Is New York City Still Fertile Ground for Smaller Ballet Companies?

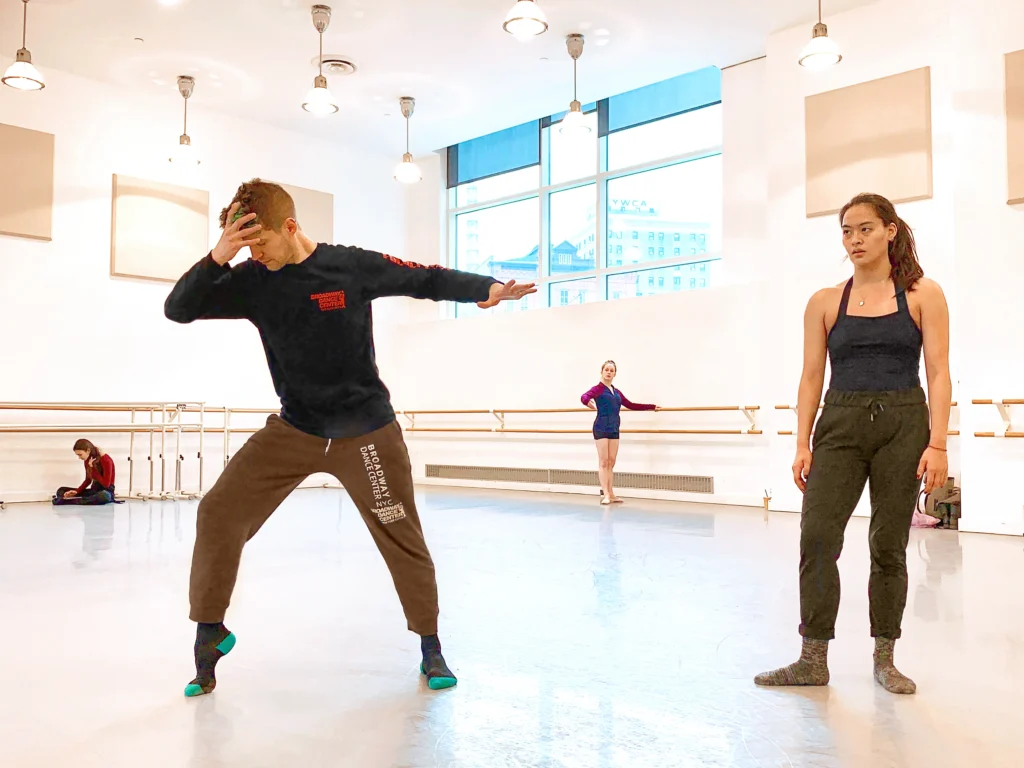

New York City is famous for being a place where one’s dreams come true. I relocated here in 2017 hoping to one day start my own contemporary ballet company. After several years researching the scene, building community, and cultivating the necessary skills, I launched Movement Headquarters in 2019.

Within a year, we had presented multiple well-received productions. Peers expressed curiosity about our work, and professional dancers sent their resumés and attended our classes. My efforts felt as if they were paying off. Yet the greater our success, the more elaborate our programming became—and the more roadblocks stood in our way.

After three grueling years, I made the difficult decision to put Movement Headquarters on hold in early 2022. I had to address financial losses and my own burnout to determine if it was viable to keep my company alive long enough to see it thrive.

New York has long nurtured small troupes from inception to critical acclaim. Yet through my own research, it appears that fewer companies are surviving long enough to flourish. As I stepped back, I spoke with two fellow choreographers who direct their own companies: Morgan McEwen, of MorDance, and Fadi Khoury, of FJK Dance.

Khoury launched FJK Dance, known for ballroom-style performances interlaced with ballet and Middle Eastern culture, in 2014. “I had been in New York for seven years and was auditioning,” he says. “I was rarelyoffered work and, as an immigrant of Arab descent, it was especially hard to feel I belonged.”

For Khoury, who has often felt alienated, his company has been a vehicle to communicate that he is just as human as anybody else. “My story is a New York story!”

McEwen started her contemporary ballet company in 2014. “I was living in New York City dancing with the Metropolitan Opera,” says McEwen. As a young, female choreographer, she had limited opportunities. “I realized I needed to make my own.”

As we spoke, we shared the same struggles with funding, affordability, the press, overwork, and more. And while we’re still inspired to succeed, we wonder what’s still possible in the world’s dance capital.

Funding Struggles

When starting Movement Headquarters, I thought our diverse mix of productions and educational programming would entice both individuals and grantors to fund my company. Yet our funding wasn’t growing fast enough to meet external expectations—audiences wanted more extravagant works and more frequent performances.

Individual donors provided the majority of the company’s income. Corporations want significant benefits for their employees in exchange for funding, and most grantors won’t consider funding dance companies until they have at least three years of tax records and an annual budget well beyond $25,000.

Additionally, most grantors seek applicants whose programming aligns with whatever cause they’re supporting. “It is hard to write details about a program that may or may not be produced,” says Khoury. “There is so much political background in what grantors are looking for, and I can’t afford to pay for a grant writer to help me.”

By 2021, I began experiencing panic symptoms when preparing grant applications. Running my company while doing outside work to cover personal expenses—plus spending hours writing proposals for ballets that were unlikely to get funded—would literally leave me breathless.

Overworked and Underpaid

Artists are often encouraged to include their salary in company budgets. But in reality, most young directors are funding their own productions and putting whatever is left, if anything, back into their organizations. This can mislead the general public into believing that small companies are simply passion projects.

Both McEwen and Khoury paid themselves nothing for nearly seven years.

“I was still dancing for the Opera and teaching to support myself,” says McEwen. The pandemic was a turning point. “I had a child at the beginning of it,” she says. “I needed to keep the lights on and cover childcare expenses.” But she also realized she had to show funders that her work deserved to be compensated. Otherwise, “Why should they fund any other aspect of the organization?”

Additionally, the burnout cycle for directors of small companies can be wildly intense. “Feeling burnt out is a recurring nightmare,” says Khoury.

McEwen acts as executive and artistic director and choreographer, and does marketing, development, and more. “Whenever I get to the point of extreme fatigue, it is usually because the company has grown,” she says. “It’s wonderful to recognize, but I can’t continuously sacrifice my quality of life. Me being burnt out won’t allow me to create great art.”

Unaffordable Theater Spaces

Finding performance space is particularly challenging in New York City. For example, it costs McEwen $20,000 to rent the 700-seat Symphony Space theater on the Upper West Side for four days. “This doesn’t include any other costs of putting on a production,” she says.

When launching Movement Headquarters, I rented the Ailey Citigroup Theater at $6,000 for a one-day, two-show event. Between the theater, rehearsal space, artist salaries, marketing, and production expenses, it cost $25,000. As a brand-new company, I knew we couldn’t replicate this budget until we sustained substantial financial growth. But I felt we needed to be immediately visible to audiences and the press to entice additional funding sources.

Performance venues are so expensive that younger companies frequently must rent less-than-ideal spaces at less-than-ideal times. “We often have to choose between paying premium prices for times that are attractive to audience members versus actually putting on shows,” says McEwen.

And audiences aren’t always receptive to venues outside of Manhattan. In 2021, I was elated to find an affordable performance space in downtown Brooklyn for an immersive Nutcracker—only to learn that many dedicated audience members weren’t willing to travel to another borough.

Press Problems

Previews and reviews help sell tickets and builds interest for funders. Yet enticing the press to review productions by companies that haven’t already received recognition is extremely difficult. Khoury, McEwen, and I have all had instances where no press attended our performances.

“The presence of the press is related to how much money you spend on public relations,” says Khoury. “I only received a review in The New York Times after the support of a PR agency was donated. At any other time, they would not be interested in my work.”

What’s Needed?

When addressing specific needs for a dance company to survive and thrive in New York City, we shared several concerns.

McEwen points to the dwindling supply of affordable rehearsal space: “Most studios we once used no longer exist. And now, affordable spaces with New York State Council on the Arts subsidies”—which provide affordable rentals at $10 an hour—“run out very quickly.”

Khoury adds, “We need to be present in the public eye. And for that to happen, we need better funding and invitations to perform in festival programming at bigger venues.”

As we discussed these challenges, the question remains whether New York City is still tenable for young dance companies. I think about companies like Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet, Jessica Lang Dance, and RIOULT Dance. All made names for themselves on both local and national levels. Yet each shuttered when they appeared to be healthy and growing.

As of today, Movement Headquarters is still on indefinite hold. The dancer in me wants to barrel forward with unstoppable determination. But as I gain experience as an arts administrator, I see the stars have not yet aligned to continue growing a sustainable organization.