Finding a Forgotten Black Ballerina: Maria Skorsiuk

History’s rare gems often languish in the shadows of what might have been, and ballet is no exception. Those credited with shaping the artform—usually choreographers, principal dancers and impresarios—become legends, while corps de ballet members mostly go unrecognized. In 1890, a young dancer named Maria Skorsiuk entered the Imperial Russian Ballet. With her allure, stage presence and passionate dancing, she could have potentially influenced future generations. Skorsiuk is believed to have been the company’s first Black ballerina.

Born in St. Petersburg in 1872 and possessing African and Russian lineage, Skorsiuk likely descended from the Moors of the Russian court: paid Black servants of royalty. Moors were part of court life from the late 17th to early 20th centuries, initially serving as amusements. Under Peter the Great, they came to be treated less as exotic curiosities, receiving opportunities for serious education and more influential positions. A widely known example is General Abram Petrovitch Gannibal, great-grandfather of the poet Alexander Pushkin. Skorsiuk’s parentage remains a mystery, though her father was from Luga, Russia, and belonged to the lower urban class.

“Even in an old and grainy picture, I saw how she was very expressive, and I thought, Whoa, who are you?”

—Peter Koppers, ballet historian

Peter Koppers, a dance scholar and former member of the Dutch National Ballet, came across her while researching the Imperial Russian Ballet. As a Black ballet dancer himself, Koppers was intrigued. “Shortly after [first learning of her], I saw a photo of her and I was stunned by her beauty,” he says. “Even in an old and grainy picture, I saw how she was very expressive, and I thought, Whoa, who are you?” Most of his findings are available in an online profile published by The Marius Petipa Society.

After Skorsiuk’s spring exams in 1888, she faced expulsion from the Imperial Theatre School due to vague claims of unsuitability from theater officials. Her teacher, Ekaterina Vazem, fought for a second test and later recommended the young dancer to Marius Petipa, the premier maître de ballet of the Imperial Theatres, which helped to launch Skorsiuk’s career.

Skorsiuk was highly regarded for her character dancing, but also performed on pointe. In her final year as a student, she performed in the world premiere of The Sleeping Beauty. Yet her signature roles came to be Raymonda’s Saracen duet—which Petipa created on her and Alexander Gorsky—and Swan Lake’s Spanish dance. She also appeared in Cinderella and revivals of Coppélia, Le Corsaire and The Little Humpbacked Horse, and danced prominent parts in several now-forgotten ballets. She performed with the company as a corps de ballet dancer for 10 years—achieving the rank of coryphée—while battling tuberculosis, which she died from in 1901.

Pointe spoke with Peter Koppers about Skorsiuk’s life and career.

Can you talk a bit about the ballets she danced in and having roles created on her by Petipa? What was the creative process like?

Looking at the roles she danced that are still in the active classical repertory of today’s companies, you have The Sleeping Beauty. She danced the part that we now call ‘Aurora’s friends’—the eight girls accompanying Aurora in the Rose Adagio. That used to be four ladies of honor and four smaller girls. In Western companies, that’s combined now. But in the Mariinsky production, you still see that division between four bigger girls and four smaller girls. She was one of the smaller girls because they were originated by the best pupils of the school.

People in the company must have noticed her then, because when she joined the company, she started to get smaller roles in ballets—alas, ballets that are forgotten now.

She also did—an important part—the Mirlitons in The Nutcracker, which is a hard number for about six girls. The original version was a bit like Balanchine’s in the New York City Ballet version. There are lots of jumps.

Other important roles include the Spanish dance in Swan Lake, and the Saracen dance in Raymonda. I think, with the performance she gave, she was much more expressive than the white ladies who were given the character parts. I think a lot of her stylistic influence continued through Alexander Shiryaev, who danced with her occasionally. Theirs was not a hugely interesting partnership, but he admired her as a colleague.

He became assistant ballet master of the Imperial Ballet in 1900—when Skorsiuk was already ill with tuberculosis, so she did not dance in his stagings—and taught character classes for the school for some years starting in 1905. After a long hiatus, he took it up again in 1918. So, I think a lot of the dynamics, the pizzazz of her dancing, entered through Shiryaev into the school of today. For example, this pertains to Corsaire’s Forban dance and the Saracen dance in Raymonda, which ends in a huge backbend, though Gorsky supported her solely by her head, which is lost in modern stagings. The partner supports the girl by the waist now.

Her influence also applies more generally, to when the “Oriental and Spanish” curriculum of the character school was conceived. By the time the [Imperial] Theatre School—now Vaganova Academy—had this in place, many of the ballets in which Skorsiuk had roles were no longer performed. But her style continued to inspire Shiryaev’s exercises.

The original choreography that she danced for Swan Lake‘s Spanish dance and Raymonda‘s Saracen dance still exists in some form, then?

Yes, the Saracen dance has not really changed that much.

Some of the other ballets that she was featured prominently in, like Mlada and The Pearl, are completely lost to history, as far as we know.

Unfortunately, yes. She also had a big role in the ballet The Mikado’s Daughter, which was a Japanese fantasy of Lev Ivanov, the choreographer of Swan Lake’s white act. We could have had a more complete picture of her if those ballets had not been lost.

I’m curious about the role that stereotyping or prejudice may have played because of the time period, which you also discussed in your piece for the Petipa Society. Could you talk a bit more about that? Did experts’ opinions of her technical weakness seem clouded by any sort of bias?

That is hard to say. Of course, it was a different time. Ekaterina Vazem, who was her teacher in the school, really fought for her to get into the company. That was a brave act in itself in those days. But then again, I also posed the question in the article of whether she could have done more pointework—more classical roles—if she had not been Black, because to a certain extent, she was typecast.

In the end, I went with Shiryaev[‘s assessment], because he said her technique wasn’t that strong. The emphasis of today is so much on technique, turnout and pirouettes, and in those days, I think her promotion within the company testifies that they were more about artistry than technique for its own sake. But then again, because she was cast in the Mirlitons, for which you need good classical technique, you can also adopt the view, “If she was successful in that, why didn’t she get more of it?” So it’s a bit of both, actually.

Where do you suspect Skorsiuk’s career might have gone, had she not gotten tuberculosis and died so young?

With her talent—also, her specific talent for character dances—she would have been a great successor to Marie Petipa, Marius Petipa’s eldest daughter, who danced mainly character parts. Marie had weak classical technique, but had many fans and appeared in magazines. She had a lot of roles, many of them created on her—Lilac Fairy, first and foremost. Skorsiuk could have been extremely well suited to many of her parts.

Skorsiuk would have been a role model and example. Maybe Diaghilev even would have hired her. Had she lived, she could have made a great Cleopatra and Zobeide in Scheherazade for Diaghilev, among other less typecast roles, although she would have been around 40 then. But dancers danced on longer back then. Think of what she could have meant for The Ballets Russes, and dancing in all those modern ballets. It’s one of the big ifs for me.

Is there anything else that you want to share about her?

When you research and write about someone, you kind of fall in love with that person, and I certainly did with her. Even after all those years of being semi-forgotten, she still had the power to mesmerize me.

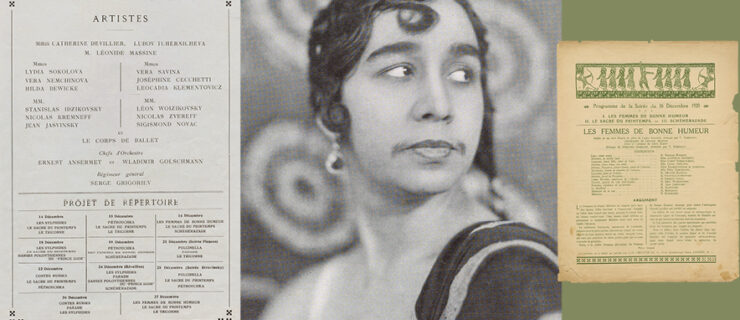

Header photo credits, clockwise from top left: Portrait of Maria Skorsiuk, photographer unknown; costume design by Evgeny Ponomarev for Jalousie in La Vestale (1888), a role Skorsiuk performed; portrait of Skorsiuk, photographer unknown (c. 1890); set design by Vasily Vasiliev for Le Roi Candaule Act I, Scene II (1891); La Peltata in Le Roi Candaule (1891), which Skorsiuk danced; Skorsiuk as Morena in Mlada (1897); costume design by Ivan Vsevolozhsky for a shell fighter in The Pearl (1896), a role of Skorsiuk’s; Skorsiuk in the Saracen dance from Raymonda with Alexander Gorsky (1898); group of The Sleeping Beauty Act I, with Skorsiuk at left, Felix Kschessinsky second from left, Carlotta Brianza second from right, Iosefina Cecchètti at right (1890); portrait by an unknown photographer in an unidentified role; Imperial Russian Theatre School graduation class (1890); Swan Lake program with Skorsiuk listed in the Spanish dance (1895). Photos: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music, courtesy Peter Koppers