Rediscovering Madame Mariquita, the Prolific Choreographer Who Helped Modernize French Ballet

If you were asked to name the influential ballet choreographers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, you’d probably list a lot of men: Marius Petipa, Michel Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky, George Balanchine, Frederick Ashton. Maybe, if you really knew your stuff, you’d add Bronislava Nijinska. You wouldn’t be wrong, but there were others, too.

And if you were asked what was happening dance-wise in France at that time, you might say “The can-can!” or “Isadora Duncan,” or “The Ballets Russes came to Paris then, right?” Again, you wouldn’t be wrong. But there was more.

Little known fact: According to research by Sarah Gutsche-Miller, between 1870 and 1920, 26 choreographers created around 600 ballets in 30 Parisian theaters, and of those 600 ballets, more than half were created by women. And of those, the majority were created by one woman: Madame Mariquita.1

Following her death in October, 1922,2 dozens of newspapers in Paris, London, and New York ran obituaries and eulogies honoring the prolific choreographer. They praised her for revitalizing ballet and being a “French Fokine,”3 writing that she would be remembered forever and “her name would remain attached to the history of dance, which she renewed.”4

Sadly, they were wrong about the last parts. For a myriad of reasons, many of us have not heard of Paris’ once-beloved choreographer. But thanks to the pioneering work of two historians, Gutsche-Miller and Lynn Garafola, we are starting to learn more about her.

A Young Talent

Mariquita was born around 1840 in Algeria (the exact date and location are unknown, along with her full name and family origins). She was orphaned at a young age and found—standing by a fountain, the story goes5—by a female dancer who took her in and taught her to dance. After the death of Mariquita’s adoptive mother, an impresario brought her to Paris to further her budding performance career.6

The young Mariquita debuted in Paris in 1845 (by some accounts she was 5 years old, by others 7)7 in a vaudeville production at the Théâtre des Funambules. She quickly made a name for herself and in 1855 caught the eye of Jacques Offenbach, who invited her to perform in his new Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens.8 After receiving focused classical ballet training, she was ready to join the Paris Opérain 1858 at the rank of sujet de la danse. She did not enjoy the rigid, hierarchical culture of the Opéra, though, and soon left for Madrid, where she danced as a première danseusefor several years.9

Around 1860, Mariquita returned to Paris and danced for many well-known theaters: the Théâtre des Variétés,10 the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, and the Folies-Bergère among them. She gained a reputation for being one of the best character dancers around, and an outstanding ballerina.11

From Dancer to In-Demand Dancemaker

In the early 1870s, Mariquita started choreographing light divertissements (short, plotless ballets) for small theaters. She had a knack for it and was soon creating work for popular boulevard theaters and music halls (think of them as the 19th-century French equivalent to off-Broadway and Broadway venues). While choreographing at the Folies-Bergère, she collaborated with conductor-composer Olivier Métra. One of those early works, Les Joujoux (1876), features a fairy doll who awakens toys that dance off the shelves and around the shop. The divertissement was an immediate success and ran on and off for over a year (unusual for the time).12

In 1880, the Théâtre de la Gaîté offered Mariquita the position of ballet mistress, which at that time combined the roles of choreographer, artistic director, and dance teacher. She accepted and kept the position for over 20 years. In 1890, she became ballet mistress at the Folies-Bergère, as well, a position she held until 1913. In 1898, she was approached by Albert Carré, the newly appointed director of the Théâtre National de l’Opéra-Comique (Paris’ second national theater after the Paris Opéra), to be their ballet mistress, too. He wanted to modernize French ballet, and believed she could help him do it.13 She took him up on his offer and remained there until 1920.

This means that Mariquita was the ballet mistress of one of Paris’ top theaters for 40 years straight and, at least for a few of those years, of three of them at the same time. As if that weren’t enough, she was also appointed the official choreographer for the famous 1900 Paris Exposition’s Palais de la Danse.14

A Forward-Thinking Choreographer

While at the Opéra-Comique, Mariquita created nearly 30 ballets and divertissements.15 At first, Gutsche-Miller found, they stuck to the conventions of classical pantomime-ballet, but as she grew more confident, she moved away from the traditions she found stifling. She got rid of what she called the “grotesque” tutus and put her dancers in more “naturalistic” costumes and modern dress.16

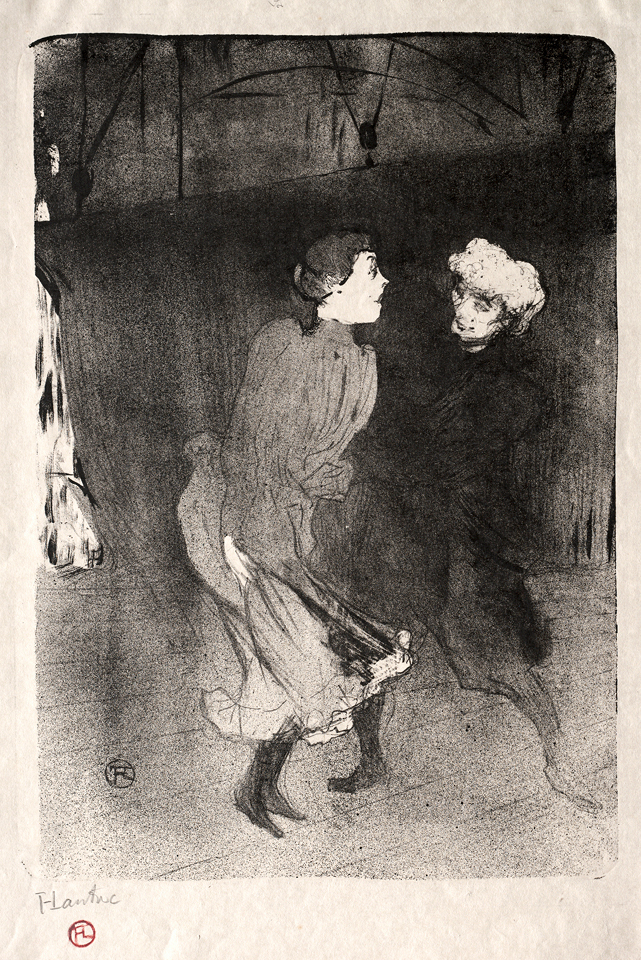

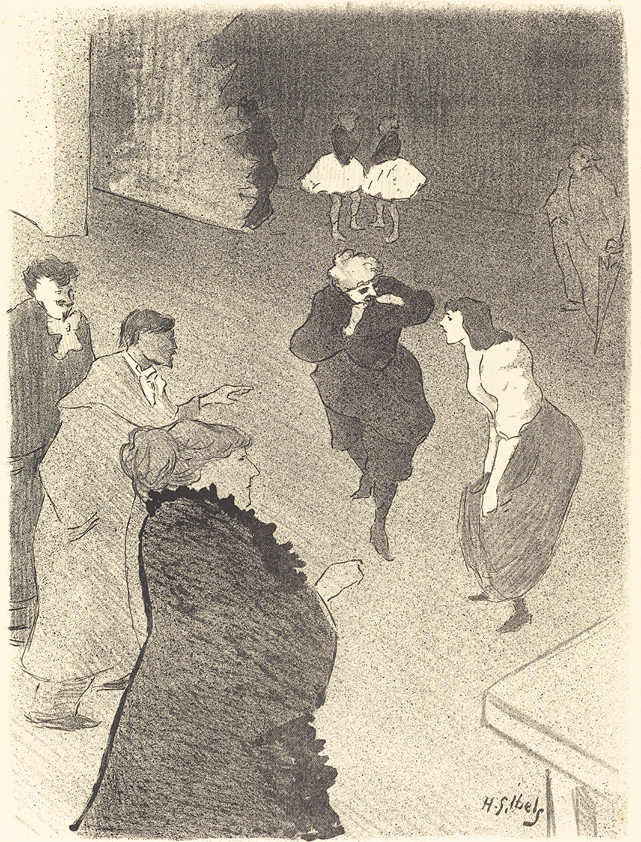

Her ballets often made references to contemporary life.17 Une Répétition aux Folies-Bergère (1890), for instance, offers a behind-the-scenes glimpse into making a ballet, complete with dancers in rehearsal clothes.18 Émilienne aux Quat’z’Arts (1893) parodies a scandalous event that had occurred at an art-school ball earlier that year, involving the crowning of a scantily clad beauty queen. In Sports (1897), a woman leaves her husband behind to pursue athletics.19 Her ballets evolved to have more developed and complex storylines.20 (Mariquita was one of the first choreographers to be acknowledged as an “author” of her choreographic work; she was inducted into the Society of Dramatic Authors and Composers in 1890, allowing her to receive the royalties she deserved.)21 She removed the showy acrobatic sequences typical of classical ballet at the time. As Gutsche-Miller argues in “Limitations of the Archive: Lost Ballet Histories and the Case of Madame Mariquita,” she even experimented with “free dance” inspired by Ancient Greek statues and frescoes starting in 1899, before Duncan or Nijinsky ever stepped on a Paris stage.22

Stylistically, Mariquita started blending her worlds—infusing her classical ballets with popular dance forms and trends (including a little bawdiness) and bringing classical structure and technique to her music hall productions. While reading through contemporaneous reviews in the press, Gutsche-Miller and Garafola both found that the results were a win–win: Mariquita helped raise the caliber of theater dance and widened the appeal of high-art ballet. For this she was adored by critics and audiences alike.

Rediscovering Mariquita’s Legacy

As Gutsche-Miller argues in “The Limits of the Archive,” fin-de-siècle Paris has long been glossed over as a dark period, or at least a dim one, for French ballet. The Paris Opéra created very few ballets during those years (only seven premiered between 1890 and 1905) and, according to critics at the time, most of them were lackluster.23 But, as Gutsche-Miller explains in “Mariquita, the French Fokine,” to say that the arrival of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes to Paris in 1909 was what saved French ballet is incorrect.” Mariquita had been steadily modernizing ballet since 1871.24 Thanks to her, audiences were already primed and ready for what was to come.

As to why one of the most prolific and celebrated ballet choreographers has been overlooked in dance history, there are many possibilities: As Gutsche-Miller points out, she was reluctant to talk to the press and didn’t promote herself or her art as Duncan and Diaghilev did.25 She also worked in venues that weren’t taken as seriously and weren’t as well documented as the Paris Opéra.26 I would add that she was an Algerian-born woman in a European, male-dominated art form.

But Mariquita is rising up from the archival ashes. This is not unheard of in the world of ballet—ghosts and phoenixes run rampant. Not in Mariquita’s storylines, though. She preferred her characters alive and well.

__________________________________________

Editor’s note: Updated on 3/18/24 to include endnote citations.

1 Sarah Gutsche-Miller, “The Limitations of the Archive: Lost Ballet Histories and the Case of Madame Mariquita,” Dance Research Volume 38 Issue 2 (2020): 301.

2 Sebastian Voirol, “Mariquita, an Appreciation,” Dancing Times 146 (November 1922): 119.

3 Sarah Gutsche-Miller, “Madame Mariquita, the French Fokine,” Topographies: Sites, Bodies, Technologies, Thirty-Second Annual Conference Stanford University & ODC Dance Commons Stanford & San Francisco, California 19-22 June 2009, p. 106.

4 Sarah Gutsche-Miller, “Madame Mariquita, Greek Dance, and French Ballet Modernism,” Dance Research Journal 53, no. 3 (2022): 46.

5 Michel Carré, Souvenirs de théâtre (Paris: Plon, 1950), 219.

6 Sarah Gutsche-Miller, Pantomime-Ballet on the music-hall stage: The popularization of classical ballet in fin-de-siecle Paris (McGill University: Doctoral thesis, 2010), 149.

7 Sarah Gutsche-Miller, Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913, (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2015), 308.

8 Voirol, “Mariquita, an Appreciation,” 119.

9 Gutsche-Miller, Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913, 71.

10 Lynn Garafola, Legacies of Twentieth-Century Dance, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2005), 217.

11 Gutsche-Miller, Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913, 71.

12 Gutsche-Miller, “Madame Mariquita, the French Fokine,” 103.

13 Gutsche-Miller, “The Limitations of the Archive: Lost Ballet Histories and the Case of Madame Mariquita,” 303.

14 Gutsche-Miller, Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913, 71.

15 Garafola, Legacies of Twentieth-Century Dance, 217.

16 Gutsche-Miller, “The Limitations of the Archive: Lost Ballet Histories and the Case of Madame Mariquita,” 303.

17 Gutsche-Miller, “Madame Mariquita, Greek Dance, and French Ballet Modernism,” 47.

18 Gutsche-Miller, Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913, 60.

19 Gutsche-Miller, Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913, 173.

20 Gutsche-Miller, Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913, 72.

21 Gutsche-Miller, Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913, 302.

22 Gutsche-Miller, “The Limitations of the Archive: Lost Ballet Histories and the Case of Madame Mariquita,” 303.

23 Gutsche-Miller, “The Limitations of the Archive: Lost Ballet Histories and the Case of Madame Mariquita,” 299.

24 Gutsche-Miller, “Madame Mariquita, the French Fokine,” 1.

25 Gutsche-Miller, “Madame Mariquita, Greek Dance, and French Ballet Modernism,” 50.

26 Gutsche-Miller, “The Limitations of the Archive: Lost Ballet Histories and the Case of Madame Mariquita,” 297.