After 44 Years, Diana Byer Steps Down from New York Theatre Ballet

“Empty your minds. Only think about the music,” Diana Byer instructs her class of 10- to 13-year-olds on a recent Saturday afternoon. We’re standing in her studio at Dancespace, on the second floor of New York City’s St. Mark’s Church, set back from the bustle of Second Avenue. The space is small, but airy. It’s Byer’s dominion, where the placement of a hand or the angle of an ear can tell a story.

Byer is the founder and artistic director of New York Theatre Ballet, and for the past 44 years she has led her company and its school with the same clear-eyed purpose that she asks her students to bring to their dancing. Byer will step down from her role as artistic director this season following NYTB’s spring performances. Her eight-dancer ensemble will be performing May 4–8 in two programs: a bold, contemporary mixed bill that includes world premieres by James Whiteside and Sir Richard Alston, and a one-hour rendition of Mother Goose designed for young children.

The sheer feat of keeping her small company going over four decades in New York City invites the question “How?” Byer started NYTB in 1978 with a group of dancers who had all trained with Margaret Craske, a disciple of Enrico Cecchetti whom Byer encountered at Juilliard and who became her mentor and close friend. Byer had returned to New York after dancing with Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, not intending to found a company, but wanting to dance. “It was a lark when we started,” says Byer, who performed with NYTB for several years while simultaneously directing it. But the project persisted, through ups and downs, for over four decades. The troupe has since carved a place for itself in New York City’s dance landscape, staging important works by Antony Tudor and Agnes de Mille while championing new choreographers.

“I was just using common sense all the way,” says Byer. However, it required more than the average pragmatism to keep her small troupe alive in a city full of big-fish companies, and much more passion to make it thrive. Her job also requires a great deal of sacrifice and DIY-ing. “My strategy is that I work 14- or 15-hour days. I do.”

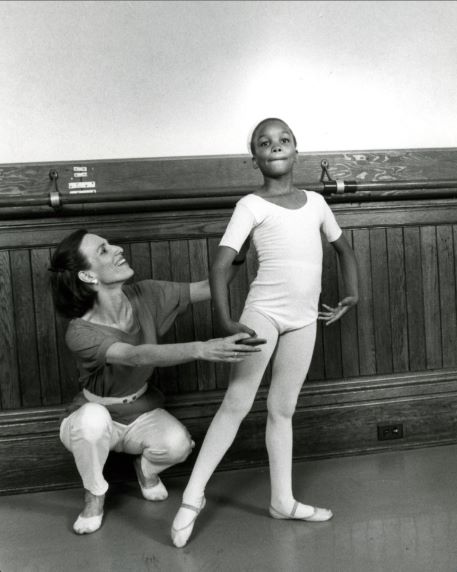

Her determination and common sense have led her to create extraordinary initiatives, like NYTB’s LIFT Community Service Program, which provides dance scholarships to children facing economic uncertainty or homelessness. In the 1980s, NYTB worked with the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs on a residency-like program where children living in shelters would visit cultural organizations over their winter break. “To me there was a flaw in the program, though, because they only got 10 days,” says Byer. “Seeing that flaw, I gave scholarships, and the kids continued. Not only the kids that were the most physically talented, but the ones that had courage and that were smart.”

One dancer who came through LIFT is Steven Melendez, who started training with Byer in 1992 when his family was living in a shelter. Melendez rose to become a principal with NYTB, and will take the reins from Byer as the company’s next artistic director. Victor Abreu, a New York City Ballet corps member, also received his early training through the program. This summer, the documentary LIFT, which features Melendez and Abreu’s inspiring, intertwined stories, will debut at the Tribeca Film Festival.

When Melendez takes the helm of the company, Byer will continue as school director. “It’s really important to me to keep Margaret Craske’s legacy and the way that she taught the Cecchetti syllabus alive,” says Byer. “It went from Cecchetti to Craske to me. It’s so different from the way that dance is taught today. It’s not athletic; it’s about gesture, it’s about use of eyes, and it’s about generosity to the public. I think if we want do ballets by the likes of Tudor and de Mille, if those ballets are going to survive, this way of teaching matters.”

Byer studied with Tudor at Juilliard in the early ’60s, and his teaching had a profound effect on her. “He always said that he didn’t want to see dancers trying to be people, he wanted to see people who happen to dance. That’s what my company is about.” NYTB frequently revives works by Tudor and José Limón, as well as Jerome Robbins, Agnes de Mille and Merce Cunningham. For many years the company has mixed these dancemakers’ smaller-but-established masterworks with new work by emerging choreographers. And their ability to take risks with both types of repertory has been part of NYTB’s magic, winning them critical acclaim and affection from New York’s discerning dance audience.

Byer’s strategy for commissioning new works has been a simple one: going to shows, talking to the folks next to her, meeting choreographers and people who might be interested in the company. For many years, the dance archivist and performer David Vaughan, who died in 2017, was her sounding board. “He would take me to performances and introduce me to choreographers that I would never think of seeing.” It was this way that NYTB commissioned dancemakers like Pam Tanowitz, Gemma Bond, Matthew Neenan and Nicolo Fonte long before their careers blew up.

Throughout her career, Byer has looked for the unique, sometimes subtle, ways that she can share her profound love of dance. She certainly has no plans to stop sharing that love anytime soon. She’ll teach as Craske taught her, and is slowly working out a plan with the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts to record interviews and classes centering on Craske’s work and how she taught the Cecchetti method. “And here’s my real dream,” she tells me, laughing. “I’m out of my mind, but I would like to start a company for dancers 60 years and older, because I think we all still have something to say.”