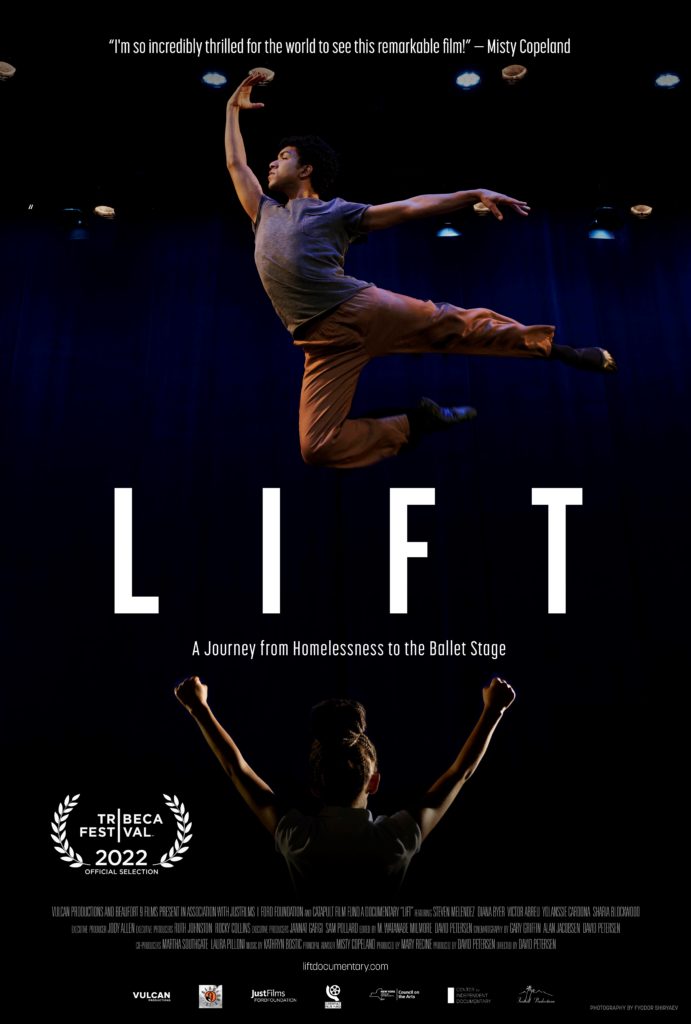

“LIFT” Documentary Spotlights the Impact of New York Theatre Ballet’s Scholarship Program for At-Risk Youth

Steven Melendez’s life sounds like stuff from which movies are made: While living in a homeless shelter in the Bronx as a child, Melendez discovered ballet through New York Theatre Ballet’s LIFT program, which provides scholarships to at-risk children. After an international dance career, Melendez went on to run LIFT—which meant going back to the very shelter where he once lived to recruit participants—and, earlier this year, became the artistic director of NYTB.

Now, Melendez’s story—and the stories of other dancers touched by NYTB’s program—is a movie. The documentary LIFT, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in June, follows Melendez over more than 10 years as he builds relationships with housing-insecure youth through ballet. One of those students: New York City Ballet dancer Victor Abreu, who begins the film at the start of his ballet training and ends it with an apprentice contract in hand.

The film, whose advisors include Misty Copeland and Lourdes Lopez, has been nominated for Shine Global’s Children’s Resilience in Film award, which will hold a screening on September 16. It will then head to the San Francisco Dance Film Festival in November. But its origin was purely happenstance, says Melendez: Director David Petersen, a newcomer to ballet, learned about LIFT while walking his dog in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, where he met fellow dog-walker and photographer Richard Termine, who had shot NYTB. When Petersen proposed the idea of a documentary to NYTB founder Diana Byer, she agreed, understanding his request to be “something that would take 10 days, two weeks, maybe a month,” says Melendez.

In reality, Petersen shot Melendez and the LIFT participants anywhere from weekly to monthly over the course of nearly 11 years, capturing classes and rehearsals, students’ often-challenging home lives, and a triumphant gala performance in 2019.

For Melendez, having his story captured on film—and now sharing that story with the world—felt complicated, especially because early in his performing career he was known as the “homeless ballet child.” “I’ve been running away from that story of myself for a long time,” he says, even moving out of the country early in his professional career to reinvent himself. “So the idea of making a whole movie about it, and leaning into that story, was really difficult for me.”

Melendez even says that after the film’s premiere, his partner of 10 years told him she’d learned more about his past during those 90 minutes than during their whole relationship. “It made me think, How much of this do I hide?” he says. “I want to be sure that my own ego or insecurity doesn’t take away from the potential good that hearing the story might have.”

Abreu, who first appears in the film at age 10, also had a complex relationship to being filmed, especially later as he became more serious about his training. “I got a bit tired, because after 10 years of filming my life, I just wanted to dance,” says Abreu. “It sounds so simple and so selfish. But that’s all I wanted to do.” But he was pleasantly surprised by the story Petersen crafted, and enjoyed reliving early memories of his dance training, even if he says he found watching his own dancing to be “cringe.” Like Melendez, he’s found himself talking more about his background and his experience with LIFT since the film came out.

Melendez wasn’t involved in the editing process, but he says his mark on the film can be seen throughout in how it avoids what he calls “trauma porn,” or the glamorization of homelessness. Though the documentary doesn’t shy away from challenging moments—early on, we see Melendez have a panic attack while visiting the shelter where he used to live, for instance—he says it was important for him to be in conversation with Petersen, who doesn’t have those lived experiences, about what was appropriate to include.

He sees the resulting film as one that doesn’t just speak to the power of LIFT, but to the power of the arts. “There are teachers who think, Every single day I go into work, and I have no idea if it’s making an impact,” says Melendez. “And the reason you can see the impact in the film is because it was shot over 11 years. You can’t tell this story in a snapshot; you need to see the generational difference over time, and you need to see the developments that come from the investment you put in outreach work.”

Melendez hopes to organize screenings at other local institutions doing similar work, “so that the film becomes a universal testimony to all these kinds of programs, not just this one microcosm of magic that happens here in New York,” he says. “I’d like to work myself out of a job—I’d like to make sure that LIFT is no longer necessary in the world.”