Nutcracker Secrets and Surprises: The Iconic Ballet’s Path From Critical Flop to Holiday Fixture

Literary Roots

E.T.A. Hoffmann, a German writer, penned the eerie and dark tale “Nutcracker and Mouse King” in 1816. About 30 years later, the French writer Alexandre Dumas took the Nutcracker story into his own hands, lightening things up and softening the character descriptions. Dumas even cheered up the name of the protagonist. “Marie Stahlbaum” (meaning “steel tree,” representing the repressive family Marie found herself in, which led her imagination to run wild) became “Clara Silberhaus” (translated to “silver house,” a magnificent home filled with shiny magic.)

![]() Snowflakes of the original cast, “The Nutcracker” at the Mariinsky Theatre, 1892. Photo by Walter E. Owen, Courtesy Dance Magazine Archives.

Snowflakes of the original cast, “The Nutcracker” at the Mariinsky Theatre, 1892. Photo by Walter E. Owen, Courtesy Dance Magazine Archives.

From Page to Stage

In 1892 St. Petersburg, choreographer Marius Petipa and composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky pulled the story off the page and onto the stage of the Mariinsky Theatre. But Petipa fell ill while choreographing The Nutcracker and handed his duties over to his assistant, Lev Ivanov. Critics at the 1892 premiere were not pleased. Balletomanes felt the work to be uneven, and lamented the lack of a main ballerina in the first act. Many thought that the story was too light compared to historically based stories.

Out of Russia

Despite its initial reception, the ballet survived, partially due to the success of Tchaikovsky’s score. Performances were scarce, though, as the Russian Revolution scattered its original dancers. The Nutcracker‘s first major exposure outside of Russia took place in London in 1934. Former Mariinsky ballet master Nikolas Sergeyev was tasked with staging Petipa’s story ballets on the Vic-Wells Ballet (today The Royal Ballet) from the original notation. The notes were incomplete and difficult to read, yet Sergeyev persisted, and The Nutcracker made it to the stage.

![]() Dancers from ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in “The Nutcracker” pas de deux. Photo Courtesy Dance Magazine Archives.

Dancers from ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in “The Nutcracker” pas de deux. Photo Courtesy Dance Magazine Archives.

An American Premiere

The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo brought an abridged version of The Nutcracker to the U.S. in 1940. Over the next decade, the company toured the ballet extensively, exposing it to audiences nationwide.

![]() Willam Christensen (center) with his brothers Lew and Harold. Photo Courtesy San Francisco Ballet.

Willam Christensen (center) with his brothers Lew and Harold. Photo Courtesy San Francisco Ballet.

Across the Country…

In 1944, San Francisco Ballet founding artistic director Willam Christensen choreographed the U.S.’s first full-length Nutcracker. Christensen later founded Ballet West, which continues to perform his version of The Nutcracker each year.

![]() Balanchine rehearsing the snow scene with NYCB. Photo by Frederick Melton, Courtesy Dance Magazine Archives.

Balanchine rehearsing the snow scene with NYCB. Photo by Frederick Melton, Courtesy Dance Magazine Archives.

A Christmas Staple

Though the ballet’s popularity was already growing, some historians suggest that George Balanchine was the first to irretrievably link the work to the holidays. As dance critic Robert Greskovic puts it, Balanchine was “responsible for making the ballet a fixture of the Christmas season and of a ballet company’s repertory.” New York City Ballet first presented Balanchine’s Nutcracker in February of 1954 but quickly recognized its holiday appeal and moved the ballet to December for the following year.

Nutcracker All Over

As regional ballet companies sprouted around the country, The Nutcracker became a staple.Today it’s a holiday tradition that keeps families coming back year after year; its mass appeal keeps ballet in mainstream culture. Many companies attract audiences by infusing the classic with their own regional heritage: Christopher Wheeldon’s Nutcracker for the Joffrey Ballet is set at Chicago’s 1893 world’s fair and The Washington Ballet serves a dose of American history with characters such as George Washington and King George III.

![]() George Washington in The Washington Ballet’s Nutcracker.” Photo by Carol Pratt, Courtesy The Washington Ballet.

George Washington in The Washington Ballet’s Nutcracker.” Photo by Carol Pratt, Courtesy The Washington Ballet.

The Nutcracker also serves as the financial backbone of companies nationwide. In 2016, San Francisco Ballet sold a total of 87,926 tickets to the holiday ballet and Boston Ballet sold a total of 92,907. Despite its humble roots, The Nutcracker is now the show that companies rely on to put on inventive and cutting-edge works throughout the rest of the year.

More fun facts…

- According to dance historian Doug Fullington, in the original 1892 scenario the Nutcracker has two sisters who graciously welcome Clara to the Land of Sweets with warm hugs.

![]() Pennsylvania Ballet’s Craig Wasserman in the Candy Cane variation. Photo by Alexander Iziliaev, Courtesy Pennsylvania Ballet.

Pennsylvania Ballet’s Craig Wasserman in the Candy Cane variation. Photo by Alexander Iziliaev, Courtesy Pennsylvania Ballet.

- The Candy Cane variation (danced to the Russian Trepak music) was choreographed by its original 1892 dancer, Alexandre Shiryaev. Dance critic Mindy Aloff says that Shiryaev was “possibly the first practitioner of hand-drawn animation; he notated his choreography in sequential drawings that could be projected to show the dance in movement.” Balanchine included Shiryaev’s original choreography in his Nutcracker.

- The ethereal twinkling sound in the Sugar Plum Fairy’s solo comes from the celesta, a rare instrument Tchaikovsky heard in France. “He had one sent to him essentially in secret,” says Fullington.

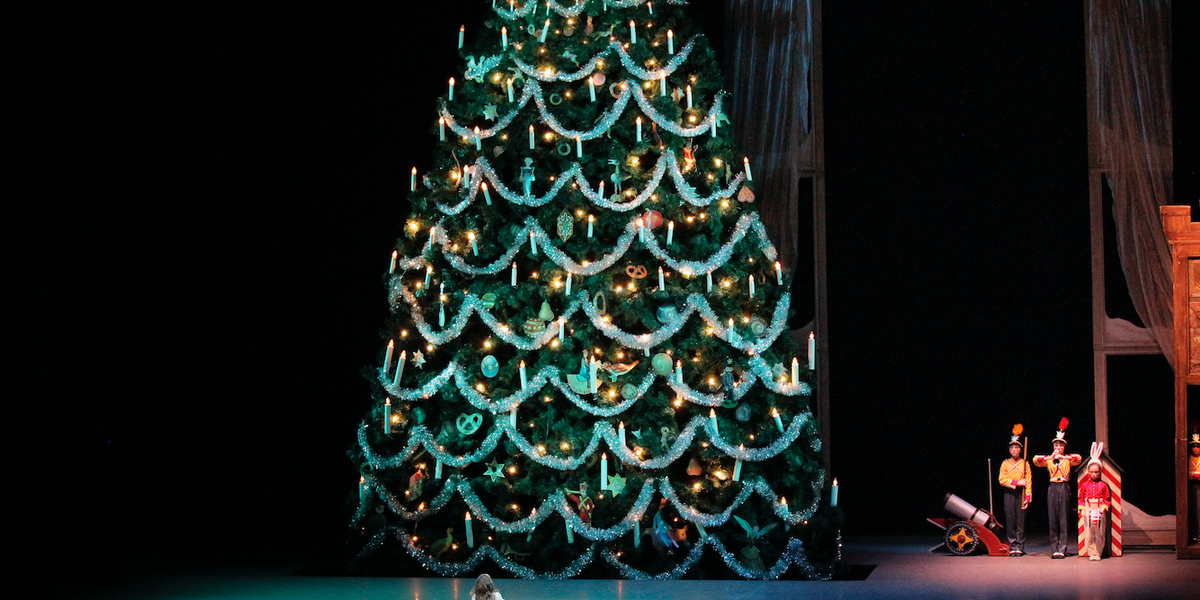

- Balanchine was given a budget of $40,000 for his 1954 premiere and, according to Aloff, he spent $25,000 on the Christmas tree alone. When asked if he could do without the tree Balanchine responded, “[The ballet] is the tree.” Today, New York City Ballet’s tree weighs one ton and can reach a full height of 41 feet.

![]() 1892 “Nutcracker” costume sketch by Ivan Vsevolozhsky of the Sugar Plum Fairy’s retinue. Courtesy Peter Koppers.

1892 “Nutcracker” costume sketch by Ivan Vsevolozhsky of the Sugar Plum Fairy’s retinue. Courtesy Peter Koppers.

- Choreographic notations suggest that the Cavalier’s variation was originally danced by a retinue of eight female fairies representing things like fruit, flowers and dreams. According to Fullington, Pavel Gerdt, the dancer who created the role, was likely too old to dance the variation himself.

- In Balanchine’s grand pas de deux, the lead ballerina holds an arabesque while gliding across the stage on pointe, pulled by her gallant prince. According to Fullington, Balanchine took this slide from Ivanov’s original choreography.

- The Sugar Plum Fairy’s prince’s original name was “Prince Coqueluche.” Meaning “whooping cough” in French, it likely referred to a lozenge candy.

![]() NYCB’s Unity Phelan and Silas Farley in Karinska’s Hot Chocolate costumes. Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy New York City Ballet.

NYCB’s Unity Phelan and Silas Farley in Karinska’s Hot Chocolate costumes. Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy New York City Ballet.

- NYCB costume designer Barbara Karinska included a small cameo on the bodice of the Hot Chocolate costumes. The soloists’ dresses bear the profile of NYCB co-founder Lincoln Kirstein, and the corps dancers’ feature the face of Balanchine himself.