The Genée IBC Is Back—With a New Name and a New Way to Watch

Like most every other event of last year, the Royal Academy of Dance’s Genée International Ballet Competition was canceled in 2020, put on pause during the first waves of COVID-19. Its suspension was an especially heavy blow; the organization was marking its 100th anniversary and had just announced plans to change the competition’s title to the Margot Fonteyn IBC in celebration.

Now, after a year of waiting, the Fonteyn is finally here—and this time the new name also brings an entirely new online format, with a digital performance final on September 9 that will be available to watch until the 19th.

The changes opened doors to a record-breaking 97 participants and allowed for the competition’s coaching sessions—usually held the same week as the performances—to occur over Zoom several months in advance.

For Olivia Chang Clarke, the 2021 Choreographic Award recipient and a competition finalist, the new format helped her better develop her dancing for this year’s Fonteyn. “I had only really just started developing the solos,” she says, “so those corrections I had at the beginning I could continue to use through the process.”

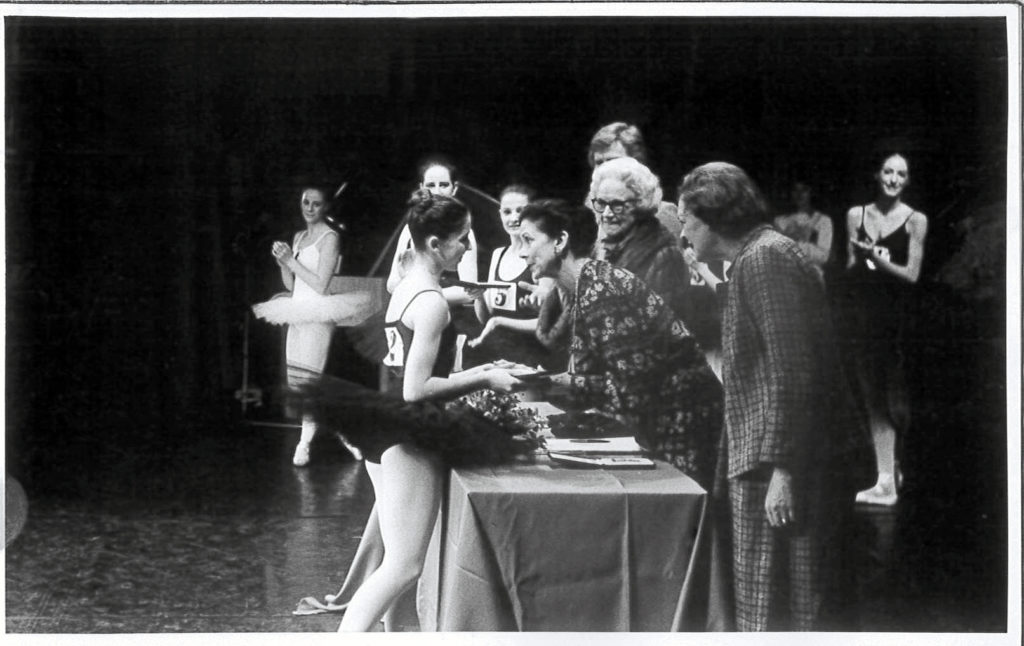

One of those coaches was former Royal Ballet principal Leanne Benjamin, who, in 1981, won the Genée when she was only 16. Onstage to present her the award was Dame Margot Fonteyn herself, ballet legend and then-president of the RAD who was there as a judge.

In a diary entry from that day, which Benjamin now reads aloud in a video released by the RAD, she wrote about the way Fonteyn’s presence made her dance even better. “How lucky could I be,” she wrote. “I kissed her when she gave me the medal.”

“She was so iconic,” Benjamin told Pointe. “She held herself with such authority and grace.” It’s that legendary status that inspired the RAD to change the Genée’s name.

“For most iconic dancers there’s only a certain generation who know who they are,” says Gerard Charles, artistic director of the RAD, “but Fonteyn is such a household name. She embodied qualities as an artist that today we would still benefit from emulating.”

Clarke agrees: Even to her generation, she says, “Margot Fonteyn is the person of ballet.”

After the coaching sessions earlier this year, participants filmed and submitted a classical and contemporary solo. Judges then watched each recording once and chose 15 finalists. The selected group worked over Zoom with choreographer Ashley Page to learn a commissioned solo which they submitted along with their classical entry—both will stream during the finals.

For Benjamin, the expansion of opportunities afforded by the new format is an echo of Fonteyn’s influence. “She wasn’t just inspirational as a ballerina,” says Benjamin, “she was interested in helping the younger generation, in being a great educator.”

Going forward, Charles wants the Fonteyn to embody a lot of positive change; he hopes the competition will be able to occur in person for 2022, but will continue to monitor the situation given that the event usually draws students from dozens of different countries. Nevertheless, the RAD is set on learning from the successes of this year. The earlier coaching and lessened need to travel allowed more students to benefit from the competition’s educational opportunities. “One of my big goals is to make it more than just about the lucky few,” says Charles. “I want to look to enhance those opportunities for next year.”