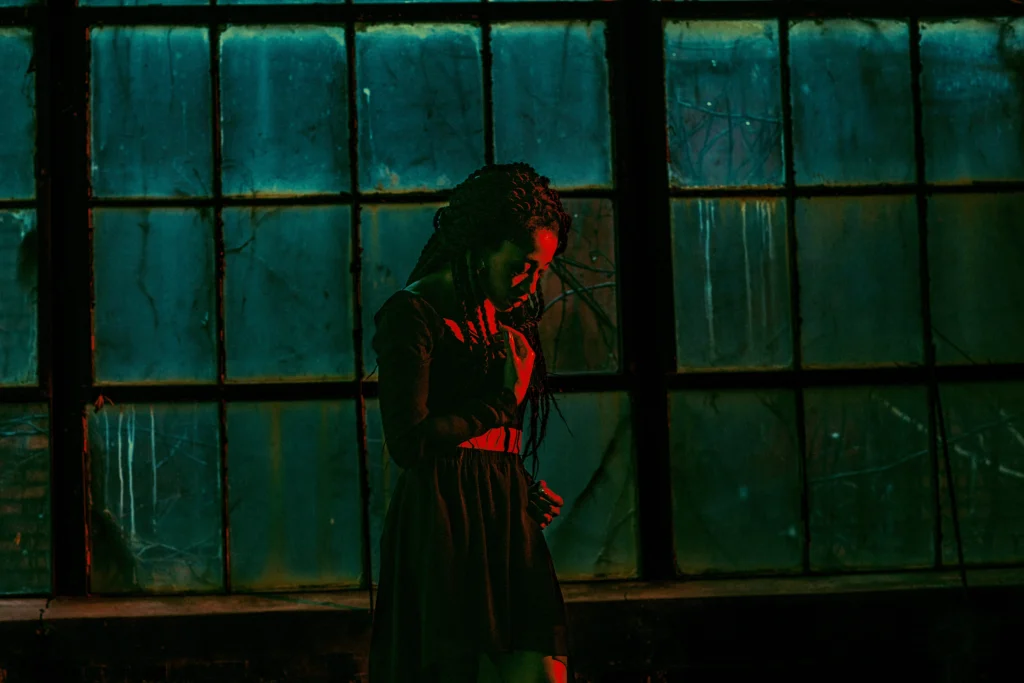

BalletMet’s Rachael Parini Opens Up About Living With Bipolar 1 Disorder, and Her Triumphant Return to Dance

In the summer of 2022, BalletMet dancer Rachael Parini began to experience symptoms of bipolar disorder, a mental health condition characterized by episodes of mania or hypomania and depression. Parini was diagnosed with bipolar 1, which is determined following a manic episode lasting a week or requiring hospitalization, along with a major depressive episode. (Bipolar 2, which is a less severe form of bipolar disorder, is diagnosed after at least one major depressive episode and a hypomanic episode, which are less extreme than manic episodes and do not include delusions or hallucinations.) The symptoms associated with a bipolar diagnosis can be frightening, damage relationships, affect work performance, and impact finances.

After a year of treatment and understanding this disorder, Parini opened up to Pointe about her experience and her slow return to ballet. —Linnea Swarting

In June of 2022, during BalletMet’s summer layoff, my husband and I had just moved into a new home. I said I was “redecorating” the house, but, really, I was experiencing my first manic episode. I moved our furniture morning, noon, and night; I didn’t sleep for seven days straight and started hallucinating. I was also dressing in loud outfits that I wouldn’t have normally put together—I had never felt so confident and beautiful. I was absolutely euphoric! But I also experienced terrible mood swings and insisted that my husband be home with me. One day, while organizing the basement, I became violent towards him. My brother-in-law is a doctor and advised my husband to take me to the hospital right away. Once there, I was “pink slipped” (placed in a psychiatric facility involuntarily) for attacking my husband.

My first hospital visit lasted three days. I began treatment for bipolar 1 and was given medication to subdue my symptoms. But the drugs made me lethargic, and, not understanding the severity of my illness, I stopped taking them. My family came to visit for Fourth of July and could tell something was still off. I began impulsively spending money, a symptom of mania. I spent $20,000 over the course of two months. I also became hyper-religious; it felt good to reconnect with my faith, but in reality I was avoiding consequences, believing that God would protect me. I started having dangerous ideations about harming myself and my husband. I realized I needed to go back to the hospital; I was in psychosis.

My second hospitalization led to new medication. I was released but still experiencing symptoms of mania, and I became delusional. For instance, I developed a fear of mirrors, convinced someone was staring back at me, and made my husband remove or cover up all the mirrors in the house. I cut off chunks of my hair. One day I got into a small car accident after driving recklessly. The next day I started arguing with my husband about race in America and became so emotional that my mother-in-law came to help de-escalate the situation. They called the police and, in my volatility, I assaulted and injured one of the officers. My husband begged them to recognize I was having a mental health crisis, and they took me to the hospital. There, I was struck with the desire to dance and choreograph. I made a costume out of my hospital gown and performed for the extremely kind nurse, writing down all my choreographic ideas with a paper and crayon.

That third hospital stay was difficult—I became a target of racial harassment by a fellow patient, and another attempted to sexually assault me. I didn’t feel safe at all, and the hospital didn’t rectify that situation. My husband took me to OSU Behavioral Health, where I was finally put on lithium. It helped, but it made me nauseous. My psychiatric nurse eventually put me on new medication that stabilized me to the point where, by February, I felt ready to return to BalletMet.

As I prepared to come back, I experienced crippling anxiety. My co-workers were so supportive, and artistic director Edwaard Liang and executive director Sue Porter had been checking in with my husband while I was out. Despite this, I experienced serious panic attacks and decided I wasn’t ready to return to work. This began my first major depressive episode. I became suicidal and began giving away my prized possessions because I thought I was going to die soon. Thankfully, my psych nurse was able to provide medication that pulled me out of it. It was enough to make me try again. My goal was to be in my friend Leiland Charles’ new piece, Decisions, Decisions, in March, but I realized I was too far behind in my pointework. I ended up just participating in the process and not performing, which helped me get reacclimated to the environment. I was feeling better, I thought—taking class, attending rehearsals, and going to the theater with everyone.

The next performance was Swan Lake, and I was cast as a cygnet. It was challenging mentally and physically. During one cygnet rehearsal, I struggled to hold myself together; Edwaard happened to be watching and pulled me aside. He said, “Don’t worry, this is a hard ballet for everybody, but I know you’re strong enough to do it.” Despite his encouragement, at the end of that rehearsal I broke down crying and went home. I wasn’t ready to return, no matter how much I wanted to be.

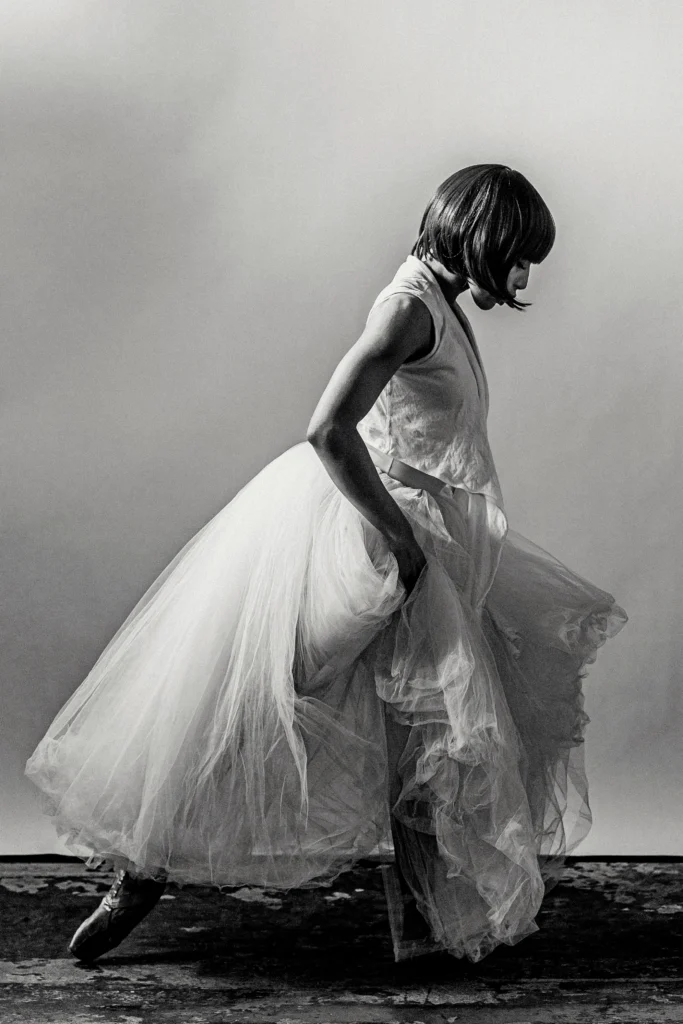

At that point, I worried I might never get over my anxiety. My last performance with BalletMet, in May of 2022, had been Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain pas de deux, and it might have been the best thing I’d ever done. I thought, If I can’t dance again, at least I did that.

I told my psych nurse that I thought my career was over and I was in another major depression. She suggested another medication change this past April, and we started trying different options. Finally, this summer, we got it figured out, where I feel like myself again. (I still follow up with my psych nurse and have biweekly therapy sessions, which helps a lot.)

That’s when I started getting excited about going back to dance. I began stretching, rolling out, and working on my alignment at home. And I’m happy to report I’ve been doing really well since the season started! I’ve been cast in all three ballets of the first program, and the artistic staff seems happy with my work. I’ve never been more thankful to be able to wake up and dance. I’ve been through something life-changing that very few people in the ballet world (that I know of) can relate to. Instead of feeling like my career is over because of this diagnosis, I feel that, because I learned to cope with it, my career has been given a new life.

I can’t begin to describe how thoughtful everyone has been at BalletMet. Edwaard would text me, and my husband was in touch with Sue a lot. They showed me how much they missed my presence. They renewed my contract, and Edwaard kept me on the cast list whenever possible, because he didn’t want me to feel like I was being replaced while I took time to get treatment. My friends checked up on me constantly—it really speaks to BalletMet’s culture of being a family.

For other dancers going through a mental health challenge, the most important thing is having a good support system. I’ve been incredibly fortunate, because I could have done serious damage to my relationships; I’m responsible for all those things I did and said during my manic episodes, and I’m so grateful that I’m surrounded by such patient people. Another thing critical to my recovery was knowing when to ask for and accept help. I think there are too many of us who are afraid to ask, especially when it comes to mental health—it can feel like succumbing to a stigma or admitting defeat. But really, it’s the first step to getting better.