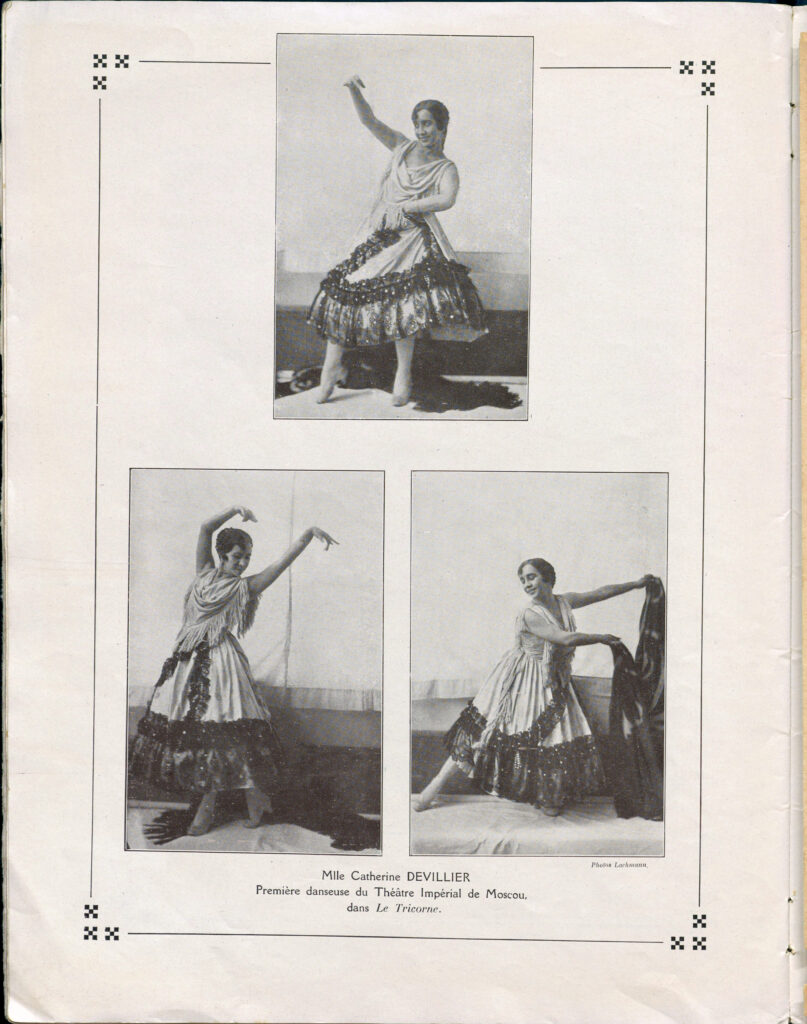

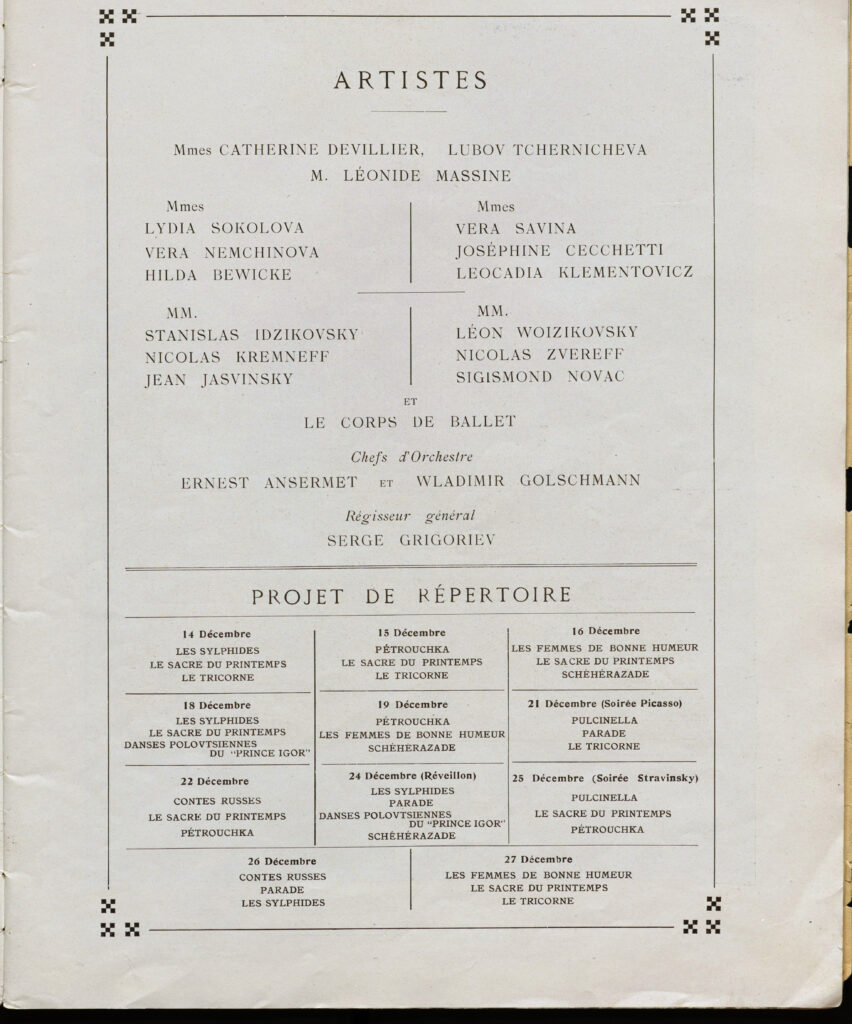

Devillier’s tenure in the Ballets Russes began upon her arrival in London circa 1920. With Diaghilev’s company, she danced several noteworthy roles, including the Chosen One in Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring and, what Dancing Times called her “greatest part,” the Miller’s Wife in Massine’s Le Tricorne, which she danced in a gala performance before the King of Spain. Devillier also worked as a choreographer in London, Berlin, and Paris, and arranged dance sequences in films, her last work being on the ballroom scenes in Anastasia (1956).

Devillier also taught at London’s Royal Academy of Dancing. “Devillier’s method of teaching reflected her own approach to expression, shaped and encouraged by Gorsky and the Moscow traditions, which prioritized dramatic effects and theatricalization,” Konaev says.

In full view is Devillier’s impact both as a dancer and a teacher. However, what we did not know is just as—if not more—enticing than what we do. In February 2021, Konaev’s research prompted former New York Times critic Alastair Macaulay to post online a breathless acknowledgment that his own “view of dance was largely white and largely Eurocentric” until this intervention that enhances the history of both the Black and LGBTQ+ presences in ballet.

Konaev asserts that Devillier is a history-making Black ballerina who “remains underestimated, and her contribution to the development of the British ballet is almost forgotten by dance historians—including those who have a focus on female, Black and queer creators,” according to his article. To begin the exploration, Konaev details a biography that includes parents who never wed, including a Black father—likely a French citizen named Ludwig Devillier—and the eminent theatrical actress Vera Popova-Vasillieva, who was part of the Vasillievs Imperial Maly Theater dynasty.

Among the numerous ballets, operas, and plays Devillier performed in with the ballet company of the Imperial Moscow Theatres (which became the Bolshoi Ballet), according to the 1908–09 Yearbook of the Imperial Theatres, is the role of Aya in Gorsky’s La Bayadère. In fact, Konaev discovered Devillier thanks to the dancer Maria Gorshkova’s account of Devillier’s tearful objection to wearing white powder makeup in the “Dance of the Hours” in Coppélia’s third act. According to Gorshkova, “Katya [her nickname] despised this dance” because of the makeup, and when her pleas to be exempt from it were refused, she appealed to Gorsky. Gorshkova also reports that Gorsky at first laughingly dismissed Devillier’s complaints about how much powder she needed to make herself appear white, but he was so moved when she cried about it that he gave in. Following the incident, Devillier was awarded principal roles and became a prominent soloist.

Ironically, although Konaev insists both in his article and during our interview that Devillier was not “stigmatized” because of her skin color, he writes that, in the Imperial Theatres, she “specialized in exotic and enslaved characters like Gulnare in Le Corsaire, Aya in La Bayadère, Shakh’s Wife in The Little Humpbacked Horse—not to mention the Spanish, Persian, and other ‘wild’ and oriental dances seen in Swan Lake, Raymonda, Nutcracker, and 19th-century grand operas.” Most of her roles fit the description of what the renowned postcolonial culture theorist Edward Said (1935–2003) identifies as false, romanticized representations of the non–Western European Other in his celebrated study, Orientalism.

Konaev also notes in his NYPL article that, while Devillier was married twice, she later fell in love with Princess Dilkusha de Rohan in Berlin and became her life partner. The couple’s social circle included the noted Diaghilev and Balanchine collaborator, painter, and set designer Pavel Tchelitchew, along with Anna Pavlova, literary great Gertrude Stein and her life-partner Alice B. Toklas, and others who are partially documented in the letters in the archives at the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas.

The Dancing Times’ obit says, “Mme Devillier will be remembered not only as a dancer and teacher, but as a person whose great charm, wit, kindness and modesty endeared her to all who knew her.” Now, thanks to passionate researchers, she will also be remembered as a notable Black ballerina.