Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s Coco Chanel Brings an Antiheroine to Atlanta Ballet

Choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa finds fertile ground for storytelling in the lives of great women.

“It’s interesting as a choreographer to expose the context a woman comes from, how she had to behave and survive,” says Ochoa. “I find it more interesting than fairies and princesses.”

To date, her canon of new story ballets includes four powerful, and in some cases morally questionable, women: Eva Perón, Frida Kahlo, Maria Callas, and Coco Chanel. After a world premiere with Hong Kong Ballet last year, Ochoa’s Coco Chanel, which tells the renowned fashion designer’s story, makes its U.S. premiere on February 9 with Atlanta Ballet at Cobb Energy Centre before moving on to Queensland Ballet next October. Two years in the making, and postponed twice by COVID, the ballet explores Chanel’s complex life and fits with Ochoa’s demands for drama.

“For me, the hero is actually a bit of an antihero. She’s not the nicest person,” says Ochoa of Chanel. “And for ballerinas who are always used to being this frail, very elegant, soft-spoken character, I have to tell them, no, she knows what she wants. Or she thinks: Maybe I can use him. I share all that thought process with the dancers.”

For AB company dancer Mikaela Santos, who is cast as Chanel, portraying such a commanding and complicated persona has been different from any role she has encountered before. Ochoa’s process has entailed extensive research, a detailed approach to acting, and a vast arsenal of movement qualities. But Santos notes: “I have the freedom to be a human being.”

The two-act ballet, developed with dramaturge Nancy Meckler and a commissioned score from Peter Salem, tracks Chanel’s life as a rags-to-riches myth. It begins with Chanel at age 18, when she began working as a seamstress, and follows the building of her fashion empire (and nearly losing it) up until her comeback collection in 1953. Working through Chanel’s very eventful life required much editing.

“I had to make choices about what I find theatrically interesting,” says Ochoa. “It’s not a documentary. I can’t put all the elements in the piece, but, yes, there’s a lot to see.”

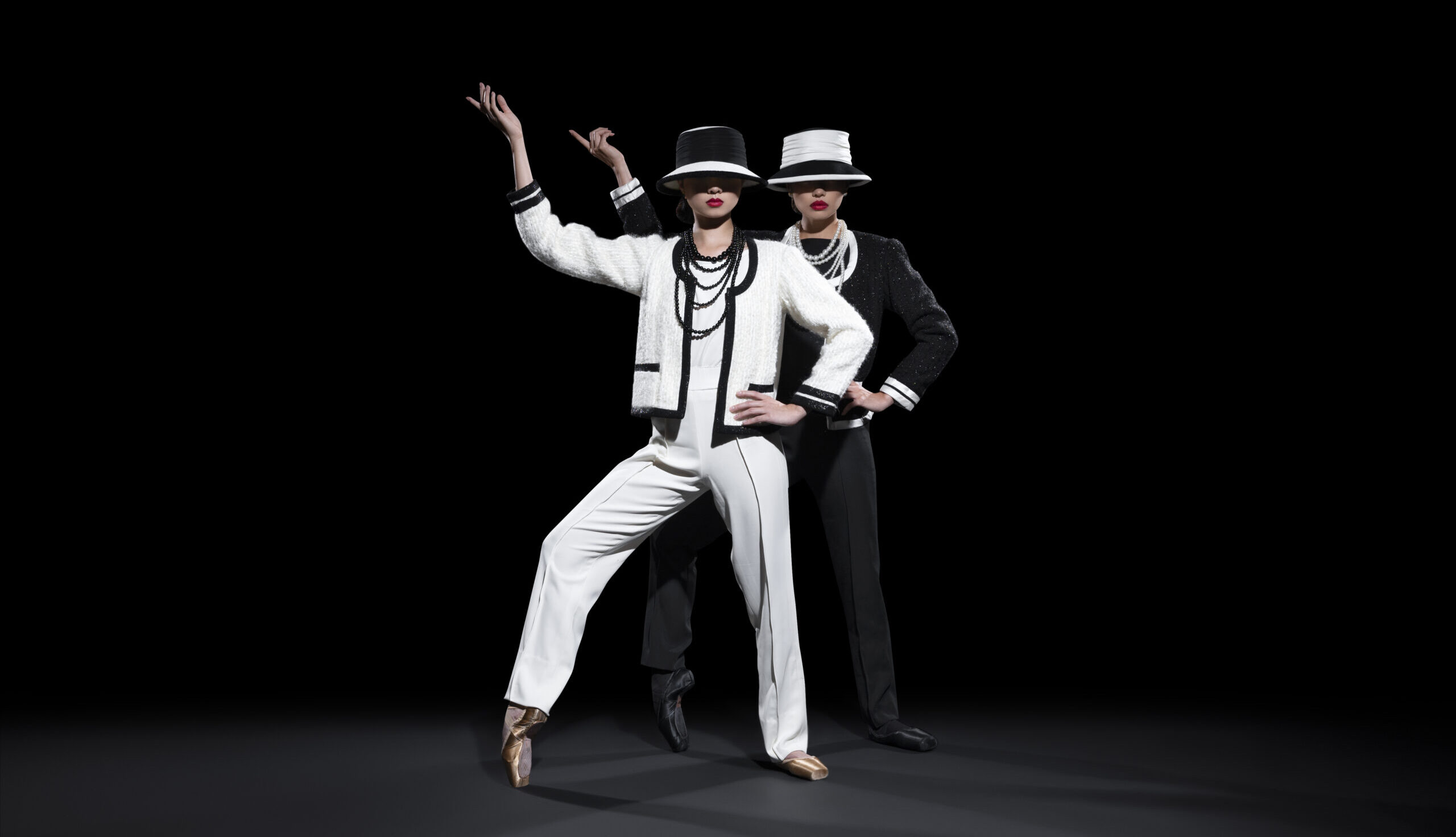

The elegance of Chanel’s style is channeled through Jérôme Kaplan’s minimalist set and costumes that evoke, rather than explicitly re-create, her designs. The movement style morphs to fit each episode in Chanel’s life journey and reflects Ochoa’s fascination with how the intricacies of body language can evoke a person’s nature.

The storyline follows several of Chanel’s complicated love affairs and her business partnership with Pierre Wertheimer, the French Jewish businessman who financed the Chanel brand and funded Chanel’s comeback after the war. This choice required Ochoa to pivot from the more typical dramatic tension of a love triangle, creating more roles for the men and partners for Santos.

“Coco Chanel was a businesswoman in a man’s world, and she had to deal with sexism,” says Ochoa. “She had to use her womanhood as a weapon, and entice men to give her the money, to trust her. And at the same time she was constantly fighting for her independence. So she was a smart cookie and very opportunistic in that aspect.”

Of Chanel’s famous relationships, Ochoa includes an episode with Igor Stravinsky, who was married with children, and, more controversially, Baron Hans Gunther von Dincklage, who was special attaché to the German Embassy in Paris and known to be a Gestapo spy during World War II. The Stravinsky scene acknowledges how Chanel remained Stravinsky’s patron even after the short affair and nests within it a mini ballet, nodding to both the music of Le Sacre du Printemps and Nijinsky’s work.

Ochoa’s desire to bring awareness to Chanel’s relationship with Dincklage—and now well-documented antisemitism and Nazi collaboration—came from her own surprise at discovering this in her research.

“It was something that I didn’t know when I said I wanted to do the ballet. And I was really amazed that I didn’t know,” explains Ochoa. “I’m sure a lot of people don’t know when they buy a Chanel bag that there were darker chapters in her life. I thought it was good to expose them, so that people are aware.”

To provide greater historical insight into this part of Chanel’s past in Vichy, France, and to encourage more education and conversation around antisemitism, Atlanta Ballet is partnering with the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum. Their partnered community engagement programming includes a panel discussion called “The Complicated Legacy of Coco Chanel,” with Atlanta Ballet’s artistic director Gennadi Nedvigin, Ochoa, and Rabbi Joseph Prass. The conversation is available to watch on YouTube.

The ballet also folds in a fantastical character in the form of a theatrical device: a female dancer portraying Chanel’s shadow, embodying her relentless drive and future success. And though there is triumph in ending with Chanel’s return from exile and to the runway, for Santos, there is also ambivalence.

“My interpretation is quite mixed,” says Santos. “She was able to succeed in the end, but it was a very rocky path.”