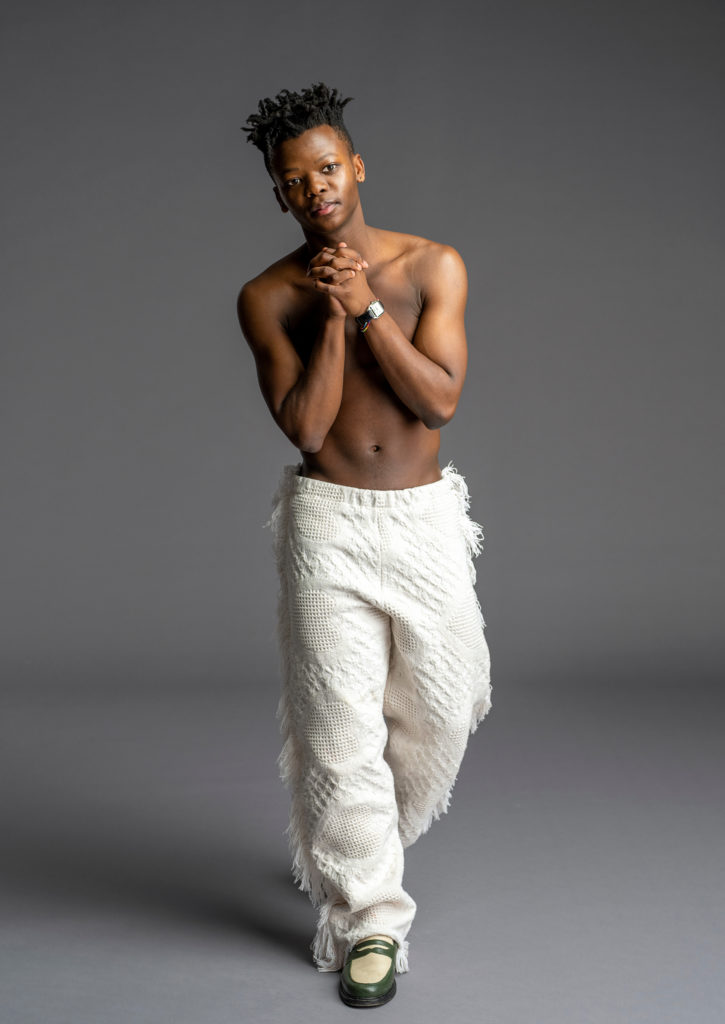

Siphesihle November, National Ballet of Canada’s Charismatic New Principal, Has Captured Toronto’s Heart

When the National Ballet of Canada returned to the stage last fall after 20 long months of pandemic lockdown, the joy and relief front of house were palpable. According to dancer Siphesihle November, the emotion was similar both onstage and behind the curtain: “There was magic in the air.”

There’s magic, too, in November’s meteoric rise through NBoC’s ranks and into the hearts of ballet fans. In June 2021, the company’s outgoing artistic director, Karen Kain, announced November’s promotion to principal dancer. Just 22 at the time, the South African native shares the title of “youngest ever” with another National Ballet bright light, Guillaume Côté. “Siphe is one of the most special and unique talents that has come along in a very long time,” says Kain. “He’s an incredible contemporary dancer alongside his classical ballet chops; he can switch back and forth more easily than most dancers.”

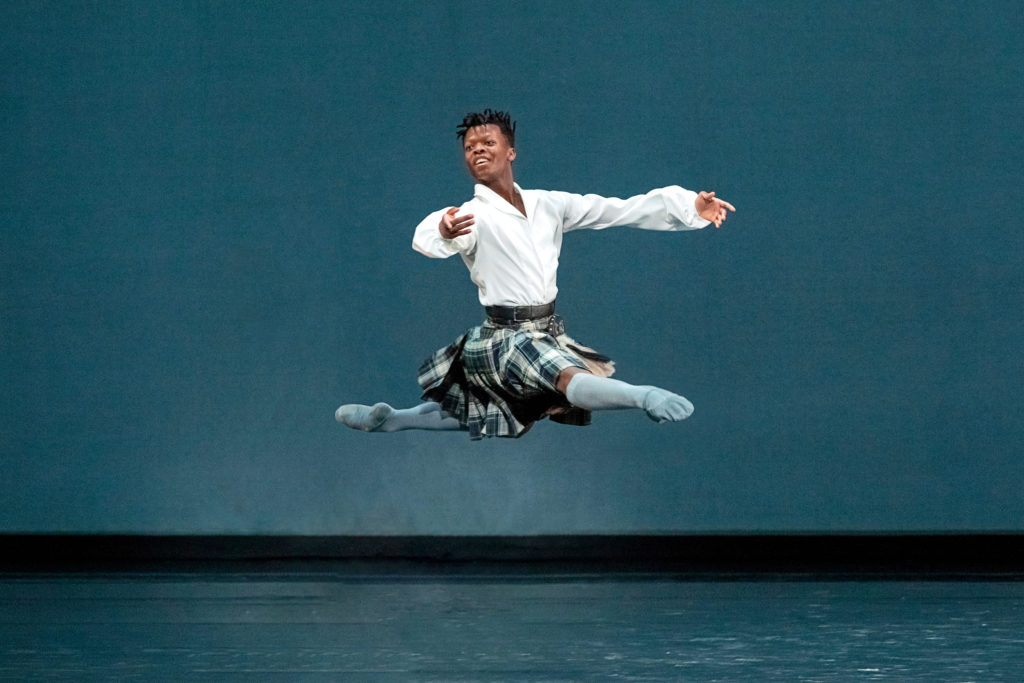

November’s versatility was on display that extraordinary fall night as he danced a crucial role in Crystal Pite’s transcendent group work, Angels’ Atlas. It was his first performance as a principal, in a role that had been created on him by the choreographer. The unforced nature of November’s movement and a glowing, yet not overpowering, presence onstage makes this born soloist a valuable ensemble member, too. In his work with Pite, he exhibits an emotional depth that, along with other gifts—an angelic face, innate musicality—contributes to undeniable charisma. Then there’s the solidly elegant technique that has fueled star turns as Bluebird in The Sleeping Beauty, Puck in Frederick Ashton’s The Dream and Lewis Carroll/White Rabbit in Christopher Wheeldon’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. On top of all this, he’s a budding choreographer. It’s not surprising that audiences and critics love him.

As a new principal, November (who was preparing for his debut as Peter/The Prince in The Nutcracker, the latter performances of which were sadly canceled due to COVID-19) says he appreciates the extra time available to really focus on developing a role. “And there’s a different kind of stamina you need to have. But it’s about expectations, too.”

From Zolani to Toronto

November has been gracefully grappling with other people’s expectations for most of his life. His origin story is gripping—and well documented. Vikram Dasgupta’s 2019 film Beyond Moving chronicles November’s South African roots in his hardscrabble hometown of Zolani. There, November and his four older siblings danced kwaito and other Afro–hip-hop styles at home and in the street. Fiona Sutton, a local RAD teacher who saw the dance potential in the November brothers, roped them into the ballet classes she was teaching in nearby Montagu.

A serendipitous introduction to visiting Canadians, veterinarian Scott Mathison and midwife Kelly Dobbin, whose 5-year-old daughter also took Sutton’s classes, further determined November’s future. With November’s mother’s blessing, Dobbin engineered an audition with Canada’s National Ballet School. November then spent a summer in Toronto training before being accepted as a resident scholarship student with the prestigious school. Just 11, he left Zolani and moved in with the Mathison-Dobbin family. Flash forward to 2017 when, newly graduated, November joins the National Ballet, age 17, no apprenticeship period required—it seems Kain had had her eye on him for some time.

“A Depth of Character”

An exceptional natural mover in a range of styles, November, who won the 2019 Erik Bruhn Prize, has nonetheless fully embraced the classical form. “It’s challenging in a way you can’t really get in any other dance form,” he says. But even with all the time and passion he invested training at NBS, November says that he never took a ballet career for granted. With his shorter stature (he’s now 5′ 7″) and his background, he wasn’t sure he could even have one: “For me, there was this idea that it wasn’t ever for someone like me.” November says that helping to disrupt that kind of thinking is part of what motivates him to keep pushing. “It keeps me going, this barrier to break for so many things. Ballet has such a huge history and I feel being part of it is a huge privilege.”

November will contribute a new chapter to that history as a person of color and principal dancer with a major North American ballet company (only the second Black principal, after Kevin Pugh, in NBoC’s 70-year history). The idea that he will soon tackle the great principal roles of the classical canon thrills November’s Toronto fans. As for what roles and choreographers he’s excited about, November says, “I want to do it all. I’d like to work with everybody! It’s important to me to do lots of different work at the highest level—it’s the only way to grow.”

November believes he wouldn’t be where he is without Kain’s mentorship: “Every step of the way, her vision for me has always been clear, even when I didn’t see it at the time.”

Kain respectfully disagrees: “I think his talent would get him very far wherever he was.” His rise has been fast, but warranted. “Some people need a bit more time to have more confidence or experience,” Kain says, “but Siphe has been ready for all the opportunities, and he is humble about his undeniable talents. There’s a depth of character. I think it’s his time.”

Creator and Innovator

As his career continues to soar in the classical arena, November’s South African roots remain a personal touchstone. He tries to get back to visit friends and family at least once a year. November also spends time in the UK, where his older brother, Mthuthuzeli November, is a dancer and choreographer with London-based Ballet Black. Most recently, the pair collaborated on the contemporary duet My Mother’s Son, filmed in the Battersea Arts Centre for Fall for Dance North, and now streaming on MarqueeTV. The brothers’ early immersion in traditional African dance and music, and fusion street-dance forms, will inevitably infuse the work November is currently choreographing on the National Ballet, his first commission for the main company. (He choreographed a piece for NBoC apprentices last year.) A 20-minute dance for nine performers, it will premiere in March.

“It wasn’t my first instinct to use a classical vocabulary,” he says of the work-in-progress. “I’m not sure why that is, but there’s this mixture of things that inform my dancing—classical technique, contemporary dance and traditional African stuff. I’m trying to blend all these qualities into a hybrid situation. That’s really an extension of who I am, so I’m leaning into it.” The work will feature a traditional African song as part of the soundscape, and costumes designed by November himself.

“There isn’t a clear narrative arc to it,” he tells me, describing the dance as “uncluttered.” “The margins of extremes, physical and visual, are not very big, on purpose.”

The goal? To produce the kind of very human exchanges that dance does best. “It’s important that we create something that invites the audience to learn more about us and who we are as individuals,” says November. “And that may inspire them to interrogate something in themselves, to leave the theater questioning, or even just feeling a way that nothing else has made them feel.”

A quiet insistence that equity in classical ballet can also be nudged along by truly appreciating what each individual performer brings to the table underlines November’s overarching ethos of art. And he believes that classical ballet is more resilient than some people give it credit for.

“I think the art form may breathe new life because of all the changes that are happening,” he says. “We think it’s static because of what we’ve seen before. I’m not here to change the art form, but we all come from different backgrounds and our presence is informed by that. So, what does it mean to carry that onto the stage? I want to show that anything is possible. That excites me.”