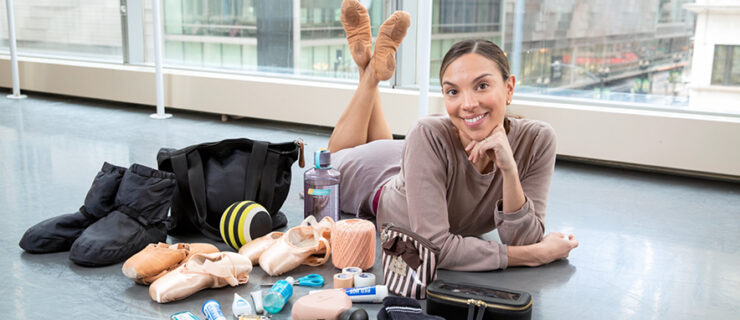

Chyrstyn Mariah Fentroy’s Advice for Keeping a Positive Mindset, and Why She Deeply Investigates Each Role

An engaging powerhouse, Boston Ballet principal Chyrstyn Mariah Fentroy is always looking for ways to dig deeper in her work. She brings the same passion for investigation to the role of Kitri as she does to William Forsythe ballets—demonstrating her point that with the right mindset and continuous hard work, a dancer is capable of remarkable things.

You didn’t pursue ballet seriously until you were 18 and at your first summer intensive. What drew you in at that point?

I fell in love with the rigor of ballet—wanting to get up for it every morning and coming home exhausted. I was always working for something—achievable or not, there was always something.

Your mother was a dancer. How has that influenced you?

I really started to appreciate having a former ballerina as my mom later in life. I always have someone I can turn to when I’m struggling with something, whether it’s an approach to a character, a step I’m not getting, or the highs and lows you go through as a professional dancer. I understand how helpful it is to have someone in your life who’s gone through those emotions.

What is it like to have her in the audience?

It adds both pressure and support to performances. Naturally there’s my internal pressure of wanting to succeed for her, but I also want to recognize how much she gave up in her career for me to have mine—it’s not easy to be a parent in dance. I want so much to honor her career in my own.

What do you enjoy more: performing or being in the studio?

I love performing. I get more nervous when I have to do a run-through in the studio than onstage. There’s something about those moments you have with people onstage that you can’t duplicate or get back. They’re very real, very special, and very limited in our career.

Which do you enjoy more—telling full-length story ballets or plotless, neoclassical works?

Both, for different reasons. Forsythe will always feel like home for me. I love the feeling of having my lungs burn, my legs tingle, and pushing myself to do something more and something different. I can always dig deeper—that level of exploration is something I’m always hungry for. In that way, it comes more naturally to me. But I’ve also always wanted to tell a story onstage, to go from beginning to end with the responsibility of taking the audience with you. Classical ballet can be more challenging for me because I’m an incredibly impulsive dancer, and I have a hard time reeling that in sometimes.

What’s your pre-performance routine?

I’m a creature of habit. I stand at the same barre spot at the theater. I almost always nap before a performance. And I always put lavender oil on my wrists and neck right before I go onstage, for two reasons: It’s calming and smells nice, and because of my mom—she used to wear it when I was a kid.

What role taught you the most about yourself as a dancer?

I danced a duet called When Love, by Helen Pickett, with my now fiancé early in my career at Dance Theatre of Harlem. Her approach pulled more from me—wanting more generous movement and tapping into real human emotion, while also being very demanding about being true to ballet technique. It was one of the first times I allowed myself to genuinely try things; not only do what was asked, but search for more. That’s when my hunger for investigation in my performances really started, when I fell in love with being really present onstage.

If you weren’t a dancer, what would you be?

My answer changes all the time. Most recently it would be working in a flower shop or in flower arrangement. I love flowers—how they look, how they smell. I love the idea of being able to give somebody a different kind of flower depending on what they’re going through. I just want to play in the flowers.

Do you have a secret talent?

I’m super-crafty. I like to buy things like jean jackets from thrift shops, then embroider the backs. I wear them around and then people ask me where I got them.

What advice would you have for students wanting to be professional dancers?

Your mind has a lot of strengths; it’s just like any other muscle in the body. When you believe in yourself and tell yourself that you can—it’s not about being arrogant, but about really believing that the work that you’re putting in will show—it does show. You may not see it immediately, but if you keep pushing, it can and will happen. Your body reacts to what your mind is telling you.

How do you work through the extreme perfectionism so many dancers suffer from?

I don’t know if that voice ever leaves. I had a teacher in school once who said, “Nobody wants to work with an angry dancer.” The more I chewed on it, I understood what they were saying—when someone’s in a cranky mood, you don’t even want to go up to them. I started to work on not being so reactive to my emotions. I can still feel what I feel, but not hate myself because I fell out of one pirouette. Once I learned how to laugh at myself and my mistakes, I was able to recover faster and learn more from them. When I approached dance with a more positive mindset, my body reacted better. We all have bad days, but I’m getting better at recognizing that it’s just a day, and there’s tomorrow, and look at how far I have come.