The Surprising Cross-Training Benefits of Rock Climbing for Ballet Dancers

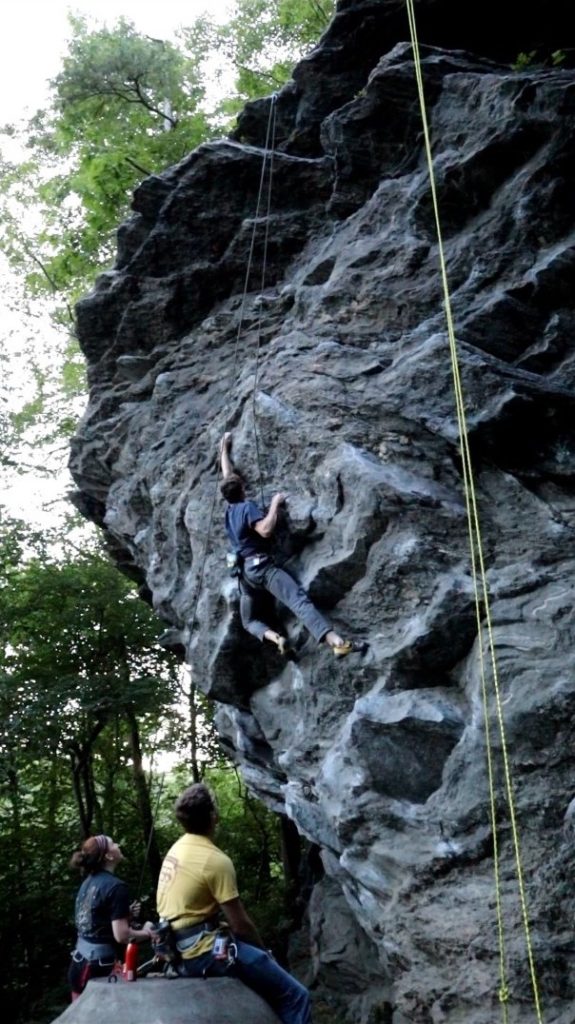

At first glance, a vertical rock face and a theater have little in common. But as diverse forms of cross-training become the norm for ballet dancers, some have turned to rock climbing as a way to supplement their in-studio training and condition their bodies for partnering. Along the way, they’ve been surprised to learn that these two forms complement each other better than they could have imagined.

“Rock climbing’s a really good exercise for the brain, but it’s also a great upper body and leg workout,” says Henry Griffin, a Boston Ballet II dancer who was introduced to rock climbing while living with his family in Philadelphia during the pandemic shutdown. “It’s a good training tool because onstage or in rehearsal you have to be calm and ready for whatever’s going to happen. That’s the way the techniques intertwine: problem-solving under muscle fatigue in a stressful environment.”

Becoming a Better Partner

One of the first transferrable benefits that Griffin noticed from rock climbing was how it helped him activate and strengthen the smaller muscles in his arms and back. Back in the Boston Ballet II studios, he realized that was going to give him a leg up with partnering. While rehearsing a pas de deux from Don Quixote that ended with a much-feared press lift, Griffin, who likes to climb both outdoors and at a gym, did some of his conditioning for the difficult move at an indoor rock wall. “I’d force myself into a really tiring position and lock things off, and then go to the next move really calmly and efficiently even while shaking,” he says. “That translated to the studio; the first time I did the lift I was shaky, but I had the mindset ready to calm down and push through without hurting myself or my partner.”

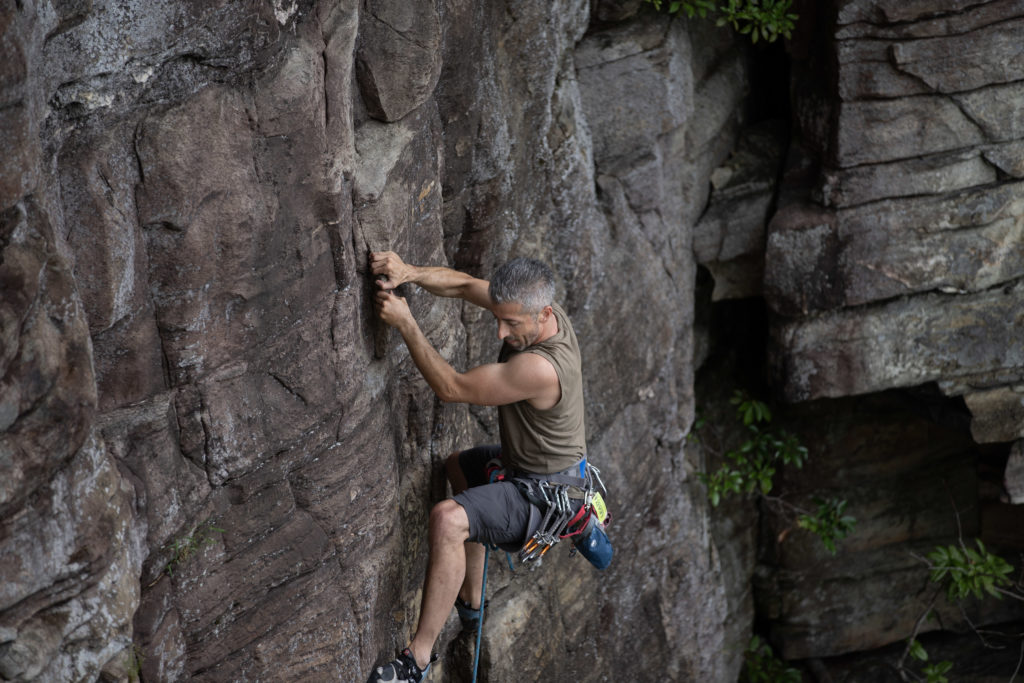

Jared Redick, the assistant dean of ballet at University of North Carolina School of the Arts, turned to rock climbing seven years ago, after moving to North Carolina. “What I struggled with at the beginning—after partnering for so many years—is the pulling motion of climbing, as opposed to pushing,” says Redick, whose resumé includes soloist positions with Boston Ballet, Miami City Ballet, The Suzanne Farrell Ballet and more. Most climbing above 20 feet off the ground involves belaying, which uses a system of harnesses and ropes that creates tension as climbers pull themselves vertically upwards. “You’re using the opposing muscles, which ultimately help strengthen each other,” says Redick. Bouldering, a freeform style of climbing at lower heights, doesn’t use any tools, forcing practitioners to rely more on full-body strength.

The Lower Body

The physical crossovers between climbing and ballet go beyond just the upper body. Rock climbing tends to require the legs to be in parallel or turned-in positions, which strengthens the internal rotator muscles and can help with turnout in the studio by creating a more balanced musculature. This kind of conditioning can also be advantageous to dancers tackling turned-in contemporary work. “There’s more static movement in rock climbing than in dance,” says Boyd Bender, a physical therapist who regularly works with both rock climbers and Pacific Northwest Ballet dancers. “You’re using the entire hip musculature to brace yourself.”

Griffin has found that climbing has strengthened his feet, calf muscles and shins, as well; he remembers many a tricky climb where his “calves were on fire” afterwards. “You think you’d want a lot of surface area on the wall, but sometimes you just want as little connection as possible, and push from there,” says Griffin, who notes that the high arches and flexibility celebrated in ballet create an advantage here. “Sometimes I’ve been in almost a full split and am able to pull the rest of my body onto one leg,” he adds.

Time Under Tension

When it comes to rock climbing, the mind–body connection is just as important as physical strength. Redick relies on self-assessment, body awareness, flexibility and visualization skills he learned from dance training to make him successful as he determines his path up a rock face. “You have to imagine how the movements would work, which is kind of similar to thinking through a variation,” he says. “There’s a very cerebral, intellectual approach to climbing. You can’t just brute-force it.”

Griffin refers to this state as “time under tension.” “It’s really meditative,” he adds. “You’re breathing the whole way through it. It’s physical exertion, but you also have to be calm and rely on your stamina to finish the climb.” Griffin has learned to apply that same approach to performing: “When you’re fatigued, the clearer your head, the easier it is to deal with.”

Myth Busting

Some may think that sports like rock climbing create a bulky physique, but Redick says that’s a misconception. “Elite climbers with huge muscles look that way because they do supplemental weight training, but I see great climbers of all genders who don’t look that way,” he explains. “Climbing can be a great tool to gain more of a sense of what you need to work on in the dance world,” adds Bender, noting that it can reveal areas of weakness.

Perhaps the most common concern associated with rock climbing is that it’s dangerous. “I’m probably more prone to injury in the studio that I am from rock climbing,” says Griffin, who adds that he often has to reassure his ballet teachers that he climbs with a rope and harness. Redick adds that bouldering, although you’re closer to the ground, is more dangerous than rope climbing, because you’re not tied in.

“If you have a big performance coming up, I wouldn’t push it, but climbing is a wonderful aerobic activity that gets you out of your head,” says Redick. “You’re doing something physical, but it has nothing to do with whether you’ve hit that fifth position or stuck the double tour. Instead, it’s like ‘Oh, I fell off the climb. Big deal. I’ll get back on and try again.’ ”

Want to Try Climbing?

If rock climbing has piqued your interest, Redick recommends finding a local indoor climbing gym and signing up for a beginner’s class or asking to work with a more experienced climber one on one. “And bring a friend,” he says, “because then it becomes even more fun.”