Carolina Ballet’s Orpheus & Eurydice: Mythical Mystery, Love, and Art

In the summer of 2017, Carolina Ballet founding artistic director Robert Weiss and renowned composer J. Mark Scearce huddled together at the back of an Italian restaurant in Raleigh, North Carolina. Riding the high of their successful 2016 world premiere ballet Macbeth, the two friends and frequent collaborators grabbed a napkin and penned the blueprints for their next project: a new full-length of the classic myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. This month, the ballet, Orpheus & Eurydice, finally makes its premiere at the Raleigh Memorial Auditorium April 27 to 30, with live accompaniment by the Chamber Orchestra of the Triangle.

A few obstacles delayed Orpheus & Eurydice’s debut. “First, the company didn’t have the money, then the pandemic happened,” says Weiss. “We had the libretto and music finished for years before we began working on it in the studio last summer.” But now, with the hour-and-40-minutes’ worth of choreography complete, and original costumes and sets designed by celebrated artist Susan Tammany, the curtain is set to rise on Raleigh’s own ancient Greece.

In Carolina Ballet’s version of the myth, which draws especially from the Roman poet Ovid’s telling, the god Apollo teaches Orpheus how to harness power through music by playing the lyre. This power comes in handy when Orpheus must embark on an epic journey through Hell to retrieve his love, Eurydice, who has died of a snakebite. Hades, god of the underworld, allows Orpheus to take Eurydice back to the realm of the living so long as he does not look at her the entire way. Just as Orpheus crosses the threshold, he turns back a moment too soon and tragically loses Eurydice again—this time forever. After several years of roaming the earth in grief, Orpheus is killed and finally reunites with Eurydice in the afterlife.

“It’s the greatest love story ever told,” says Scearce, who had dreamed of composing his own Orpheus for years. Having written eight ballets with Weiss (and 12 for the company total), he felt the two of them were ready to tackle the beloved myth, which has recently gained traction in pop culture with the Broadway musical Hadesdown. “I’ve been working [with Weiss] for 25 years,” says Scearce. “He’s as much a dramaturge as a choreographer.”

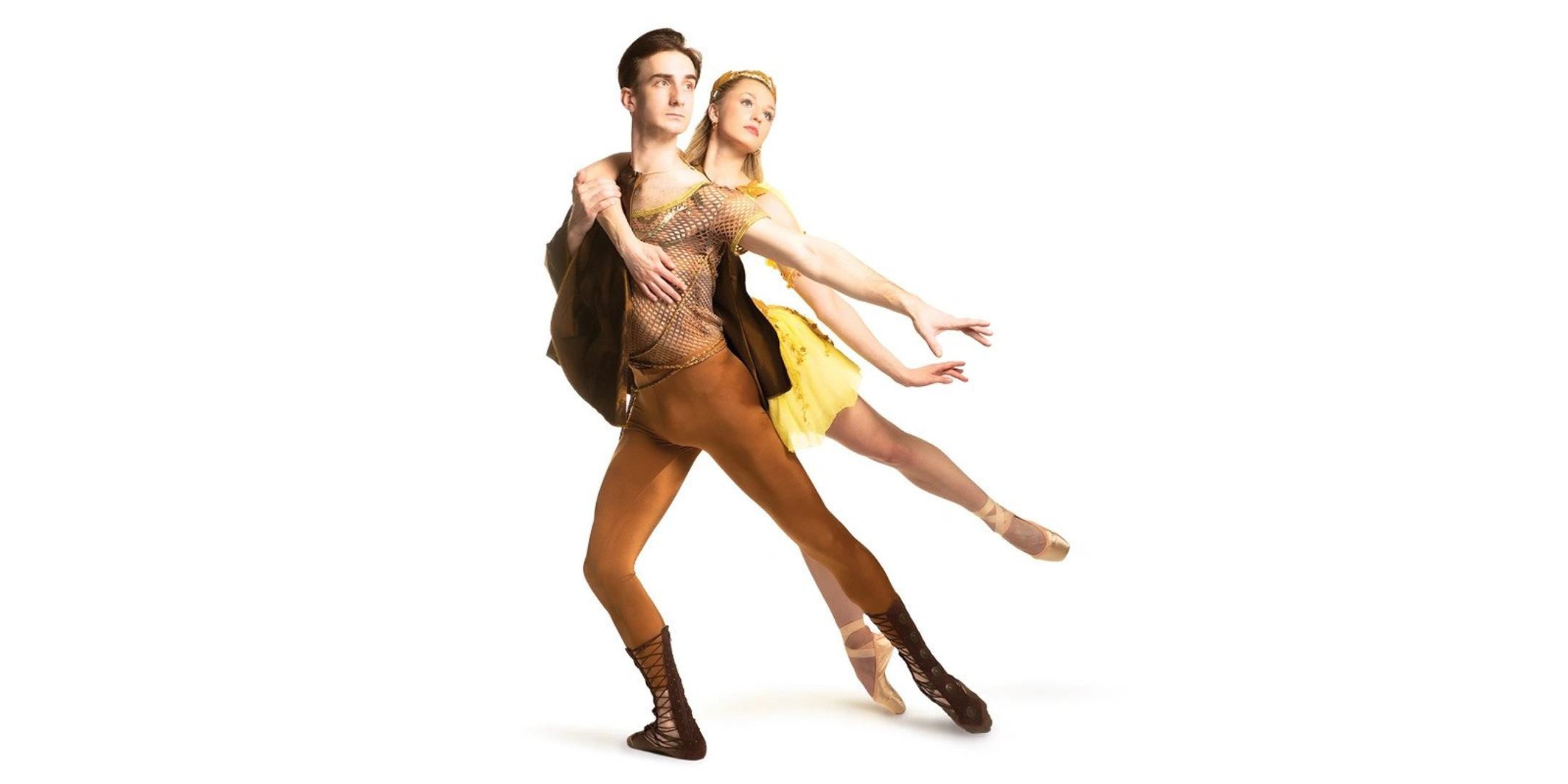

The ballet involves a slew of unique principal and soloist roles—including the titular ill-fated lovers, Hades, Persephone, Apollo, the three Furies, an enchanting nightingale, and even Cerberus, a mythic three-headed dog rendered by three dancers in a cape. But the libretto, as Carolina Ballet principal Kiefer Curtis explains, is simple despite its emotional richness. “It’s not the longest, most intricate story, so imagery works well,” he says. The role of Orpheus was created on Curtis, who has looked to multiple sources to inform his characterization—which, he notes, is appropriate given the myth’s many iterations throughout history. He has also appreciated Weiss and Scearce bringing photos, books, and quotes to rehearsals to provide additional sources of inspiration. “We’re trying to pull from all of them,” says Curtis.

Weiss looked at one in particular to inform his choreography for the legendary ascent from Hell: an 1893 sculpture by Auguste Rodin. Rather than integrating a blindfold or mask as George Balanchine did in his Orpheus, Weiss decided to choreograph the lovers’ entire ascension pas de deux referencing Rodin’s sculpture, with Orpheus covering his eyes with his hands and arms. “I knew it would be a choreographic challenge,” he says, “but I felt it would enhance the imagery.”

Curtis agrees: “I hardly see my partner [Madeline Rogers] in that pas—it’s been a challenge telling if she’s even on her leg! But sometimes I’ll get so into it and realize I’ve actually had my eyes closed, or my hand’s completely covering them when I should be peeking through my fingers.” The effect, he explains, pays off with the mystique and tension it creates. “The audience doesn’t know what’s coming next.”

Tammany’s scenic design, a series of watercolor paintings projected below the proscenium and onto the back wall of the stage, adds to the air of mystery by creating an otherworldly mood—as does Scearce’s composition, which is filled with complex chords and arpeggios that create a sense of paced, yet driving, anticipation. But despite the ballet’s mystique and mythic elements, its universality and emotional pull are what really make the magic, says Scearce. “We’ve all lost someone. If I do my job right—if we all do our jobs right—while watching, you’ll find that you’ll commune with the ones you’ve lost.”