Victor Caixeta Makes New Strides at Dutch National Ballet

On March 5, 2022, Victor Caixeta was supposed to dance Don Quixote on a stage that had come to feel like home: that of Russia’s Mariinsky Theatre, in St. Petersburg.

Instead, the 24-year-old from Brazil found himself in a minivan on the road to Tallinn, Estonia, with just one suitcase and his dog, Coco. Together with a group of other foreign dancers from the Mariinsky and the Bolshoi, he had decided to leave Russia in reaction to the country’s invasion of Ukraine a week earlier.

“If I had stayed, it meant that I was fine with what was going on, and I was not,” Caixeta says. “My morals always come first, before my ambitions.”

It was an abrupt pivot for a dancer on the brink of stardom in Russian ballet—the toughest possible environment for a classical dancer, yet one that came with an unmatched aura until the war. After five years of hard work and leading roles in ballets from Romeo and Juliet to La Bayadère, rewarded with a promotion to Mariinsky soloist in 2019, the shock of leaving reverberated through Caixeta’s body. “I got really, really sick. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t do anything,” he says.

The day before he left Russia, he had sent a Facebook message to Ted Brandsen, the director of Dutch National Ballet. A slightly older dancer from his school in Brazil, Daniel Robert Silva, had been with the company for six years, and Caixeta felt that Brandsen would be able to provide “guidance.” “Ted answered in five minutes and said: ‘Can I call you now?’ ” he remembers. Unbeknownst to him, Brandsen was already working on a fundraising campaign to create six extra positions for dancers displaced by the war. “I knew of him as a super-talented dancer, and I could imagine how he would suit the company,” Brandsen says. Within hours, Caixeta had a soloist contract—and a new, very different life waiting for him in Amsterdam.

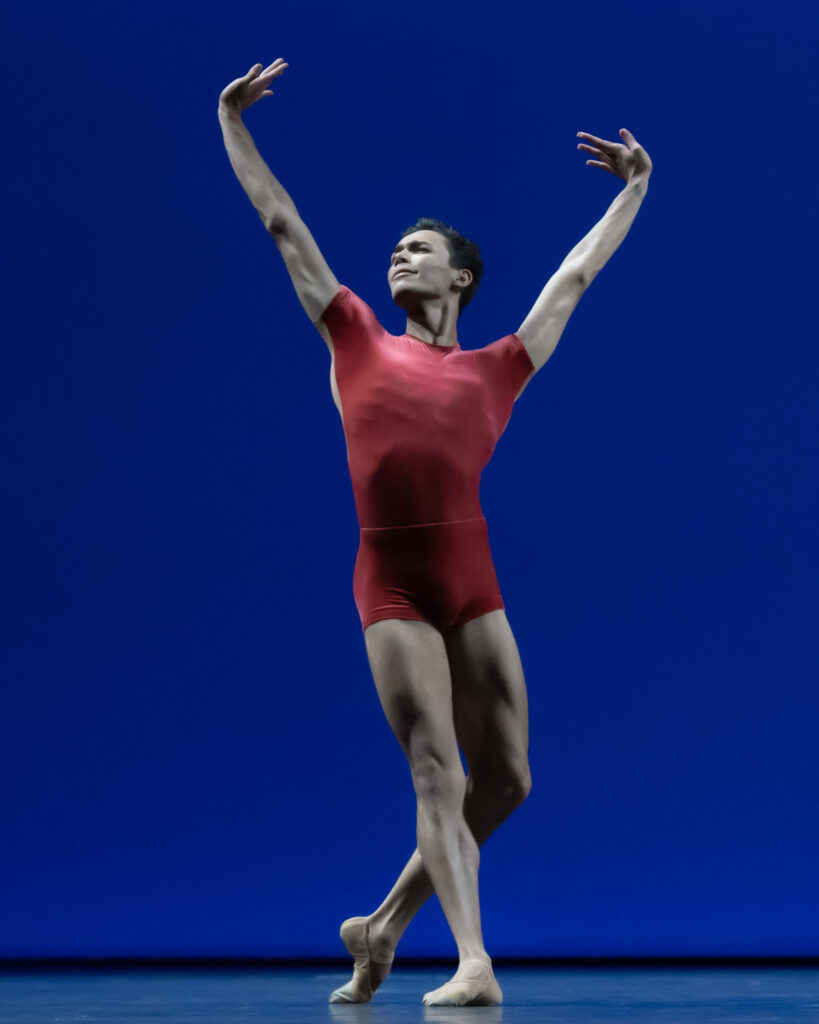

Over the past year and a half, he has taken to it with characteristic buoyancy, diving into works by Hans van Manen and William Forsythe, in addition to new versions of classics like Raymonda. Last June, on DNB’s home stage, he found joy in the technical clarity The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude requires, his long limbs playfully expanding Forsythe’s fast-moving geometric shapes into space.

“It was a very, very rapid adjustment,” says Brandsen, who promoted him to principal this past spring. “Everybody who has a chance to work with him just enjoys that experience because he’s very open and keen to learn.” Former Bolshoi star Olga Smirnova, who also left Russia in protest and joined Dutch National Ballet, describes Caixeta—now a frequent partner—as “radiant and energetic onstage, and easygoing and open offstage.” “He is a true and generous friend, who brightens up any company,” she adds.

Late Start, Early Commitment

Caixeta was a quick study from his first brush with dance. When Mariinsky Ballet director Yuri Fateev took him aside to offer him a job, midway through the first round of the Moscow International Ballet Competition in 2017, he had had just five years’ training under his belt—all thanks to Guiomar Boaventura, the director of a social project in his home city of Uberlândia, in southeastern Brazil. Boaventura, who offers Vaganova-style dance training to children from underprivileged backgrounds, spotted the 12-year-old Caixeta at school and immediately offered to take him on.

There was one condition: that he take ballet seriously. “Not just as an extracurricular, but to become a dancer,” Caixeta says, even though his preteen self had no idea what that entailed. The days were long, but he relished the challenge. “I was the best at everything then, also in school, and ballet was finally something that I wasn’t the best at.”

Boaventura also devised a plan for Caixeta to get ahead through competitions. “She told me: ‘You have no money for summer schools or auditions, so that’s going to be your way.’ ” A year or so into his training, he was a finalist at Youth America Grand Prix; the Prix de Lausanne followed at 15. While Caixeta didn’t reach the finals there, he received 18 scholarship offers from partner schools. After an unhappy stint at Canada’s National Ballet School, where he was bored with the slower pace, his Brazilian teacher arranged for him to get a fresh start at Berlin’s Staatliche Ballettschule.

There, Caixeta kept entering competitions, where his precocious mix of elegance and ebullience was an instant draw. When Fateev invited him to join the Mariinsky at the Moscow IBC, having only seen him in one Nutcracker variation, Caixeta thought “it was a scam,” he says with a laugh. “I didn’t even know there were foreigners at the Mariinsky.”

Living a Dream

Yet weeks later, he was in St. Petersburg. “I think I lived in a dream for three months until I realized I was actually there,” Caixeta says. He wasn’t lonely: A small group of foreigners all joined the Mariinsky Ballet the same year, including Japanese dancer May Nagahisa, who became his frequent partner.

In a company where personal coaches are “like parents,” as Caixeta puts it, he also soon had a mentor to look after him: Gennady Selyutsky, then 79, a Mariinsky veteran whose former pupils included Farukh Ruzimatov and Leonid Sarafanov. “He had just been really sick, and when we started working together, he suddenly got so much energy,” Caixeta says. “Once, we worked for three months without a single day off.”

Their bond was such that in the evenings, Selyutsky called to check on him and offer additional corrections. “Even when I was injured for six months, I still had rehearsals. He would put me in front of the mirror to work on my arms and facial expressions. He knew, in a way, that he needed to give me everything he knew before he went.” (Selyutsky died in 2020.)

Caixeta soon made his mark in leading roles. Romeo and Juliet with Nagahisa was a high point—“We had maybe 10 or 15 curtain calls. I still have shivers thinking about it,” he says—and by the end, he was dancing Don Quixote nearly every monthunder the guidance of a new coach, Viktor Baranov.

When Russia suddenly invaded Ukraine, in late February 2022, Caixeta happened to be guesting in the Russian city of Vladivostok with Yekaterina Chebykina, a Ukrainian colleague. “She started to get calls from her family leaving Kyiv, going to a bomb shelter,” Caixeta says.

Upon his return to St. Petersburg, he and other foreign dancers at the Mariinsky demanded a meeting with Fateev. “He was very emotional. He had brought us all there and he didn’t want to lose us.”

Making Adjustments

At Dutch National Ballet, Caixeta was relieved to find someone who had gone through similar upheaval in Smirnova. “She has been like an anchor for me,” he says. There were ups and downs early on: A year ago, he was sidelined by a back injury most likely caused by the transition from the Mariinsky’s raked floor to a flat one in Amsterdam. “Coming back to a normal floor, I had a lot of pain,” he says.

Still, while at the Mariinsky dancers had to cover a lot of their medical and physiotherapy expenses, Caixeta found ready help from Dutch National Ballet’s in-house health team: “Arriving here, it was luxury.” He has also embraced the company’s more human schedule. “Weekends, I’d never heard of,” he says with a warm chuckle. “Here we rehearse more than we perform. I go onstage and feel prepared, I’m much more calm.”

Working regularly with choreographers has been another perk. His rehearsals with Forsythe last season brought “inspiration for a lifetime,” Caixeta says. “He brought things out of my dance that I didn’t even know I had.”

And life in the Netherlands, as well as his frequent travels around Europe for guest stints and for pleasure, has been an eye-opener beyond ballet. “People had such strong opinions about everything in Russia. You had to be a certain way, and I’ve always been open-minded. My mom raised us to be free,” Caixeta says. “I’m so grateful for the place I am now—for the freedom to be myself. I’m taking care of Victor the person, not just the dancer.”