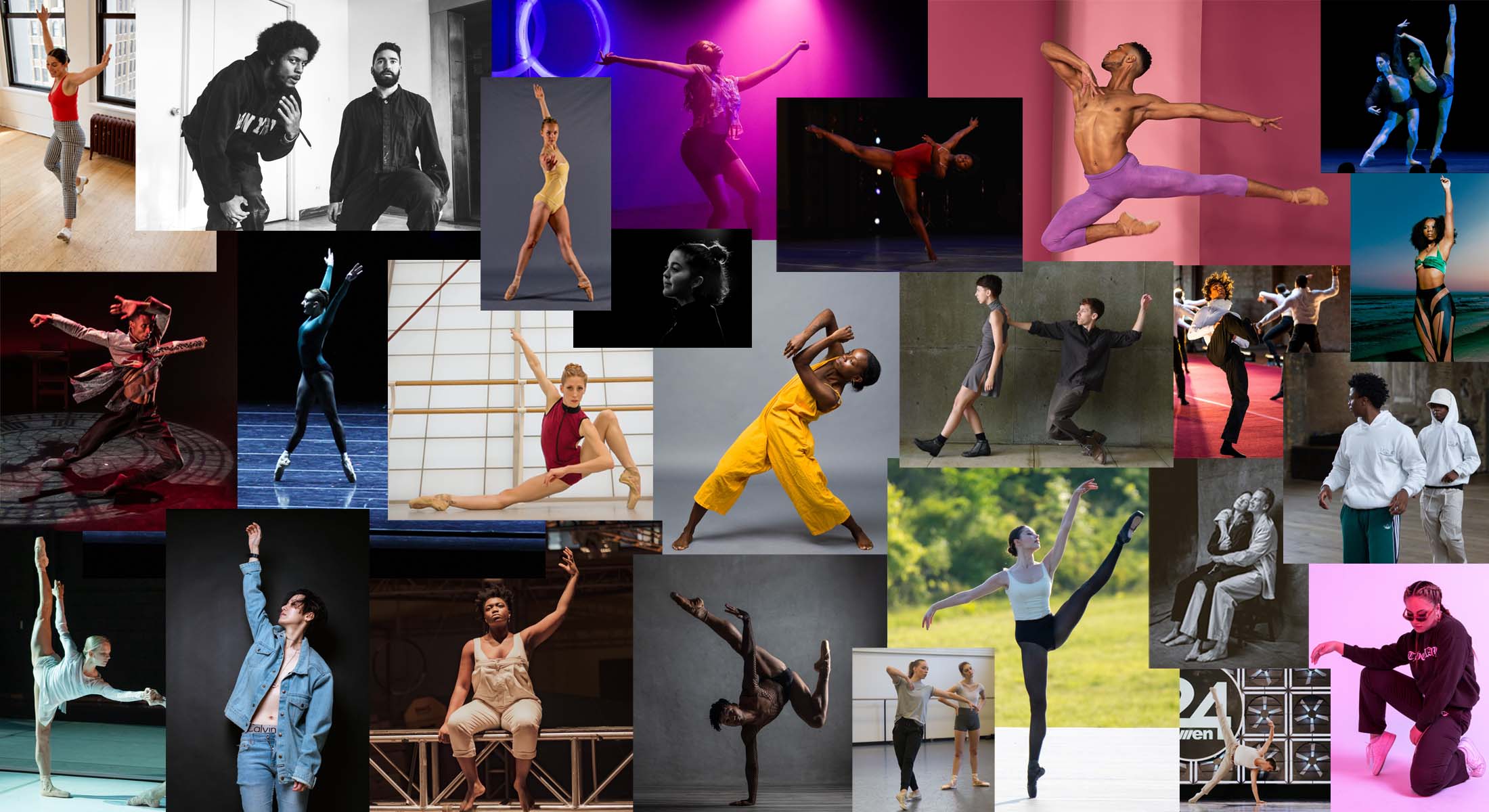

Meet the Ballet Dancers, Choreographers and Companies from Dance Magazine’s 2022 “25 to Watch”

Our friends at Dance Magazine announced their annual “25 to Watch” list earlier this week. The round-up features emerging dancers, choreographers and companies you should know, spanning multiple dance genres. And, of course, we can’t help but feel excited about those from the ballet world. Read on to learn more about them, then be sure to read the full “25 to Watch” list here.

Adriana Pierce

Adriana Pierce’s career thus far looks like a jack-of-all-trades, master-of-many laundry list of dream gigs: dancing in Miami City Ballet, the 2018 Broadway revival of Carousel, FX’s “Fosse/Verdon” and the new West Side Story movie, plus choreographic opportunities that continue to grow in scale. Though she came out while a student at the School of American Ballet, it wasn’t until she gathered a group of fellow queer women and nonbinary dancers over Zoom in 2020 that “I really felt a sense of community about my identity and sexuality through ballet,” she says. Pierce doesn’t want the next generation of queer dancers to have to compartmentalize their identities as she did. Enter #QueerTheBallet, an ambitious producing and education initiative she launched last year to get more queer stories onstage.

Pierce’s own choreography interrogates what equitable partnering looks like and how pointe work might be divorced from its gendered history, research she put into practice in 2021 with a piece for American Ballet Theatre dancers and a virtual commission for The Joyce Theater, both duets for two women. Next up is a Carolina Ballet commission in the spring. Odds are, Pierce will continue pushing ballet forward in ever more eclectic ways—her bucket list items include creating immersive ballet work, directing and choreographing on Broadway, and creating a full-length queer narrative ballet: “I want people to feel as used to seeing queer stories on a ballet stage as they are used to seeing Giselle.” —Lauren Wingenroth

Ballet22

There was something special about the Odalisque pas de trois that Ballet22 performed in its summer 2021 digital season. It wasn’t the crisp pointe work, the crystalline turns or the vibrant musicality, all of which were abundant. It was that the Ballet22 dancers in the traditionally all-female variation from Le Corsaire were male—and not men in drag hamming it up for laughs, but, quite simply, male dancers expressing their artistry on pointe.

Founded as a pandemic project by artistic director Roberto Vega Ortiz and executive director Theresa Knudson, Ballet22 invites male, mxn, transgender and nonbinary dancers to train and perform on pointe in their authentic gender identity. The company grew out of Zoom classes offered by Vega Ortiz and his close friend Carlos Hopuy of Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo in early 2020, and gained an international following so quickly that Vega Ortiz and Knudson were able to launch the performing company in December 2020. Ballet22 has drawn dancers like New York City Ballet’s Gilbert Bolden III, Boston Ballet’s Daniel R. Durrett, San Francisco Ballet soloist Diego Cruz, and the Trocks’ Duane Gosa, and commissions by choreographers like Myles Thatcher, Ramón Oller and Ben Needham-Wood. As the greater cultural conversation around gender goes on, Ballet22 is overturning ballet’s rules about who gets to dance, what they get to dance and how they get to dance. —Claudia Bauer

Courtney Nitting

Courtney Nitting attacks choreography with catlike quickness. In Kansas City Ballet artistic director Devon Carney’s 2021 work Sandhur, her rapid-paced turns and leaps electrified. “I love speed,” she says. “Petit allégro is my favorite, and I feel it can never be fast enough.”

The 24-year-old speed demon was born in Lafayette, New Jersey, and began her training at New Jersey School of Ballet. She then attended School of American Ballet before joining Pennsylvania Ballet II in 2017 and Kansas City Ballet a year later. “Courtney is a force to be reckoned with,” says Carney. “She has a diverse dynamic range with spectacularly fast footwork. Every time she enters the stage, she lights it up with intensity and joie de vivre.”

Having already danced featured roles in Sandhur and in William Forsythe’s In the middle, somewhat elevated, Nitting’s career, which has also included choreographing for Kansas City Ballet, is beginning to switch into high gear. —Steve Sucato

Maxfield Haynes

Illuminating possibility comes naturally to Maxfield Haynes. The nonbinary phenom has carved out a brilliant career for themself, demolishing machismo stereotypes while blitzing across the stage in pointe shoes or heels, and playfully partnering their fellow dancers with aplomb.

Haynes learned to embrace their multifaceted identity early on and came to reject the binary gender presentations they encountered during their classical ballet training. This “do-everything” spirit helped them juggle apprenticing with Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo while studying at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. It continued to serve them well as they performed soloist roles with Complexions Contemporary Ballet—both on pointe and off—dispatched crisp batterie as the bird in Isaac Mizrahi’s Peter & the Wolf, and, this fall, made a triumphant return to the Trocks. But the Kentucky native had a true awakening this past summer as part of Ballez’s Giselle of Loneliness. Their solo blended bursts of traditionally feminine sweetness with soaring leaps, all while illustrating that dance is love—regardless of one’s race or gender presentation. —Juan Michael Porter II

Adriana Wagenveld

Grace, grit, athleticism and versatility are what garnered Adriana Wagenveld soloist roles in Trey McIntyre’s Wild Sweet Love and Alejandro Cerrudo’s Extremely Close in her first season as a full company member at Grand Rapids Ballet. They are also what have the 22-year-old on the cusp of company stardom.

Originally from Puerto Rico, Wagenveld began her dance training in Crete, Illinois. After attending Grand Rapids Ballet’s 2015 summer intensive on scholarship, she was asked to join the company as a trainee. She became a main company member in 2019. “There is a lot of emotion behind her eyes, and she takes on roles with verve and determination,” says artistic director James Sofranko.

Wagenveld has hypermobility in her joints from Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which leads to exaggerated lines that she says are both a blessing and a curse. Countering that hypermobility with strength, she says, has made her project “more of a powerhouse-dancer vibe than a princess one.” —Steve Sucato

Arielle Smith

Whoops of joy greeted Arielle Smith’s Jolly Folly when it closed English National Ballet’s return to live performance in London last spring. The ballet bounced giddily along to classical pops remixed by a Cuban big-band, its tilting, tumbling ensemble dressed in black tie and tails. It was an absolute blast, delivering a genuine jolt of delight.

The Havana-born Smith, 25, previously honed a storyteller’s instinct under the mentorship of Matthew Bourne, who made her associate choreographer on his 2019 Romeo + Juliet. Smith’s early work has emerged with life-enhancing wit and assurance. Her voice is already distinctive—who knows how it will develop and where it will take her? She’s more than just a fistful of fun. —David Jays

PARA.MAR Dance Theatre

PARA.MAR Dance Theatre bolted out of the gate fully ready to steamroll the status quo. Stephanie Martinez’s new contemporary ballet company debuted with performances of her fierce kiss. atop a red carpet in a Chicago parking lot in October 2020. With a cast of fearless dancers, the piece captured the restless angst of isolation and the languishing sensuality of pure explosive action, along with a hard to define quirky charm.

Martinez, who has created works for The Joffrey Ballet, Ballet Hispánico and Nashville Ballet, among others, formed her troupe in the midst of a pandemic when dancers desperately needed to work and the field desperately needed to diversify. With the motto “together, with, and for,” Martinez’s mission includes elevating BIPOC voices in contemporary ballet. PARA.MAR premiered works by Jennifer Archibald and Lucas Crandall in Chicago last spring and performed them at the inaugural Carmel Dance Festival last summer; next up are commissions by Robyn Mineko Williams and Keerati Jinakunwiphat, among others, along with a new work by Martinez. —Nancy Wozny

Sierra Armstrong

Back in her ABT Studio Company days, Sierra Armstrong’s luxuriant lines and keen emotional intelligence piqued the interest of ballet fans. But after joining American Ballet Theatre’s main company in 2017, Armstrong had few chances to develop those gifts, tasked with a slate of ensemble parts that kept her both busy and in the background.

When the pandemic shut down the ABT machine, Armstrong found space for self-discovery. “I was in the studio a lot by myself, dancing by myself, doing all these things by myself,” says Armstrong, now 22. “It was a lonely time, but a time where I really came into my own, too.”

Featured roles in a series of small-scale, COVID-friendly projects showcased that growth. Last February, she brought a new depth of artistry to Adriana Pierce’s Overlook, a tender pas de deux with fellow female ABT corps member Remy Young. Armstrong became a particular muse to ABT star and choreographer James Whiteside, originating a lead in his bubble-residency premiere City of Women, and taking on a principal part in his New American Romance during an outdoor performance at Rockefeller Center. Here’s hoping those opportunities will lead to more, at ABT and beyond it, as the world reopens. —Margaret Fuhrer

Johnathon Hart

“Naturally gifted” best describes Johnathon Hart. After being accepted to the Chicago High School for the Arts at age 15 with no formal dance training, he attended San Francisco Ballet School’s summer intensive on full scholarship, followed by two years full time at the school before joining BalletMet in 2020. “He is a huge talent,” says BalletMet artistic director Edwaard Liang of the 21-year-old.

In Karen Wing’s 2021 Verbena, Hart coupled his enviable facility and squeaky-clean technique with a bold stage presence. He soared in leaps that devoured the space and swirled his body in artistic brushstrokes to riveting effect. While most at home in contemporary works, the versatile Hart says he is looking forward to dancing more classical roles in 2022. —Steve Sucato

Darian Kane

Darian Kane hadn’t planned to choreograph. But when the pandemic hit, and Atlanta Ballet artistic director Gennadi Nedvigin called for company members to create works on fellow dancers, Kane stepped up and choreographed her first piece, Dr. Rainbow’s Infinity Mirror. She discovered what she lightly dubs an “indie-pop contemporary” style that’s worlds away from her regal classical ballet persona.

To nostalgic piano and eerie melodies reminiscent of early sci-fi movies, dancer Sujin Han appears in black tuxedo tails and rainbow toe socks—think Charlie Chaplin meets The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. With elastic développés, Han takes exaggerated strides forward and steps through an invisible frame. She whirls, leaps and moonwalks, her arms striking lines through the space around her as if painting a more vivid realm. Though light on the surface, Dr. Rainbow expresses a full range of human experience—especially struggles with mental health.

Dr. Rainbow was so well received last spring that Atlanta Ballet is producing an expanded version, set for a February premiere. And Kane, now 25, has fallen in love with choreographing: “It’s the first time I’ve had a voice in my own industry.” —Cynthia Bond Perry

Mthuthuzeli November

Mthuthuzeli November is pushing the boundaries of whose stories are given a voice in ballet. Born and raised in Cape Town, he moved to the UK to join Ballet Black in 2015, creating his first piece for the company in 2016. The same year, he established M22 Movement Lab, his own choreographic platform, and devised Point of Collapse, an emotive solo performed by Precious Adams for English National Ballet’s Emerging Dancer Competition. It wasn’t until 2019, however, with the Olivier and Black British Theatre Award–winning work Ingoma, that November really started to attract international attention.

Inspired by the paintings of South Africa’s Gerard Sekoto, Ingoma imagines the struggles of Black miners and their families in 1946, when 60,000 of them went on strike. Wearing a mix of wellies and pointe shoes, the dancers create percussive rhythms that drive the piece forward, their powerful motions poetically juxtaposed with moments of pleading, anxiety and vulnerability. Fusing ballet with African dance and singing, the work saw November develop a distinctive, gesture-filled movement language that is entirely his own.

November has since been in increasing demand, even during the darkest days of the pandemic: He created an online version of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater for Cape Town Opera and a dance film for Northern Ballet. Ballet Black also returned to live performance in October with the premiere of his work The Waiting Game. With November’s unwavering motivation, abundant talent and timely topics, audiences shouldn’t have to wait long to see more from him. —Emily May

Genevieve Penn Nabity

National Ballet of Canada artistic staff, choreographers and fellow dancers alike heap praise on 21-year-old second soloist Genevieve Penn Nabity. “The joy she finds in movement is translated through every fiber of her being,” says choreographic associate Robert Binet, who has been casting her in his works ever since her days at Canada’s National Ballet School. Her full-bodied performance style and versatility have also been showcased in Skylar Campbell’s eponymous collective. He adds, “Her quality of movement, and ability to mold into any style thrown her way, is a constant source of inspiration.”

Penn Nabity joined NBoC as an apprentice in 2018, and was promoted to the corps de ballet and received the RBC Emerging Artist Award in 2019. Associate artistic director Christopher Stowell fast-tracked her career after seeing how she took possession of even minor roles in ballets like The Dream and The Nutcracker. “Genevieve connects movement with articulation and finesse while bringing a seamless ease to even the most challenging technical hurdles,” he says.

Penn Nabity has since danced in The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle, Études and, just before the lockdowns, Crystal Pite’s Angels’ Atlas. During the pandemic, she performed in the digital premiere of Binet’s The Dreamers Ever Leave You, reprising her role outdoors for a live audience last summer shortly after her promotion to second soloist. Next up is a new ballet by principal dancer Siphesihle November, set to debut in March. “I feel the stars have aligned,” Penn Nabity says. “Nothing is holding me back.” —Deirdre Kelly

Header photo credits, left to right, top to bottom: Raina Brie, Courtesy Carminucci; Umi Akiyoshi, Courtesy Baye & Asa; Ray Nard Imagemaker, Courtesy Grand Rapids Ballet; Courtesy Mims; Kaylee Wong, Courtesy Green; Jennifer Zmuda, Courtesy BalletMet; Alexander Irwin, Courtesy Ballet22; Christina Massad, Courtesy Terminus Modern Ballet Theatre; Elizabeth Snell, Courtesy Kansas City Ballet; Brian Wallenberg, Courtesy Atlanta Ballet; Tom Clark, Courtesy English National Ballet; Frank Ishman, Courtesy Hubbard Street Dance Chicago; Sue Murad, Courtesy Vidrin; Todd Rosenberg, Courtesy PARA.MAR Dance Theatre; Banvoa, Courtesy Jackson; Skye Weiss, Courtesy November; Karolina Kuras, Courtesy National Ballet of Canada; Rose Lu, Courtesy Park; Chidozie Ekwensi, Courtesy Ude; Steven Vandervelden, Courtesy Haynes; Rosalie O’Connor, Courtesy Pierce; Alex DiMattia, Courtesy ABT; Rahi Rezvani, Courtesy the van Opstals; 24 Seven Dance Convention, Courtesy Williams; Joe Toreno