They Called It Macaroni: Loughlan Prior Showcases Queer History at BalletX

Macaroni. Wigs. Camp. Ballet.

Loughlan Prior’s world premiere for BalletX, debuting in the company’s Summer Series 2024 program July 10–21, promises all this and more. For this unabashedly flamboyant new work, the Royal New Zealand Ballet resident choreographer dives into caricature—and reclaims it.

Macaroni, which takes its name from the 18th-century derogatory slang referring to queer or dandyish men, will run alongside two other world premieres, by Stina Quagebeur and Amy Hall Garner, in the Summer Series program. Prior’s work features an original score by Kiwi composer and frequent collaborator Claire Cowan, as well as costume design by Emma Kingsbury.

“A lot of my work recently has focused on queer activism,” said Prior in an interview with Pointe, explaining that he traces his idea for Macaroni back to the 2019 Met Gala and its “Camp” theme. “It piqued my interest around camp fashion, and that’s how I discovered the macaroni.”

A small ensemble piece for eight dancers, the 24-minute abstract ballet is divided into seven sections. And while the work takes some inspiration from 18th-century court cases criminalizing same-sex activity, it does not follow a strict narrative. Nor does it dwell on the homophobia that made such jurisdictions possible.

“We wanted to create more of a celebration of Pride,” said Prior. “Something really uplifting that reclaims that discrimination, or the ways these people were satirized by the community.”

Here, he shares more.

After you got the idea for Macaroni, how did you go about researching for and framing the ballet?

When I go into a project, I do a deep dive. I wanted to know more about these people who predated the dandy, which is probably what we most associate with flamboyancy and “pretty gentlemen.” They were the predecessors, or forefathers, of that era. So very much looking at the sartorial history and the elaborate fashions. The movement style is very gestural, and there’s a lot of over-the-top, slapstick movement language between the dancers. I’m trying to re-create, in a way, what those people might have been like.

And the name “Macaroni” I thought was hilarious. In our modern vernacular, of course, we just associate it with the pasta. But back then, it was the British looking at Europeans with a xenophobic, queerphobic gaze; anyone who was different or flamboyant was called a macaroni. [Macaronis were known to prefer “daintier” foods, like pasta, over traditional English cuisine.] It’s also interesting how the name found its way into Americana culture, and into one of the most patriotic American anthems [“Yankee Doodle”].

How would you describe Claire Cowen’s score?

The music is an original composition. It uses a lot of traditional instruments from the period, like the harpsichord and classical flute, but there’s also a beat in there, and it gets kinda funky. We’ve used a lot of voiceover text, as well. The voice is AI-generated; we wanted to find a voice that was a caricature, and computer-generated voices have that weird, nonperson quality. It’s actually Claire’s voice run through a program, which changes the timbre and quality into a more posh, flamboyant tone.

Basically, it’s a mélange of different parts—which, in essence, is macaroni. Because their language was “more is more,” and the higher the wig, the better.

Speaking of wigs, what are the sets and costumes like?

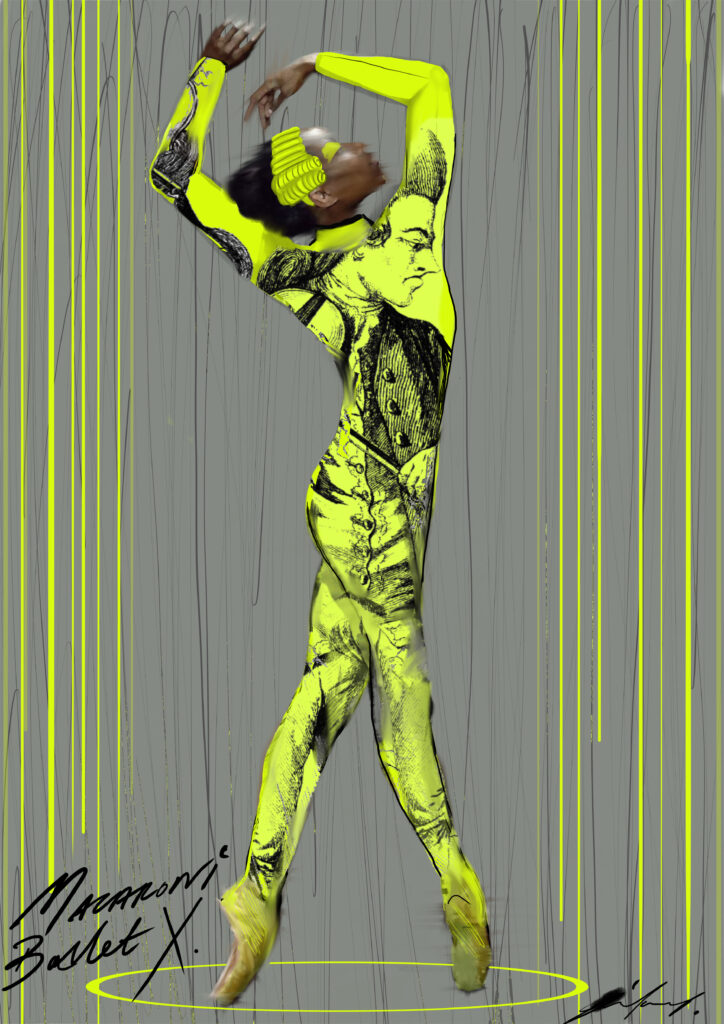

I’ve worked very closely with our designer, Emma Kingsbury, to create a look that would be the modern macaroni. I’m kind of obsessed with the color citron, and if you look back, historically, it’s around the time that badminton and tennis were being popularized in the courts. So we took that color and ran with it as our dominant color, set against black. It’s a neon pop with a more historical silhouette.

Emma has also taken prints—these were some of the first types of cartoons—of the macaronis made to satirize them. A shop in New York has printed them onto fabric, which will be made into unitards. The dancers are essentially wearing larger-than-life cartoon satires of themselves. It’s very meta. Everyone has a citron-colored wig made of hard fabric, and then there are little tricorn hats with giant feathers they’ll attach. (We’ve actually used the feather a lot as a choreographic tool. It’s very versatile—there’s a lot of tickling involved.)

Your first piece for BalletX was a pandemic-era film choreographed over Zoom. How has it been working with the company now on Macaroni?

It’s been fantastic. Everyone’s so receptive, and they’re really open to collaborating and using their own voices within the themes. I’m so grateful for that because when you are creating something that is special like this and has a lot of humor, you can’t do it in a vacuum. You need input from everybody. I love watching the work keep getting piled on and onto, just like a giant macaroni wig.

What are your thoughts on presenting this somewhat historical niche as a ballet?

Sometimes the “undesirables” in history are buried. It is fascinating that not a lot of people know about this particular period because it’s very present in today’s queer culture. Drag queens, for example. The celebration of being who you are, and those liberties, are not taken for granted now, but we’re still fighting for the right to be ourselves, hundreds of years after the macaronis.

Camp, femme, queer—all of that is still very much in the vernacular. And you can include the macaroni alongside it. It’s a love letter, this piece, to camp and being authentically yourself.