Netflix’s “Tiny Pretty Things” Faces Ballet Stereotypes Head-On

The pilot of Netflix’s dance-centric series “Tiny Pretty Things”—based on the YA novel by Sona Charaipotra and Dhonielle Clayton—will leave you breathless. It touches on, well, everything: love, murder, racism, competition, jealousy, girl cliques, sexual experimentation, eating disorders. And the intricate plot is propelled by equally breathtaking ballet sequences.

Here are the basics of that plot: The Archer School of Ballet is the premiere conservatory in Chicago. During the first three minutes of the episode (no spoilers!), star student Cassie Shore is pirouetting along the edge of the roof of the school when she’s pushed off by a hooded man (Her boyfriend? A jealous lover? A ballet master or choreographer?) and dies. Neveah Stroyer, who’d previously been rejected from the school, is flown in from L.A. to replace her.

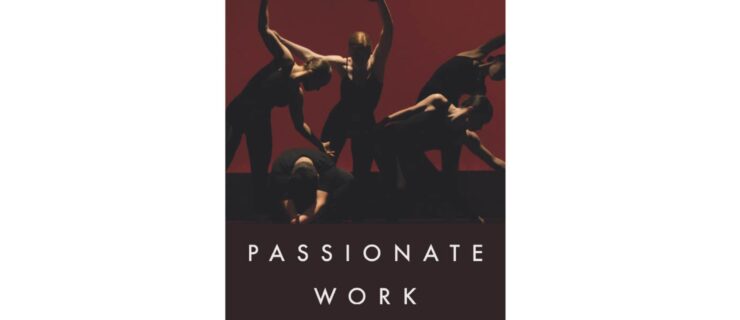

While the series can verge on melodrama—the pilot does open with a dancer being pushed off a roof, after all—its depiction of the finer details of the ballet world feels spot-on. That was paramount to the production team. “We wanted the dancers to feel represented in their athleticism, and in the sometimes ugly business of making something beautiful,” says executive producer Jordanna Fraiberg. “The show encompasses the grit and sweat, before it’s wrapped up in costumes and makeup.”

Catch “Tiny Pretty Things” streaming on Netflix Monday, December 14.

Finding the Right Cast

To ensure the show would feel authentic, the creators set out to cast dancers who could act, not actors who’d require dance doubles. The process spanned three months and many continents. It often felt—especially when casting two of the leads, roles that ultimately went to Kylie Jefferson and Barton Cowperthwaite—like “trying to find unicorns,” head choreographer and dance consultant Jennifer Nichols says. “To be at that level of dance skill is already a huge feat, and to be a brilliant actor on top of that is hard.”

Nichols was also tasked with making sure every other element of the production accurately reflected the ballet world. “The team consulted about how the shoe room would really look, how the studio was set up, how to tie a pointe shoe ribbon,” Nichols explains. “These are all dead giveaways unless they’re supervised by someone in the dance world. I was worried we wouldn’t have the time and money to make it all look right, but it was never pushed aside.”

Kylie Jefferson (left) and Daniela Norman in an episode of “Tiny Pretty Things” (Sophie Giraud courtesy Netflix)

Ballet-World Realness

“Tiny Pretty Things” explores issues many young ballet dancers grapple with: How do you befriend your biggest competition? How has racism stained the ballet world? How does a young dancer figure out their sexuality? How common are eating disorders among dancers? “In the past, entertainment often hasn’t done justice to the dance world,” Nichols says. “Not just the ups and downs of it, but also all the difficult work that goes into it.” Oren, played by Barton Cowperthwaite, struggles with his sexual identity and an eating disorder. June, played by Daniela Norman, is tortured by a mother who doesn’t believe in her talent. Bette, played by Casimere Jollette, lives in the shadow of her more gifted sister, a principal dancer in the company. Shane, played by Brennan Clost, worries that his male lover will leave him for a woman.

Kylie Jefferson, 25, who plays Neveah and earned her BFA at The Boston Conservatory, says her character’s storyline reflects her own experiences with racism in ballet from “top to bottom.” In the first episode, the head of the ballet school, played by Lauren Holly, glibly claims that Neveah, who is Black, was plucked out of Compton (she wasn’t); fellow dancers make fun of a YouTube clip of her dancing hip hop; and her ballet teacher critiques her every move (and clothing choice).

“At the Boston Conservatory, girls were complaining to the head of the dance division about parts I was getting,” she explains. “They said I was given them because I was Black. Don’t they think I was aware of the stares or forced smiles they gave me when I did more turns than they did, or my arabesques got higher?” She appreciates the show’s unvarnished portrayal of the challenges she and many other Black ballet dancers face. “Representation is so important,” she says. “I’m grateful to be part of a show that’s able to do that—and not just in one light.”

Using Dance to Tell the Story

The show’s conflicts play out in the dialogue, of course, but dance also plays a vital role in the storytelling. (A pas de deux between two dancers might preview an unexpected love story, for example.) That meant choosing choreographers was particularly important. “We asked ourselves: How can choreography amplify and reflect the inner workings of narrative and the psychology of the characters?” Nichols says. “How can the dance further the narrative without playing second fiddle to it?”

Five A-list choreographers were hired to reflect the show’s varied moods and styles: Guillaume Côté, Juliano Nunes, Garrett Smith, Tiler Peck, and Robert Binet. In typical entertainment-world fashion, they had relatively few rehearsals with the cast. Since time with each choreographer was so limited (dancers were often off shooting other scenes), Nichols—who was on set the whole season and choreographed all the in-class segments—acted as a go-between, helping the choreographers understand each dancer’s strengths.

Inside the Creative Process

The production process was fundamentally different from what the dancers, many of whom have impressive concert-world resumés, were accustomed to. “I learned that time is money!” Cowperthwaite says. “I’m used to performing onstage. The show goes how it goes, and you decompress and process after. When you’re shooting, it’s the same kind of pressure, but you have much less time to decompress. On set, you get your six to 10 takes, and you move on.”

The camaraderie and professionalism of the stellar cast helped facilitate the filming process. The dancer-actors soon became “best friends,” according to Cowperthwaite. “We would shoot all hours of the day and hang out all weekend. The dynamic was something to behold.”

The natural chemistry between Jefferson and Cowperthwaite, in particular, made their onscreen dancing feel seamless. “We started filming a scene where they’re paired for a Sleeping Beauty pas de deux, and immediately there was a spark between them,” Nichols says. “It’s written into the script, but it happened in real life, too. We all thought: ‘We’re really lucky to be able to pair them together.’ ”

The hope is that the show’s clear-eyed portrayal of ballet, and the way it showcases gifted dancers at the top of their game, will hook Netflix’s massive mainstream audience on dance. “When I got to set,” Jefferson says, “I knew that everything I’ve been through in my life—everyone who’s told me I wasn’t working hard enough, every heartbreak that had nothing to do with dance—all of that was to get me there. It was to get me there and to help me keep going.”

Meet Two “Tiny Pretty Things” Standouts

Age:

28

Higher education:

BFA in dance from the University of Arizona

Hometown studio:

Denver School of the Arts and The Academy of Colorado Ballet

Proudest career moments:

Performing the lead in Lar Lubovitch’s Men’s Stories, and going on as Jerry in An American in Paris on tour. “I got thrown on 15 minutes before curtain, when both the lead and alternate called out!” he says. “I’d never done it with lights or costumes or with the female lead. And it was April Fool’s. No one believed it!”

How he got the job on “Tiny Pretty Things”:

“I was in China with An American in Paris. I did a Skype audition from the basement of the theater during the one hour my Wi-Fi was functioning properly. It was a small miracle.”

What he’s been doing in quarantine:

“Working out, and taking ballet online three to four times a week. I’m also reading sci-fi and acting books, and working on my voice. I’ve been active on social media, supporting Black Lives Matter, learning to be an ally. I’m also involved with Vote Forward, a letter-writing campaign to engage underrepresented and unlikely voters.”

His advice to young dancers:

“Find your dance instincts, and then train in a style on the other end of the spectrum so you stay grounded and disciplined. My physicality pushes me towards contemporary, but I turn to ballet as my rock, my lightning rod.”

What the team says about him:

“He’s a brilliant dancer,” Jennifer Nichols, the show’s dance consultant, says. “He’s a sinewy chameleon. He can be powerful and snappy, or soft and fluid. He has a lot of training in a myriad of styles, and an extensive professional past. I remember within seconds thinking: ‘This kid can do anything.’ ”

Age:

25

Major:

BFA in contemporary dance performance, with an emphasis in pedagogy, from the Boston Conservatory

Hometown studio:

Debbie Allen Dance Academy. At 6, Jefferson was the youngest student to ever be admitted—the cutoff used to be 8. “From the beginning, Ms. Allen kept me close and pushed me beyond my limits,” Jefferson says.

Proudest career moment:

“Choreographing ScHoolboy Q’s ‘CHopstix’ music video. I was able to hire friends I grew up dancing with—African-American women performing ballet exceptionally on TV. It was the first time the community I grew up with and my craft were aligned. In that moment, it became clear that I would never give up.”

How she got the job on “Tiny Pretty Things”:

“I called so many dance studios in L.A. looking for space to make my audition tape, but they were all booked because so many dancers were auditioning for the show! The only time I could get was 7 pm on the night of the submission deadline. I spent the whole night editing. I was stressed-out getting it to upload!”

What she’s been doing in quarantine:

“Most mornings I wake up and mourn Breonna Taylor and turn on Lizzo and dance however I want to dance. If I want to put my leg up one second and twerk the next second, I will. I’m trying to set healthy patterns for myself, so I can get out and fight for my future and my future children. I’ve gotten to a point where I’m not asking for love or protection: I’m going to be that love and protection. I know that my spirit needs it, and I know my friends need it, too.”

Advice to young dancers:

“You have to show up for your lessons to receive your blessings. Stay 10 toes down in that. Sometimes you are the lesson you have to learn, and sometimes there are outward lessons. When you get shaky—questioning yourself, your confidence—the universe will respond to that.”

What the team says about her:

“There’s an innate grace and purity to Kylie’s lines,” Jennifer Nichols says. “There was an authenticity to her audition tape: This is Kylie dancing, not a graduate of such-and-such school, where you see their teacher speaking through them. There’s a real freedom to her movement. She comes alive when she dances.”