Ballet Dancers Conquer Their Toughest Role: Running the NYC Marathon

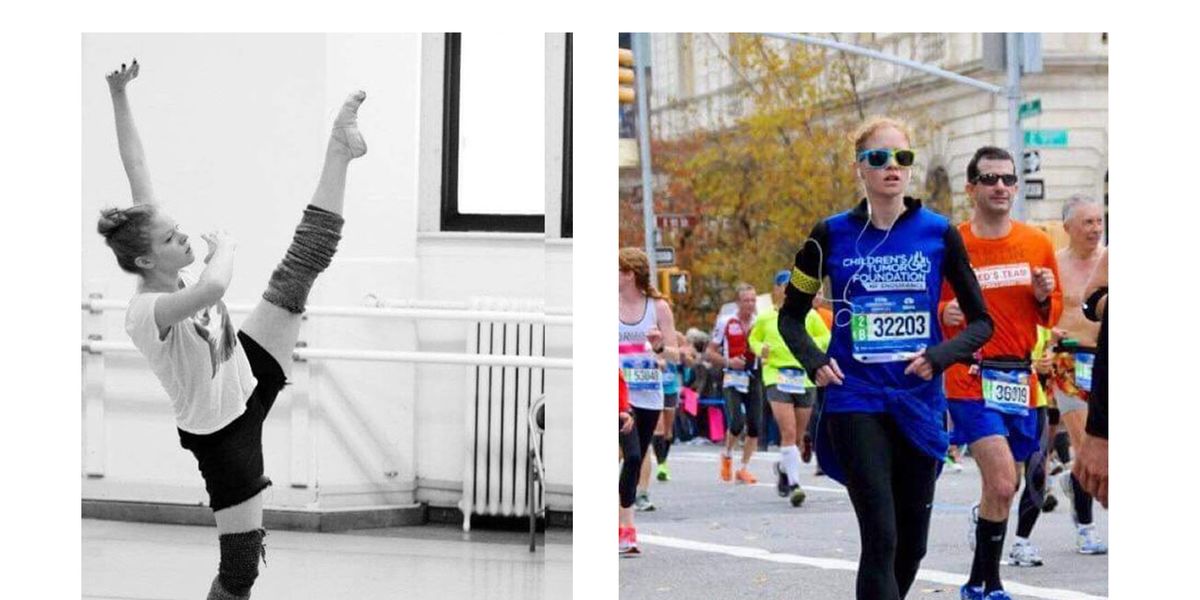

When Erin Arbuckle takes ballet class wearing her New York City Marathon shirt, teachers often ask her, “You didn’t actually run that, did you?” She did, twice, and she’s running again this year on November 5.

Arbuckle, 28, a graduate of School of American Ballet and a freelance dancer who has performed with Ballet Next and Emery LeCrone Dance among others, is a rare ballerina who not only runs but has taken on the challenge of a marathon.

“If I can run 26 miles, I can handle a two-minute variation,” she says.

Ballet dancers are taught to save their bodies for dance and avoid injury from other activities. While low-impact cross-training like swimming is encouraged, running is generally considered too high impact.

“I was told it would give me huge calves and thighs and damage my knees,” Arbuckle says.

Her two foot surgeries were from dance injuries though, not running, and her body is holding up well despite what she was told to expect.

Marika Molnar, director of physical therapy at New York City Ballet, generally advises dancers to run only as a warm up. “Running for 5 to 10 minutes before ballet class to move the large muscles of the body is useful,” she said. “Beyond that, you start to have risks.”

Given the stigma, it’s not surprising that many ballerinas wait to run a marathon until after hanging up their pointe shoes.

From left: Waters and Meredith Rainey in Hawley Rowe’s “#3” while at Pennsylvania Ballet. Photo courtesy Waters; Running the France Run 8k in 2017. Photo courtesy Game Face Media.

From left: Waters and Meredith Rainey in Hawley Rowe’s “#3” while at Pennsylvania Ballet. Photo courtesy Waters; Running the France Run 8k in 2017. Photo courtesy Game Face Media.

Emily Waters, 35, who danced for 10 years with Pennsylvania Ballet and Royal Danish Ballet, is running her first marathon this year. She struggled her entire career with back pain caused by scoliosis and ultimately stopped dancing because of it. She’s been training for the marathon since February and says her back hasn’t bothered her.

Her physical therapist Prachi Bakarania, a back-pain specialist at ColumbiaDoctors, says that running can help with pain management. “The impact of running can improve bone density, as long as training is done correctly and ramped up over time,” she says.

Though Molnar agrees with this in general, she maintains that the length of a marathon can break down the bones, and isn’t necessary for building the type of endurance dancers need. “You dance in spurts, not constant low-low dancing. It’s more like sprinting than a marathon,” she says.

Waters, who now works at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in arts and culture granting and is a graduate student in arts administration at Columbia University, says that marathon training provides the physical exertion she’s missed since retiring from the stage seven years ago.

“When you’re dancing, you’re always taking stock of your body, noticing your aches and pains and responding to them. It feels so good to have that back again,” she says.

Arbuckle finds the satisfaction of the marathon similar to performing. “When you’re standing on the Verrazano Bridge, you know what’s coming, it’s emotional,” she says, comparing the start of the NYC marathon to waiting in the wings to perform.

Peter Boal, 52, artistic director of Seattle’s Pacific Northwest Ballet and former principal dancer at New York City Ballet, took on the half marathon at almost 50 years old, 10 years after retiring from the stage. He’s since run three of them.

Boal after the Belligham Bay half-marathon in 2016. Photo courtesy PNB.

Boal after the Belligham Bay half-marathon in 2016. Photo courtesy PNB.

He says that his body wouldn’t allow him to dance anymore, even just for fun, and running helped fill the void. “I feel graceful when I run, and I don’t always get to feel that anymore,” he says.

Boal explains that the appeal of the half marathon came from the perfectionism ingrained by ballet. “Running for fun was nice, but I wanted a goal to work toward, to continually improve and measure my progress,” he says.

Asked if he’d recommend marathons to PNB company members, he wasn’t sure if the ballet season was the right time to take it on. “I’d probably recommend swimming at the moment,” he says.

Molnar agrees with him. “The amount of wear and tear and training required, I can’t imagine you could maintain a career as a dancer and train for a marathon,” she says.

Though Arbuckle is freelance, she maintains a busy schedule and said that she was in rehearsal two days after her second marathon. “I actually slipped on a banana peel toward the end of the marathon and got a little banged up, but in rehearsal two days later, I just took it a little easy on kneeling work,” she says.

Waters is undecided on marathon training while performing. “It’s not that it would’ve been bad for me, I just wouldn’t have had time,” she says. After a pause she adds, “But my body feels better than ever now, so who knows?”