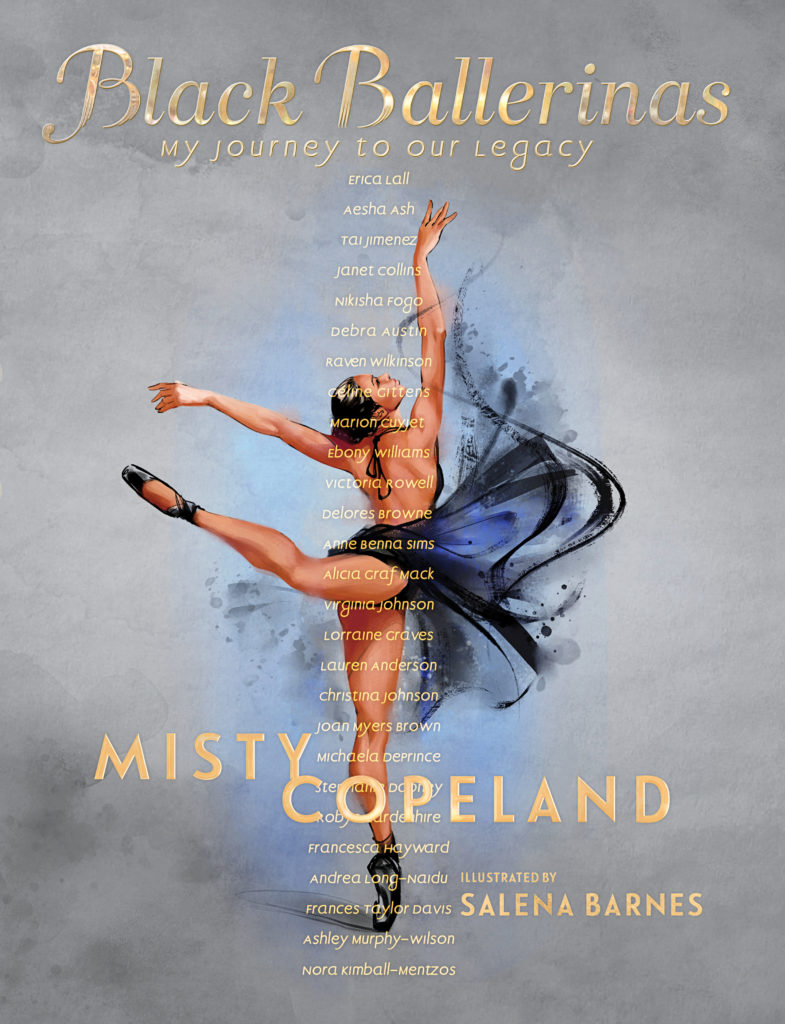

Misty Copeland on Her New Book, “Black Ballerinas”

In 1999, a 17-year-old Misty Copeland noticed an image that would help shape her future: Lauren Anderson, the first Black principal dancer with Houston Ballet, on the cover of Dance Magazine. Copeland, then a pre-professional ballet student, was awestruck. “It was an anomaly to see her beauty in all its glory representing the very white and exclusive ballet world,” she writes in Black Ballerinas: My Journey to Our Legacy (Simon & Schuster, $19.99), the new middle-grade book honoring her counterparts from the past and present. “It would change everything for me.”

Since then, Copeland has not only become American Ballet Theatre’s first Black female principal; she has dedicated herself to championing diversity in ballet and celebrating its unsung heroes of color.

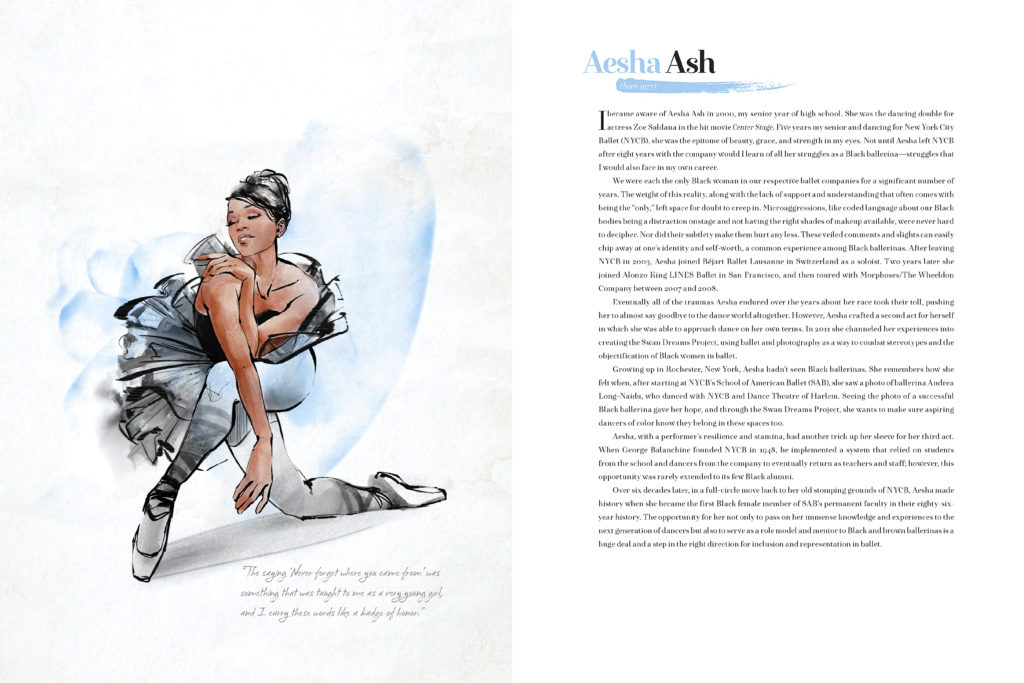

She had wanted to write Black Ballerinas for over a decade. It came together during the pandemic, in just over a year and a half. The book details Copeland’s personal and historical connections to 27 other groundbreaking Black women in ballet, including Aesha Ash, Michaela DePrince and Virginia Johnson. Berlin-based artist Salena Barnes, whose work focuses on Black people and people of color, provided illustration.

Copeland’s previous books—Life in Motion, Bunheads, Firebird and Ballerina Body—similarly reflect her story and the transformative power of community, mentorship and service. Now, she shines a spotlight on those who too often remain in the shadows.

Pointe spoke with Copeland about how it felt to write Black Ballerinas—due out on November 2—and her advice for young dancers who want to make a difference.

Can you take us through the creative process?

It was important for me to not just list facts about each dancer, but to say something a little more personal about how they’ve impacted my life and the ballet world.

Once we had the concept and the format, it just took a little bit of finessing. It was [a matter of] deciding which ballerinas I wanted. There are mornings when I wake up, and I’m like, “Why didn’t I include this person?”

I’d initially selected 26 ballerinas, then I added Marion Cuyjet to the list. Through all of my research, it just didn’t feel right not to include her, because she is such a vital part of so many ballerinas’ starts and a central force of so many of these legacies.

I hope that people will read Frances Taylor Davis‘ profile in particular. On her deathbed, we were having conversations about finding the playbill from the time she guested with the Paris Opéra Ballet in a gala. She danced Swan Lake as the first Black woman onstage with that company. I’ve never been able to find any documentation of that, and neither did she. It was her last wish for me. That would be an incredible mission for other people to help with.

You’ve written several books before. What was the experience of writing this one like, emotionally?

It was extremely emotional and frustrating. It’s such a tough process to revisit situations or go back in history and relive injustices, and so much of this book is that. It’s not only celebrating the incredible women and what they accomplished—in really trying times, for a lot of them—but also acknowledging how deeply unfair so many of these journeys have been.

I’ve always felt that part of my purpose was to tell the stories of other Black dancers who have allowed me to be in this space, and of other dancers who are going to continue on after me. But it’s a lot of pressure. I feel like people are looking to me—it’s never going to be perfect. There’s a lot of anxiety going into writing this—into making sure that I get it just right, and that people understand that I am telling these women’s stories through my lens.

If you’d had a book like Black Ballerinas when you were first getting interested in ballet, what do you think the effect would have been?

I get emotional just thinking about it. I think I would have been more prepared for what was to come. I’m grateful for my path, because when I was brought into the ballet world at 13 years old, I was really protected. I wasn’t taught about Black dancers, but I also wasn’t told, “You are going to have a tough time and you don’t belong in this space.” So I went into American Ballet Theatre feeling, in a lot of ways, like the other dancers, like I didn’t have something that was working against me. I was very aware that I was a Black girl in the world, but when it came to ballet, I felt like I was in this magical world where none of that experience outside existed. It was a beautiful fantasy.

If I’d had this book, though, I think the professional world wouldn’t have been such a shock. And I probably wouldn’t have had so many ups and downs and doubt. [These dancers] gave me the push to stay motivated and keep going. Some of them lived in a time when I can’t imagine being Black and persevering and making an impact. I would have been inspired, I think, earlier on in my career, and maybe wouldn’t have been so hard on myself.

What impact do you want this book to have on the next generation?

I want it to motivate them to contribute as well. And I don’t think this is just for Black dancers or Black girls. I think that this can inspire others to do their own research, not just on this amazing legacy of Black ballerinas, but also within their own culture. I think that, especially as Americans, it’s important for us to know our whole history to understand other people and who we are.

In the future, if you were to meet a nondancer who had read this as a child, what takeaways would you want them to have from it?

I’d want them to understand the hard work and sacrifice that goes into being a part of this world, not just as a dancer, but as a dancer of color. People who are not minorities might not understand the idea that people of color or Black people have to work 10 times harder. But maybe reading this book will show them that when we say “working,” it’s not just about the sweat equity that we’re putting into something. It’s all of the work that goes around it of being Black, or someone of color, day in and day out—the things you have to deal with, and existing in a world where you feel othered.

The artwork in this book is striking. How did it unfold?

Salena Barnes’ work stood out immediately to me for the beauty and richness in which she shapes people and characters. It takes real talent to draw the proportions and lines of a dancer, especially if you’re not one, and what she did brought this book to life in such a beautiful way.

In recent years, more young people in ballet have begun to recognize their own beauty and value, and speak up about the changes that they want to see. What’s your advice to those who want to advocate for progress in their home studio or community, but are unsure of how to do it?

It’s important to make people feel that it’s inclusive, and not combative, and that we’re not preaching. You want it to be a two-way conversation, and you don’t want to be talking at people. If there are people of color within your studio, allow them to speak and share their stories, and then create a dialogue to figure out how you can be an ally, or how you can move forward and make progress. But listening is the first step.

Shortly after the George Floyd uprising, you mentioned feeling like more people in ballet were listening to the conversations about diversity that have been happening for so many years. More than a year later, what are your thoughts on the effect of that movement on ballet?

It’s been incredible. What’s happened in the last year and a half is the most movement I’ve seen in all of my career. It’s been pretty impressive to see such change in a really short, concentrated period of time because of this racial reckoning within the world.

I recently watched Calvin Royal III make his debut as Albrecht at ABT. And for my entire career, there have been a lot of discussions about whether Black dancers should wear tights that represented their skin color. To see [corps member] Erica Lall onstage in Giselle, wearing tights that were her color, was huge progress. I felt like I saw her as a person the way that every other dancer is allowed to be seen as an individual, even if they’re in the corps de ballet.

At ABT, we’ve had talks about diversity initiatives and bringing in more people of color, not just within the company but in other areas of the institution, and to see it happening is huge. Now, it’s everyone’s responsibility to keep it moving, and not to settle in this moment. I think next is tackling the stories that we’re telling onstage, especially here in America. They need to be relevant and [show] that there’s more than one type of person.